In 2010 Jimmy Leeward returned Jeannie to Reno with the original 1940s name – ‘The Galloping Ghost”.

In 2010 Jimmy Leeward returned Jeannie to Reno with the original 1940s name – ‘The Galloping Ghost”.

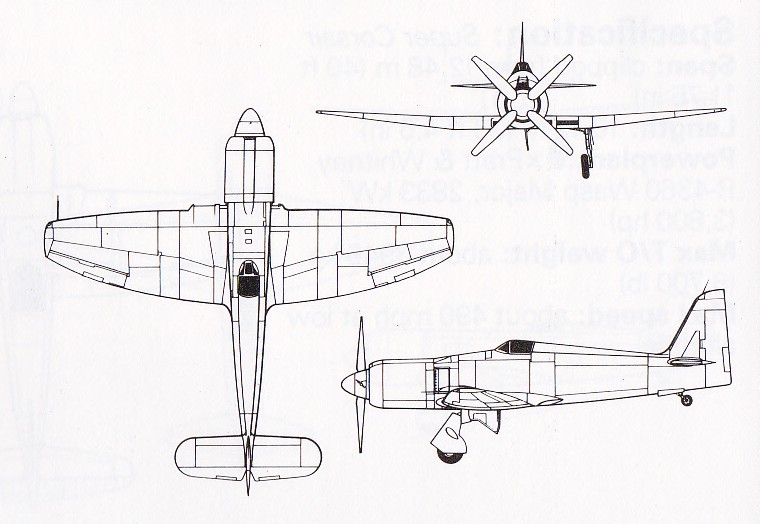

California-based Lloyd Hamilton has long been associated both with the sport of air racing and with the Hawker Sea Fury. Furias was built up from the components of a number of Sea Fury airframes and a 2833-kW (3,800-hp) R-4360 radial and the propeller of a Douglas A-1 Skyraider installed in place of the stock Centaurus engine and propeller. Qualifying at over 400 mph at Reno in 1985, over the years various modifications have been incorporated, including a turtledeck, but victory continues to elude this unique razor-back Fury. Furias is flown in a colour scheme of red with the upper fuselage and the rear portions of the inner flying surfaces in gold.

Furias

Span: slightly less than 11.7 m (38 ft 4.75 in)

Length: about 10.57 m (34 ft 8 in)

Powerplant: 1 x Pratt & Whitney R-4360 Wasp Major, 2833 kW (3,800 hp)

Max TO weight: about 4536 kg (10,000 lb)

Max speed: about 470 mph at low altitude

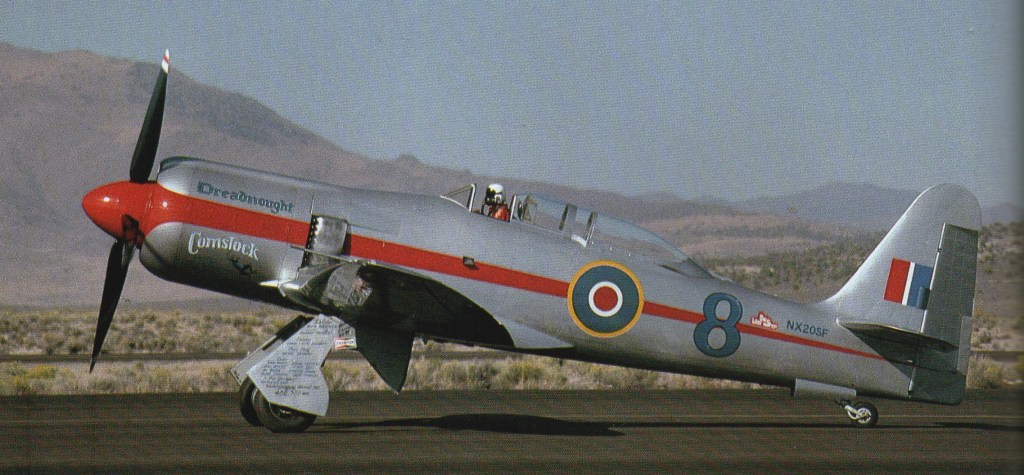

Frank Sanders Racing is responsible for this former Royal Navy Sea Fury T.Mk 20 racer. Dreadnought was prepared at Chino by Frank and his sons Dennis and Brian in 1982/3, and the two-seat aeroplane sported several modifications, the most obvious was the replacement of the original 1849-kW (2,480-hp) Bristol Centaurus with a Pratt & Whitney R-4360 radial. A four-blade propeller was fitted in place of the Sea Fury’s characteristic five-blade unit.

The pilot for the first outing was Neil Anderson. Neil completed the Reno course in Dreadnought at 446.39 mph, breaking the qualifying record and eventually taking first place in the Gold Championship to make this another first-time-out winner in 1983.

