The Bell ‘Pogo’ rocket belt two man platform.

The Bell ‘Pogo’ rocket belt two man platform.

Bell Aerosystems Rocket Belts. These strap on devices had a pair of vectorable nozzles controlled by handlebars and enabled the wearer to be thrust over 15 m (50 ft). The only practical application of the Rocket Belt has been as a gimmick in a James Bond movie. Developed versions of the device have been used by NASA astronauts for spacewalking.

Neat and potentially useful, the rocket belt has proved difficult to control with the finesse necessary for everyday use by non experts.

In the 1960s Bell’s Rocket belt made its public debut. The hydrogen peroxide rocket belt was compact, and also difficult to fly. The fuel is extremely pricey and it runs out so quickly that you’re limited to about 30 seconds of flight.

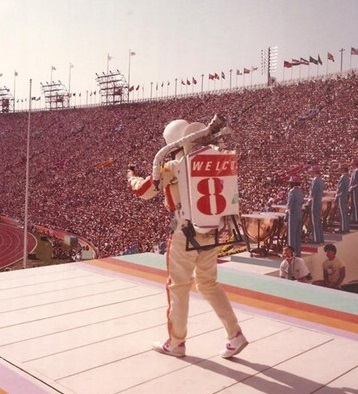

The Jet Belt displayed at the 1984 Olympics opening ceremony in Los Angeles.

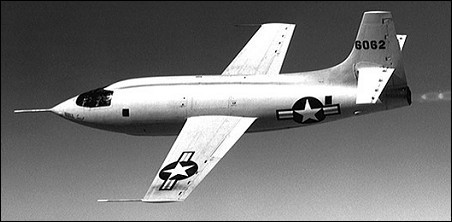

Two X-2s were built by Bell Aircraft at their Niagara Falls, New York, facility. The airframes were composed primarily of stainless steel and “K-Monel,” an advanced lightweight heat-resistant stainless steel alloy swept wings.

The powerplant comprised a 15,500 lb (6804 kg) thrust throttable Curtiss-Wright XLR-25-CW-1 liquid propellant rocket.

The jettisonable cockpit can be separated from the fuselage in an emergency by an explosive charge, a ribbon-type parachute lowering the complete cockpit to a lower altitude at which the pilot can bale put.

The first X-2 was dropped into Lake Ontario on 12 May 1953 following an explosion and fire that also caused extensive damage to the EB-50A launch aircraft.

A leather gasket made by the Ulmer Company, when saturates with liquid oxygen, was so unstable that a shock of and magnitude caused the gasket to blow. A number of accidents occurred involving the X-1-3, X-1A, X-1D, and X-2, before the malfunctioning gasket was identified and a fix made.

The second aeroplane made the type’s first powered flight on 18 Novernber 1955, and recorded an altitude of 126,000 ft (38,465 m) as well as a speed of Mach 3.2 (2,094 mph; 3,370 km/h), the latter being recorded during the type’s fatal last flight on 27 Septernber 1956. This remained the highest speed at which man had flown until 1961. The aircraft experienced “inertia coupling” resulting in complete loss of control—pilot Milburn Apt was killed in the accident. No examples of the X-2 survive.

Dick Day warned his air force associates not to push ahead so fast with the X-2, piloted by Ivan Kinchloe, Frank ‘Pete’ Everest, and Milburn G. Apt. Data from their work was confirming evidence from NACA wind tunnel tests that the X-2 would experience ‘rapidly deteriorating directional and lateral (roll) stability near Mach 4’. On 25 April 1956, the X-2 broke the sound barrier for the first time. Less than a month later, it flew past Mach 2. By mid-summer it was pushing Mach 3. When Mel Apt took the X-2 up on 27 September 1956, for his very first flight in the aircraft, his flight plan called for ‘the optimum maximum energy flight path,’ one that would rocket him past Mach 3 – and into roll coupling. The fatal crash happened just as Dick Day thought it might. At 65,000ft and a speed of Mach 3.2, Apt lost control of the X-2 due to roll coupling and became unconscious. By the time he came to it was too late. He died instantly when the plane hit the desert floor.

The two X-2s achieved 20 flights in total between 1952 and 1956.

