The town of Colditz in eastern Germany is the home of Oflag IV-C, the most secure prison camp in the Third Reich. Housed in an 11th Century castle, 500 Allied officers – including Sir Douglas Bader and SAS founder David Stirling – had little chance of escape.

The castle walls were more than 6ft thick and prisoners’ cells were built around a central courtyard, its only exit blocked by three sets of heavily guarded gates. There was one guard for every prisoner.

Tunnelling seemed impossible because the castle sat on an outcrop of volcanic rock. Even so, Allied prisoners made 186 escape attempts before the camp was liberated on April 16, 1945. The first of 11 Britons to make a ‘home run’ was former Northern Ireland Secretary Airey Neave, who disguised himself as a German officer and walked out of the camp during a theatrical production through a trap door prisoners built under the stage.

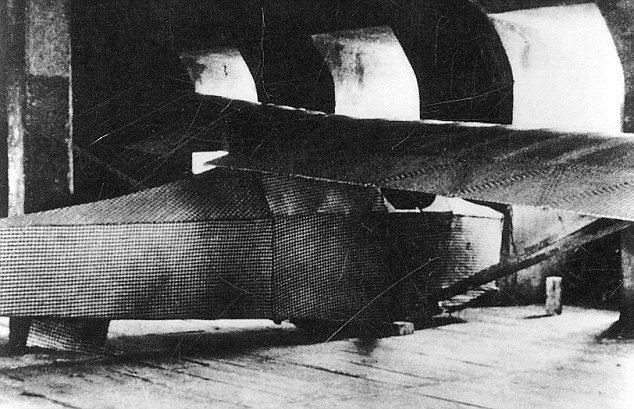

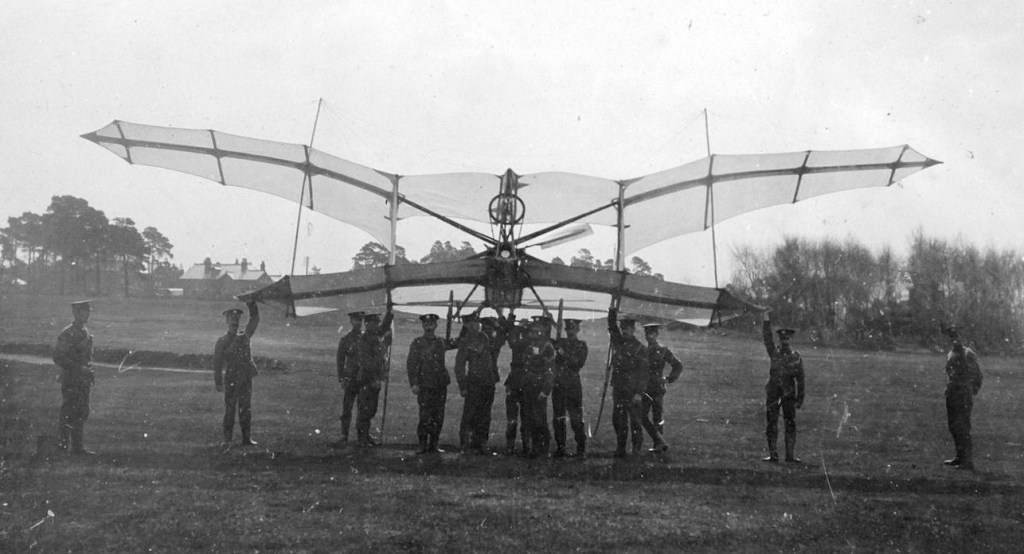

They managed to construct a glider designed by W.Goldfinch, from materials including bedsteads, floorboards, cotton sheets and porridge. Sixteen British prisoners had built the two-man glider behind a false wall in the prison attic, in a space just 20ft by 7ft. Forty more acted as lookouts. ‘Forty guys collected their rations during the period of the project to glue the glider together,’ said Tony Hoskins, the engineer in charge of the reconstruction.