Dreadnought

Span: 11.7 m (38 ft 4.75 in)

Length: increased from 10.54 m (34 ft 7 in)

Powerplant: 1 x Pratt & Whitney R-4360-63A Wasp Major, 2833 kW (3,800 hp)

Max TO weight: about 3946 kg (8,700 lb)

Max speed: about 480 mph at low altitude

Mike Brown won the Unlimited Gold Race at Reno on September 17, 2006, at a speed of 453.61 mph in Hawker Sea Fury September Fury. Second was Matt Jackson in Sea Fury Dreadnought.

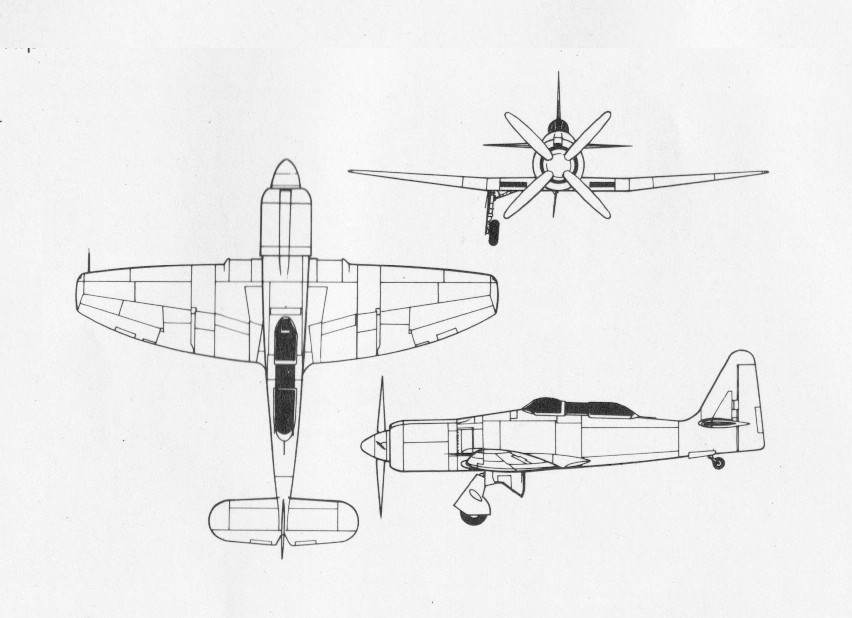

Based on a North American P-51D-30 Mustang airframe, Dago Red was built up by Bill ‘Tiger’ Destefani and Mike Nixon of Vintage V-12s in 1981. On its very first outing at Reno in 1982 the aeroplane took the Unlimited Gold Championship title. Dago Red has a built-up turtlecleck, extensively clipped and faired-in wings and a specially tuned Merlin engine built by Mike Nixon. This runs on 140-octane fuel injected with liquid manganese, with an alcohol/water mix and nitrous oxide introduced further down the induction system.

Dago Red has seen many owners, including Bill Destefani, Alan Preston and David Price. The aeroplane held the world straight-line speed record for piston-engined aircraft at 517.06 mph.

Dago Red

Span: clipped considerably from 11.89 m (37 ft 0.25 in)

Length: 9.83 m (32 ft 3 in)

Powerplant: 1 x Packard VA 650-9 Merlin, about 2610 kW (3,500 hp)

Max TO weight: about 3402 kg (7,500 lb)

Max speed: 517.06 mph at low altitude

Mike Brown won the Unlimited Gold Race at Reno on September 17 2006 at a speed of 453.61 m.p.h. in Hawker Sea Fury September Fury. Second was Matt Jackson in Sea Fury Dreadnought, with Sherman Smoot third in Yak-11 Czech Mate. The other three finishers were all Sea Furies, the only two North American P-51 Ds in the race having retired.

After five days of qualifying, heats, and semi-finals, the 2013 Reno Air Races came to a finish on Sunday with Steve Hinton, Jr., flying the modified P-51 Mustang known as “Voodoo,” winning the Unlimited Class Breitling Gold Race, with a time of 7:59.313 and an average speed of 482.074 MPH.

Hinton beat the second place finisher, Matt Jackson flying “Strega,” by more than seven seconds. Sherman Smoot, flying the Yak 11 “Czech Mate,” finished third.

Hawker Sea Fury N42SF s/n 37721

In 1993 the airframe was rebuilt by Pacific Fighters.

The Curtiss Wright 3350-26 WD engine was overhauled by Precision Air.

Propeller: Hamilton Standard 24E60-305

Designer and builder of Miss Ashley II, Bill Rogers, put a new leading edge on the airplane. Instead of an aluminum leading edge, a new carbon fiber design is being used. He says it is easier to get a good [fast] leading edge that way.

