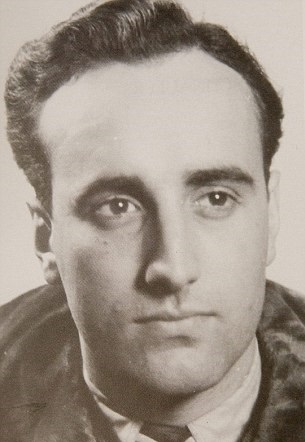

Of noble Russian parentage, Alexander Nikolaievich Prokofiev de Seversky was born in Tbilisi, then part of the Russian Empire (now Georgia) and called Tiflis, June 7, 1894. He entered a military school at age 10. Seversky’s father was one of the first Russian aviators to own an aircraft (a modified Bleriot XI built by Mikheil Grigorashvili) and by the age of 14, when Seversky entered the Imperial Russian Naval Academy, his father had already taught him how to fly. Graduating in 1914 with an engineering degree, Lieutenant Seversky was serving at sea with a destroyer flotilla when World War I began.

Seversky was selected for duty as a naval aviator, transferring to the Military School of Aeronautics at Sebastopol, Crimea. After completing a postgraduate program on aeronautics in 1914–15, he was reassigned as a pilot in the summer of 1915 to an aviation unit in the Baltic Fleet. While stationed in the Gulf of Riga, on his first mission, he attacked a German destroyer but was shot down by enemy anti-aircraft fire before he could drop his bombs. The bombs exploded in the crash, killing his observer and badly wounding Seversky. Doctors amputated his leg below the knee and although he was fitted with an artificial leg, despite his protests, authorities deemed him unfit to return to combat. To prove to his superiors that he could still fly, Seversky appeared unannounced at an air show, but was quickly arrested following his impromptu spirited aerial performance.

Tsar Nicholas II intervened on his behalf and in July 1916, de Seversky returned to combat duty, downing his first enemy aircraft three days later. In February 1917, he assumed command of the 2nd Naval Fighter Detachment, until he was seriously injured in an accident where a horse drawn wagon broke his good leg. After serving in Moscow, as the Chief of Pursuit Aviation, Seversky returned to combat duty. On 14 October 1916, he was forced down in enemy territory but made it back to the safety of his own lines. He went on to fly 57 combat missions, shooting down six German aircraft (his claims for 13 victories would make him Russia’s third-ranking World War I ace although the claims are disputed). Seversky was the leading Russian naval ace in the conflict. For his wartime service, Seversky was awarded the Order of St. George (4th Class); Order of St. Vladimir (4th Class); Order of St. Stanislaus (2nd & 3rd Class); Order of St. Anne (2nd; 3rd; and 4th class).

During the 1917 Revolution, Seversky was stationed in St. Petersburg and remained in uniform at the request of the commander-in-chief of the Baltic Fleet. In March 1918, he was selected as an assistant naval attaché in the Russian Naval Aviation Mission to the United States. Seversky departed via Siberia and while in the U.S., decided to remain there rather than return to a Russia torn apart by the Revolution. Settling in Manhattan, he briefly operated a restaurant.

In 1918, Seversky offered his services to the War Department as a pilot with General Kenly, Chief of the Signal Corps appointing him as a consulting engineer and test pilot assigned to the Buffalo District of aircraft production. After the Armistice, Seversky became an assistant to air power advocate General Billy Mitchell, aiding him in his push to prove air power’s ability to sink battleships. Seversky applied for and received the first patent for air-to-air refueling in 1921. Over the next few years, 364 patent claims were made, among them the first gyroscopically stabilized bombsight, which Seversky developed with Sperry Gyroscope Company in 1923. After joining the Army Air Corps Reserve, Seversky was commissioned a major in 1928.

Using the $50,000 from the sale of his bombsight to the U. S. Government, Seversky founded the Seversky Aero Corporation in 1923. When Seversky left for Europe on a sales tour in the winter of 1938–39, the Board reorganized the operation on October 13, 1939, renamed as Republic Aviation Corporation with Kellett becoming the new president. Seversky sued for redress but while legal actions dragged on, the Board of Directors voted him out of the company he had created.

As World War II approached, Seversky became engrossed in formulating his theories of air warfare. Shortly after the December 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, he wrote Victory Through Air Power, published in April 1942, advocating the strategic use of air bombardment. The best-selling book (No. 1 on the New York Times bestseller list, appearing first in mid-August 1942 and remaining in first place for four weeks) with five million copies sold. The book’s popularity and hard-hitting message led to Walt Disney adapting the book into an animated motion picture (1943) of the same name where Seversky (who also served as the film’s technical consultant) and General Mitchell provided live-action commentary. The Disney animated film received a lukewarm reception at the box office and from critics who felt it was an unusual departure from the standard Disney studio fare, sending out a powerful propaganda message based on an abstract political argument. The influence of both the book and film in wartime, however, was significant, stimulating popular awareness and driving the national debate on strategic air power.

Seversky was one of a number of strategic air advocates whose vision was realized in the 1946 creation of the Strategic Air Command and the development of aircraft such as the Convair B-36 and B-47 Stratojet. Seversky continued to publicize his ideas for innovative aircraft and weaponry, notably the 1964 Ionocraft which was to be a single-man aircraft powered by the ionic wind from a high-voltage discharge. A laboratory demonstration was acknowledged to require 90 watts to lift a two ounce (60 g) model, and no man-carrying version was ever built.

In postwar years, Seversky continued to lecture and write about aviation and the strategic use of air power, following up his landmark treatise with Air Power: Key to Survival (1950) and America: Too Young to Die! (1961).

Seversky died in 1974 at New York’s Memorial Hospital, and was buried in the Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx.

He received the Harmon Trophy in 1939 for advances in aviation. For his work on air power, Seversky received the Medal of Merit in 1945 from President Harry Truman and the Exceptional Service Medal in 1969 in recognition of his service as a special consultant to the Chiefs of Staff of the USAF. In 1970, Seversky was enshrined in the National Aviation Hall of Fame.