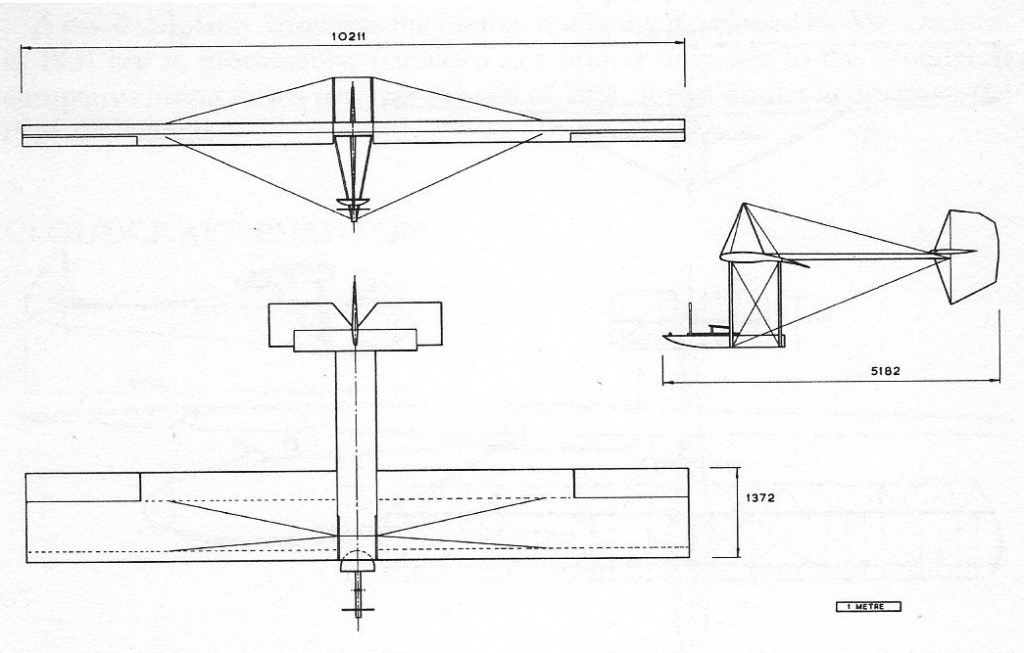

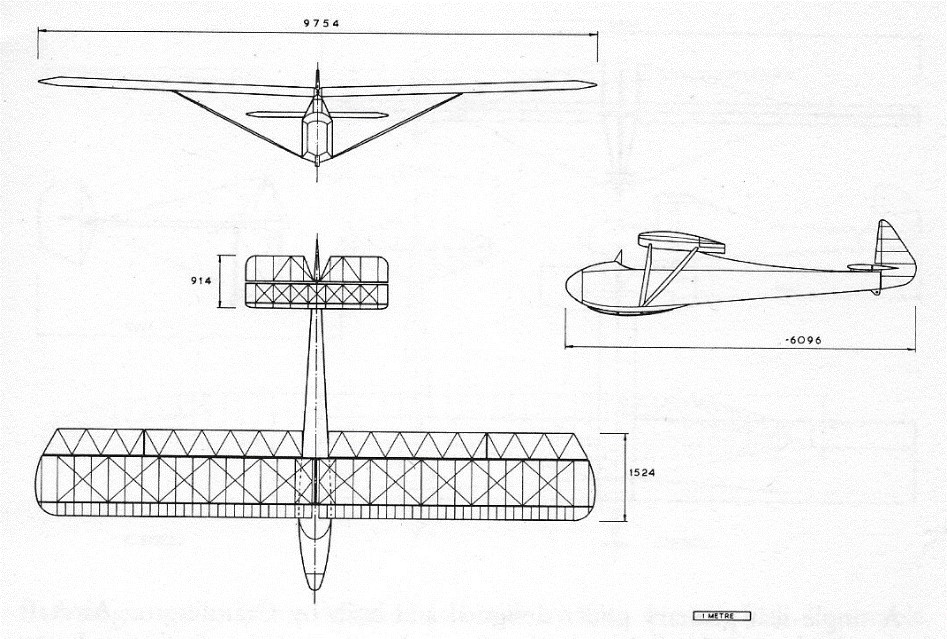

They fashioned tools from bedsteads and iron window bars and made the wing spars from floorboards, the glider skin from cotton sheets and the control wires from electric cable. The finished glider spanned 33ft 9in and was 19ft 7in long.

The prisoners planned to construct a runway on the castle’s sloping roof. The idea was to knock a hole through the roof from their workshop under cover of darkness. They were then going to haul the glider out and attach its wings before launching from the runway by catapulting it with the aid of a bathtub, weighted down with concrete.