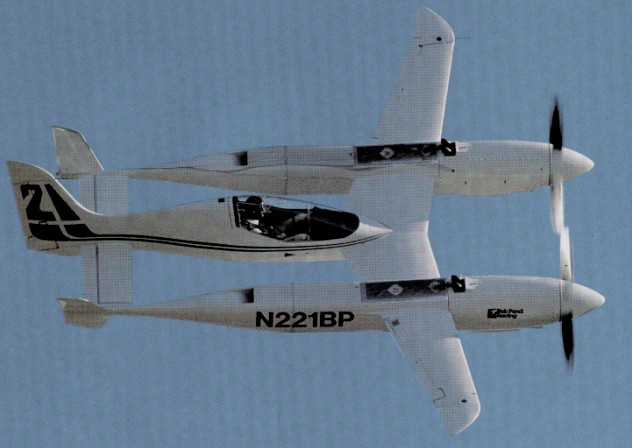

In 1988 Robert Pond (who derives a comfortable income from the manufacture of floor-cleaning products) contracted Burt Rutan’s Mojave, California, Scaled Composites, for the design and production of a prototype new-generation racing plane. Scaled engaged Nissan subsidiary Electramotive, a motorsport engine developer in Vista, California, to provide engines and gearboxes for the airplane. Rutan wanted to keep his pilot away from fuel, oil and hot coolant which meant a fuselage separate from the engine nacelles. The weight of the pilot’s pod is low, since it is supported at both ends and serves no structural purpose other than to hold up the pilot. The interference drag between the wing and the pod is nil. But most important, the pilot is as far away as he can be from the hazards of the powerplants. The airplane’s structure is mostly of graphite composites, often in the form of a sandwich with plastic foam cores. A special epoxy is used for compatibility with the engines’ methanol fuel. Despite its tiny size – 25-foot span and 20-foot length—and advanced materials, the Pond Racer is a dense little airplane, weighing 4,500 pounds ready to fly. Its useful load is only 650 pounds.

Liquid-cooled, with a single overhead cam, two valves per cylinder, and 3.2-liter (200-cubic-inch) displacement, the Electramotive VG30 engines are based on the Nissan V-6 block used in the 300ZX and Maxima automobiles. Though their blocks are very compact, the engines use up a lot of space once the turbochargers and radiators and associated ducting are included (in fact, the complete installed powerplant weighs around 700 pounds versus 350 for the basic engine). They are packed incredibly tightly into the two-foot-diameter, five-foot-long nacelles. The engines are mounted solidly to the airframe and the cowling skins are a load-bearing part of the engine mount, permitting the gap between spinner and cowling to be little more than a knife-slit.

More than a year was spent developing a gearbox to bring the engine’s 8,000-rpm operating speed down to a propeller-friendly 2,000.

The engines are electronically controlled. There are manual backups, but normally the throttle and prop controls move potentiometers, whose signals arrive, digitized, at each engine’s two Intel microcontroller chips along with temperature and pressure data from almost two dozen other sources. The microcontrollers consult schedules containing the desired boost and the duration and timing for the spark and injection, and adjust those parameters for each power stroke.

At the same time, airframe and powerplant data are recorded every two seconds, and can be dumped at the end of each flight to a computer and instantly displayed in graphical form. Technicians can then use the data drawn from each run to modify the laws governing engine operation until the optimum is achieved.

To deliver 1,000 hp, the engines must be boosted to 110 in. Hg and turn at 8,000 rpm. They must run continuously at that setting for the 15 minutes of a race, although they never gave more than about 600hp.

On March 22, 1991, the first flight was described as a “no-brainer”. It took several flights to get the engines working well at moderate power, and even late in August they were still chronically misfiring and undergoing constant readjustment. One source of difficulty is that the engine control computers don’t monitor one variable important to airplanes though not to race cars: air density. With a wing loading of over 70 psf, touchdown is at a hot 120 knots.

The original intention had been to remove some or all of the angled “butterflies” at the tips of the horizontal stabilizer after flight-test demonstrated sufficient directional stability. Now they may be moved to a horizontal position instead, since the airplane has so little static margin that it requires no trimming between 140 and 250 knots.

A major source of trouble during testing has been the methanol fuel. Not a petroleum product, methanol, like alcohol, is derived from plant fermentation. It has about half the specific impulse of gasoline, which means that twice as much of it must be burned to produce a given amount of power. But it also burns over a far wider range of mixtures, so that engine cooling can be supplemented simply by pumping a lot of excess methanol through the engine. What doesn’t burn in the cylinders emerges from the exhaust pipes as a roaring plume of flame familiar to drag-race buffs. Methanol also doesn’t detonate, and that is what allows it to run at the astronomical levels of boost necessary to pull 1,000 hp out of an engine having fewer cubic inches than that of a Cessna 152.