Engine: 1 x Curtiss-Wright XLR25-CW-1 rocket engine, 6804kg

Wingspan: 9.75 m / 31 ft 12 in

Length: 13.41 m / 43 ft 12 in

Height: 4.11 m / 13 ft 6 in

Max. speed: M3.2 (2,094 mph; 3,370 km/h).

Ceiling: 38405 m / 126,000 ft / 38,465 m

Crew: 1

Initially designated the XS-1, (the S, which stood for Supersonic, was dropped early in the program), the X-1 was the first aircraft given an “X” designation, and became the first aircraft to exceed the speed of sound in controlled level flight on 14 October 1947. Developed jointly by the USAF, Bell and NACA, the type reached Mach 1.015 at approximately 45,000 feet in the hands of Captain ‘Chuck’ Yeager. The type was planned specifically for investigation into transonic and supersonic flight, and was based on a cylinderical fuselage that accommodated the 6000 lb (2722kg) thrust Reaction Motors E6000-C4 rocket motor and the tanks for its liquid propellants. The flying surfaces were straight but thin, and the first X-1 air launch of the X 1 was made on 19 January 1946, but powered flights were not attempted until 9 December 1946 after an air drop from a Boeing B-29 motherplane, using the second prototype. The third was destroyed at Edwards AFB during flight fuelling operations.

Supersonic flight was achieved by Captain Charles ‘Chuck’ Yeager on 14 October 1947. The speed reached by the X 1 on that occasion was 670 mph (1,078 kph) at a height of 42,000 ft (12,800 m), and therefore equivalent to a Mach number of 1.015.

On 5 January 1949, piloted by Chuck Yeager, the X-1 took-off from the ground under its own power. After a take-off run of 2300 ft it climbed at 13,000 fpm.

The three X-ls were followed by the second generation X-1s were designed to double the speed of sound and set altitude records in excess of 90,000 feet. Only the X-1A and X-1B were actually built—the X-1C, which was designed to test high-speed armaments, was cancelled before completion.

The X-1A had a longer fuselage for greater fuel capacity, a revised cockpit canopy, and turbopumps replacing the previously pressurised nitrogen fuel system: the X-1A reached a speed of Mach 2.435 and an altitude of more than 90,000 ft (27430m) on 4 June 1954.

In 1955 this aircraft was given new wing panels, but was destroyed before its first flight in this configuration. The X-1A was destroyed after it was jettisoned following an inflight explosion over Edwards AFB on 8 August 1955.

The X-1A and X-1B differed by having a stepped canopy, a 4 ft 7 in longer fuselage, and a turbo-pump fuel system. The X-1A attained Mach 2.5 (1650 mph) at 70,000 ft on 16 December 1953. The X-1B was used for thermal research,

The X-1D was destroyed during what was to be its first powered flight in August 1951 after being jettisoned from its B-50 carrier-plane, following an explosion.

On 8 August 1955, just an instant before Joe Walker was to be dropped in the X-1A, an explosion within its rocket engine rocked the B-29. Walker immediately scrambled up and out of the X-1A and into the bomb bay of the mothership. The X-1A was to damaged to fly, and the B-29 could not risk landing with it still hooked to the underside. B-29 pilot Stan Butchart had no choice but to jettison the X-1A into the desert. The machine exploded on impact, ending the X-1A programme. It was learned later that a gasket blew when Walker threw the switch to pressurise the liquid oxygen and water alcohol in the X-1A’s fuel tanks.

A leather gasket made by the Ulmer Company, when saturates with liquid oxygen, was so unstable that a shock of and magnitude caused the gasket to blow. A number of accidents occurred involving the X-1-3, X-1A, X-1D, and X-2, before the malfunctioning gasket was identified and a fix made.

Neil Armstrong and Stan Butchart air-dropped pilot Jim McKay in the X-1B for a zoom to 55,000ft, one that did not slow enough at the top to check out reaction controls. Immediately after McKay’s flight, mechanics found irreparable cracks in the rocket motor’s liquid oxygen tank (by then the X-1B was about 10 years old), ending the entire X-1B program.