The glider, though, was never tested because the castle was liberated by the Americans before the prisoners had a chance to try.

Only one photograph and one crude A4 sketch exists of the glider, which townspeople believe was burnt as firewood.

But engineers and historians have long questioned whether their two-man machine would actually fly. It left the question of could British prisoners have succeeded in their attempt to fly off the roof of the Colditz Castle and make their escape in a glider?

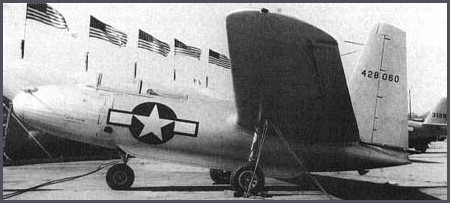

In 2012, a Channel 4 crew created a replica in the attic where it was originally conceived – from similar materials with modern tools. They were able to complete it in two weeks, compared with the ten months it took the prisoners.

The replica glider cost £3,500 in materials, including 27 sheets of pine wood, ten 16ft lengths of beech and 525ft of gingham. It was assembled with 700 panel pins, 300 wooden screws and door and window hinges. The ‘skin’ of the original glider had been starched with a ‘porridge’ made from the prisoners’ rations. The engineers copied the original mixture, which was made from millet seed. The hardest thing for us was that there was no formula for the porridge. They started with 22lb of millet in a big pot and tried every method and consistency until they got it right.

The original glider was built to carry two prisoners, but in 2012 a polystyrene dummy, nicknamed Alex, sat in the cockpit while the aircraft was steered by remote control.

D-Day for the replica Colditz glider came on March 17 2012. The team gathered at 5.45am to assemble the glider on the platform on the apex of the castle roof. The fuselage, tail, rudder and wings, wrapped in a fabric sling for protection, were all lifted individually round the clock tower and on to the roof using a system of ropes.

Amid the sound of chapel bells and rousing cheers from spectators, including the Mayor of Colditz, Matthias Schmiedel, and the German aviation official who signed off the flight, the glider finally rose into the sky at 2.30pm and achieved its first goal – it flew, crossing the River Mulde.

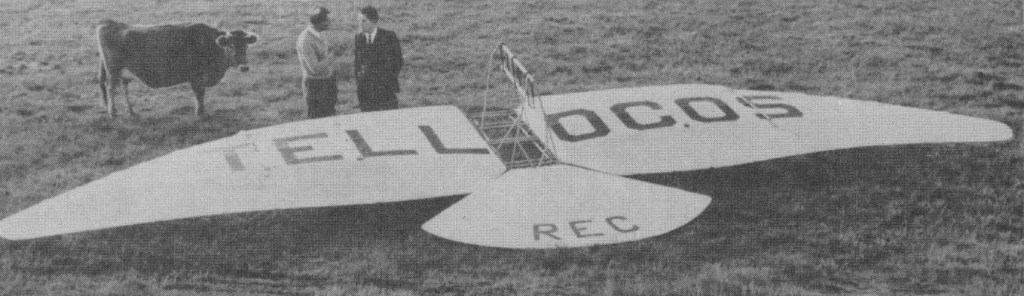

Travelling at 36mph, it then swooped down along the river before turning steeply and crash landing – wing tip first – in the middle of a field after flying 984ft.

‘She came off there like a treat,’ said Pat Willis, 53, who controlled the military-standard radio transmitter. ‘The crash landing was deliberate. I was running out of space so I dumped the glider about 50ft short. There was no way I was going to go through people’s property.’

The flight was monitored on a live video link from the cockpit. ‘We’ve proved that the concept worked,’ said Mr Hoskins. ‘We launched it and it had ample speed as it left the roof. The problem was on arrival. The rudder was fairly ineffective, so when it went to instigate a right-hand turn it was very slow in coming round.

Alexander, the polystyrene dummy, was decapitated.

Wingspan: 9.75 m / 32 ft 0 in

Length: 6.10 m / 20 ft 0 in

Wing areaL 15.05 sq.m / 162 sq.ft

Aspect ratio: 6.4

Wing section: Clark Y-H

Empty weight: 108.86 kg / 240 lb

AUW: 254.02 kg / 560 lb

Wing loading: 16.84 kg/sq.m / 3.45 lb/sq.ft

Max L/D: 12

Stall: 50 kph / 31 mph

Undercarriage: main skid