Methanol has very unfriendly relations with many materials. “It eats us alive,” Dick Rutan says. After repeated episodes of corrosion and oil contamination, it became standard operating procedure to drain the fuel systems after each flight and refill them with aviation gasoline in order to protect components from the methanol.

Even if Burt Rutan scored a bull’s-eye in flying qualities, there are still other major uncertainties waiting to be resolved. One is the reliability of the engines while being operated continuously at 1,000 hp. Another is handling qualities at top speed; because the engines can’t be opened up, the Racer has not yet been flown above 333 KIAS (357 knots true airspeed). Yet another unknown is the efficiency of the propellers. Four-blade and 80 inches in diameter, they are King Air props modified by Hartzell to specifications developed by John Roncz, a longtime consultant of Rutan’s who also designed the wing and tail airfoils for the Racer. Their knife-thin tips are designed to run at 98 percent of the speed of sound—not a regime in which propellers are routinely used.

The other question mark is airframe drag. Although the Racer is small, it is complex in shape, with many intersections and much internal cooling flow whose drag is difficult to estimate. At 460 knots, air will slam into it like cinder blocks, with a force of 600 pounds per square foot. At that speed a small surplus of drag could mean the difference between success and failure for the whole project.

Its bulky fuel load notwithstanding, the Pond Racer turned out to be a tiny airplane only 20 feet long, with a wing span of slightly more than 25 feet. It weighs 4,000 pounds when fully fueled. Scaled Composites, Rutan’s company in Mojave, Calif., finished the racer’s airframe in June 1989, but the engines and gearboxes took another year and a half to be completed. During that time the Rare Bear pushed the official speed record to 528 mph one mph faster than Rutan’s hoped for top speed.

At Reno 1991, a connecting rod punched through the left engine’s oil pan, dumping lubricant on the hot exhaust pipes and causing a fire. Race pilot Rick Brickert triggered the Pond Racer’s Halon fire extinguishing system, which smothered the blaze, then flew the craft to a one engine landing. After Reno, the racer was transferred from Mojave to Pond’s home airport at Palm Springs, Calif., to await further development.

N221BP appeared at Reno in 1991-93, qualified at 400mph.

Destroyed in a forced landing crash in 9/14/93, killing pilot Rick Brickert.

Engines: 2 x Electromotive-Nissan VG-30 GTP, 600 hp

Wingspan: 25’5″

Length: 20’0″

Useful load: 640 lb

Designed by Mario Castoldi over three years from 1931 to 1933, it was hoped this plane would enter (and win) the Schneider Trophy race of 1931 but the plane could not be ready in time for that contest (the winner was the British Supermarine S.6B).

First flown in June 1931, the MC.72 was a single-seat twin-float seaplane. The unique engine was effectively two in tandem driving separate (counter-rotating) propellors.

In late 1927, Italian Mario de Bernardi upped the world absolute speed record mark to 298 mph with a Macchi M-52 seaplane developed from the M-39 in which he had won the 1926 Schneider Race. He soon raised the mark to 318 mph with the same airplane.

Problems with the Fiat 24 cylinder engine hp prevented it taking part in the Schneider seaplane contests, but Francesco Agello boosted the 3 km speed record with it to 423.57 mph 10 April 1933 and then 100 km speed record to 390.8 mph. The Coupe de Vitesse Louis Bleriot record of 30 min was raised to 384.86 mph. A world speed record was established on October 23, 1934 at 440.67 mph / 709 km/h. This world speed record lasted for five years – but as a record for a piston-engine seaplane it has never been broken (likely because development of racing seaplanes essentially came to an end with the end of the Schneider Trophy contest).

The Schneider Trophy never experienced any casualties during competition, but several pilots were killed training for the races. Italy had five casualties: Vittorio Centurione in 1926 in a Macchi M-39; Giuseppe Motta in 1929 in a Macchi M-67; Tomasso Dal Molin in 1930 in a Savoia S.65; Giovani Monti and Stanislao Bellini in 1931 in a Macchi MC-72.

As a result of three consecutive victories for the British, the Schneider races were over.

Engine (1934): Fiat AS.6 24 cyl., 2300 hp

Engine (1934): Fiat AS.6 24 cyl., 2500 hp

Engine (1934): Fiat AS.6 24 cyl., 2800 hp

Prop: Twin CR

Engine: 2 x Fiat A.S.6, 2280kW

Take-Off Weight: 2907 kg / 6409 lb

Empty Weight: 2500 kg / 5512 lb

Wingspan: 9.5 m / 31 ft 2 in

Length: 8.2 m / 26 ft 11 in

Height: 3.3 m / 10 ft 10 in

Max. Speed: 702 km/h / 436 mph

Crew: 1