Despite the loss of the third X-1 and the X-1D, a requirement still existed for a higher performance X-1 so that the NACA could continue high-speed research. To satisfy this requirement, the second X-1 was almost completely rebuilt and redesignated the X-1E. Significant modifications included an updated knife-edge windscreen canopy, ultra-thin wings (4 percent thickness/chord ratio), turbo-driven fuel pumps, and a rocket assisted ejection seat.

With these aircraft, a speed of 1,650 mph (2655 km/h) at 70,000 ft (21,325 m) and altitudes of up to 90,000 ft (27,425 m) were attained in 1953-54.

The maximum altitude achieved by the X-1E was over 75,000 feet, and the top speed was Mach 2.24 (1,450 mph). During its test series, the X-1E demonstrated that the thin wing section was technically feasible for use on supersonic aircraft. An improved Reaction Motors XLR11, using a low-pressure turbopump, was also validated during X-1E test flights.

The aircraft was retired from service in November 1956 after 26 flights, and is now on permanent display in front of the NASA Dryden Flight Research Center.

The first X-1 is on permanent display in the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC. The third X-1 was destroyed on 9 November 1951 at Edwards AFB, California.

A total of 156 flights were made with the X-1, 21 with the X-1A, 27 with the X-1B, one with the X-1D and 26 with the X-1E.

X-1

Powered by: One Reaction Motors XLR-11-RM 5 four-chamber bi-fuel (alcohol and liquid oxygen) rocket, maximum of 6,000 lb (2722 kg) st for 2.5 min.

Wing span: 28 ft 0 in (8.53 m).

Length: 31 ft 0 in (9.45m).

Height: 10 ft 8 in (3.25m).

Empty Weight: 8,100lbs (3,674kg)

Gross wt: 13400 lb (6,078 kg).

Max speed: 1000 mph (l609 kph) at 60,000 ft (18,2 90 m).

Rate of climb: 28.000 ft (8,534 m)/min.

Ceiling: 22250 m / 73000 ft

Accommodation: Crew of 1.

No built: 3

Operated: 1946-51

No of flights: 157

X-1A

Power: 6,000 lb thrust Reaction Motors XLR-11-RMS rocket

Span: 28 ft

Weight: 16,000 lb

Speed: 1650 mph.

Ceiling: 90,000 ft.

Full power endurance: 4.2 minutes

No built: 1

Operated: 1953-55

No of flights: 25

X-1B

Endurance: 4.2 min

Empty weight: 7000 lb

Loaded weight: 18,000 lb

Wingspan: 28 ft

Length: 35 ft 7 in

Height: 10 ft 8 in

No built: 1

Operated: 1954-58

No of flights: 27

X-1D

No built:

Operated: 1951

No of flights: 1

X-1E

No built: 1

Operated: 1955-58

No of flights: 26

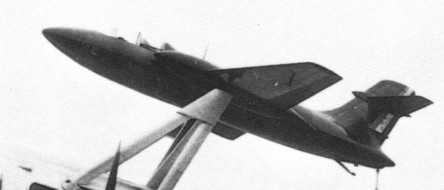

In August, 1944, that the idea of “Natter” (German for Viper) was conceived and four designers, Heinkel, Junkers, Messerschmitt and Bachem, were directed to submit plans. Diplomeur Ingenieur Erich Bachem who made his first appearance with his submission of the BP(Bachem Projekt)20 Natter (Adder). The BP-20 was envisioned as a small lightweight expendable interceptor, capable of destroying any enemy bomber using the least possible weapon expenditure. Dr. Bachem’s design was chosen and in November of that year Natter BP-20 was flown for the first time. Smaller than the Me-163 (span, 13 feet; length, 20 feet, 6 inches) and simpler to build (wooden airframe required only 600 man hours) it looks more like a mock-up than a full-fledged fighter. Because of the short take-off area required it was well suited to close defense of vital targets and pilots required very little training. Launched from a nearly vertical ramp, powered by a Walter rocket unit similar to that used in the Me-163, the initial rate of climb was calculated at 37,000 feet per minute, its top speed at more than 600 miles per hour. A controlled missile until within a mile of its target, the pilot then takes over, jettisons the nose cone exposing 24 Fohn 7.3 caliber rockets which are fired in one salvo. Protected by exceptionally heavy cockpit armor and presenting a small head-on target, the pilot is virtually invulnerable to enemy fire. His principal danger is in take-off and descent. Going into a dive after two minutes or less in the air he bails out and a section of the fuselage containing the rocket unit likewise descends by parachute. It was the first vertical-takeoff fighter ever built and certainly the first where the pilot was expected to bail out on every mission.

