Design changes to H2X and later Hawk III in October 1998 resulted in Hawk 4. Initial aircraft (N402GB) first flew 29 September 1999, powered by a Continental piston engine, and made first vertical take-off on 9 December 1999; had flown 120 hours in 200 sorties by early April 2000. In September 2000 company switched certification effort to turbine-powered Hawk 4T (N403GB), which was renamed Hawk 4 at this time following abandonment of piston-engined version; the following October Groen changed its focus to seek government contracts for Hawk 4, slowing certification process for both piston- and turbine-powered versions until it sees market upturn.

GBA analysises and optimises gyroplane rotor blade airfoil performance resulting in a family of natural laminar-flow airfoils for the rotor blades of the Hawk 4 and successor gyroplanes. The airfoil design optimizes the lift/drag relationship for the Hawk rotor system. Initial Hawk models will use aluminum rotor blades with GBA’s proprietary airfoil design, and subsequent models are anticipated to use composite blades with an enhanced GBA proprietary airfoil design that will permit increased operating speeds.

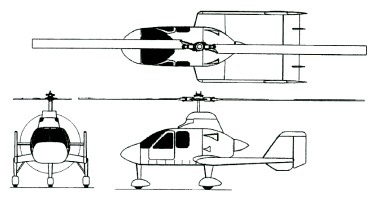

The aircraft features twin tailbooms supported by stub-wings which also house main landing gear, and twin stabilisers and rudders with fixed horizontal tail surface mounted between the vertical tails. A two-blade, semi-rigid aluminium teetering rotor with swashplate has a rotor speed of 270rpm. The collective pitch-controlled rotor head allows vertical take-off (zero ground roll) and enhanced flight performance. Rotor brake is standard. Actuation by pushrods. Patented dual-control stack cyclic flight controls.

The structure had a steel mast and engine mounts; stressed skin aluminium semi-monocoque fuselage, tail unit, hub structure and propeller; composites nose, engine cowling and wingtips; acrylic windscreen and doors; glass fibre nosecone and engine cowling.

The undercarriage is fixed tricycle type with mainwheel tyres 6.00×6; nosewheel 5.00×5, Cleveland hydraulic brakes, and twin safety wheels at rear of tailbooms.

Hawk 4 piston-powered version has air-cooled, six-cylinder Teledyne Continental TSIO-550 rated at 261kW at 2.700rpm; prototype had four-blade MTV propeller but production models will have Hartzell three-blade constant-speed propeller. Engine provides power to rotor for prerotation to provide for short and vertical take-off capability; power to rotor system never engaged during flight.

Fuel capacity is 284 litres in a single tank at the rear of the fuselage and a refuelling point at the top of the fuselage. Oil capacity 11.4 litres.

The pilot and up to three passengers are in an enclosed cabin in two pairs of seats. The rear seats folding to provide baggage space.

The electrical system is 28V DC.

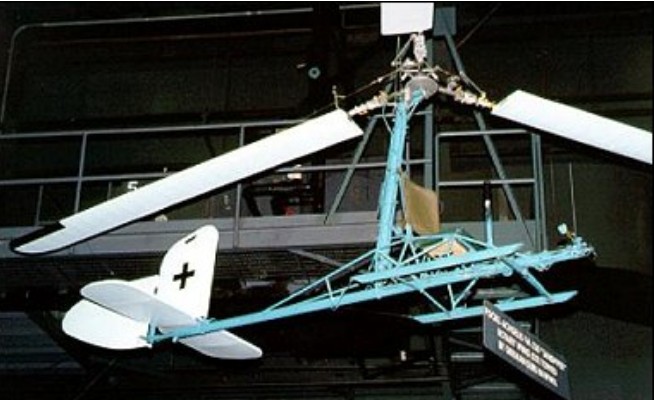

The production prototype for Hawk series was powered by a 134kW Textron Lycoming O-360-A4M flat-four.

The company has a flight test facility at Buckeye, Arizona, where, on 12 July 2000, the prototype Jet Hawk 4T / Hawk 4 made its initial flight. This turbine-engine version is powered by a Rolls-Royce Model 250 420shp turboprop engine driving a three-blade constant-speed propeller, first flown (N403GB) on 12 July 2000. Other changes include addition of underfins and taller landing gear. Two further prototypes under construction.

The Hawk 4T is sold fully assembled with a Rolls-Royce Model 250 B17C gas turbine for $749,000 in 2001. By May 2003, deposits on 148 aircraft had been taken, via 12 dealerships at around US$749.000 (2003). Fractional ownership programme announced July 2001 but later dropped.

The Hawk 4 was an integral part of security during the 2002 Winter Olympic and Paralympic Games. On 28 December 2001, Groen announced contract with Utah Olympic Public Safety Command for lease of Hawk 4, beginning 20 January 2002, for security patrols at Salt Lake International Airport, equipped with video downlink system, Spectrolab SX-5 searchlight and additional radios. The Hawk 4, during its operational period for the Utah Olympic Public Safety Command (UOPSC), was available 24-7, completed 67 missions and accumulated 75 hours of maintenance free flight time.

Hawk H4

Engine: Rolls-Royce 250, 420shp

Rotor diameter: 12.80m

Fuselage length: 7.31m

Overall height: 4.11m

Empty weight: 835kg

Max. take-off weight: 1587kg

Useful load: 960 lb

Fuel capacity: 75 USgal

Max. speed: 238km/h

Cruising speed at 75% power: 212km/h

Max. rate of climb at sea level: 457m/min

Service seiling: 4875m

Take-off run: 8m

Range with max fuel at 75% power: 584km