That project had its origin in a proposal in 1939 by rocket engineer Dr. Werner von Braun. This proposal was rejected as unworkable by the Reichluftfahrtministerium (RLM-German Air Ministry) but found an enthusiastic supporter in Bachem who tried, and failed, to generate interest in several different proposals for a rocket interceptor along the lines suggested by von Braun.

The airframe was comparatively crude, largely of wood construction and was to be built without the use of gluing presses or complex jigs. Most parts could be made in small woodworking shops through Germany, without interfering with the existing needs of the aircraft industry. According to Bachem, only 600 man-hours would be required for the production of one airframe, excluding the rocket motor, which was relatively simple to manufacture when compared to a sophisticated turbojet. This motor was the same basic engine used in the Me-163 Komet interceptor, a Walter 109-509A-1 that used the reaction between two chemicals, T-Stoff (a highly caustic solution of concentrated hydrogen peroxide and a stabilizer) and C-Stoff (a mixture of hydrazine hydrate, methanol alcohol, and water) to provide 3,740 lb (1,700 kg) of thrust. Extra power for lift-off was generated by four 1,102 lb thrust solid-fuel rocket boosters bolted to the rear fuselage giving a combined thrust of 4,800 kgf (47 kN or 10,600 lbf) for 10 seconds.

The short, untapered, stubby wings had no ailerons, lateral control being exercised by differential use of the elevators mounted on a cross-shaped tail augmented by guidel vanes positioned in the exhaust plume of the main rocket. The cockpit was armored and armament consisted of 24 unguided Henschel Hs 217 Föhn 73 mm rockets mounted in tubes in the nose of the aircraft and covered by a nose cone.

The cockpit was equipped with only basic instruments, the instrument panel actually serving as the pilot’s frontal armour. The pilot was protected by armour on each side of the seat, and a rear armoured bulkhead at his back separated the cockpit from the fuel tanks, which contained 6gal of a hydrogen peroxide and oxyquinoline stabiliser solution and 41.8gal of 30 per cent hydrazine hydrate solution in methanol.

In operation, the Natter would be launched from a 79 ft (24 meter) tower. Guide rails would stabilize the wingtips and lower tailfin until the tower was cleared. (Towards the end of the war, as steel became scarce, the tower was replaced with a simple 29 ft [9 meter] wooden pole with a pair of shortened launch rails bolted to it. There was the need for a solid concrete foundation into which the gantry could be secured, though the wood pole version could be quickly dismantled and removed from a mounting set into such a base.) Controls would be locked during launch. About 10 seconds after launch, the solid-fuel boosters would burn out and be detached by explosive bolts and the controls would become operational. The aircraft’s autopilot would be controlled from the ground by radio; the pilot could assume manual control at any time. The Natter would accelerate upward with a proposed climb rate of 37, 400 ft (11,563 meters) per minute until it reached the altitude of the Allied bomber formations which could range from 20,000 ft to 30,000 ft (6,250 meters to 9,375 meters). The pilot would then take control of the Natter, steer it in close, jettison the nose cone, and fire all 24 of the rockets simultaneously at the bomber. The rocket fuel would be exhausted by now and the pilot was to glide downward to about 4,500 ft(1,400 meters). He would then release his seat harness and fire a ring of explosive bolts to blow off the entire nose section. A parachute would simultaneously deploy from the rear fuselage and the sudden deceleration literally throw the pilot from his seat. The pilot would activate his own parachute after waiting a safe interval to clear the bits of falling Natter. Ground crews recovered the Walter motor to use again but the airframe was now scrap. It was also envisioned that the Natter could be used on the remaining surface fleet with an air defense capability previously denied to ships.

Bachem now pulled strings to get his proposal accepted. The strings that he pulled belonged to Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler, head of the Shutzstaffel (SS-Protective Staff). Himmler saw the possibility of establishing a fleet of aircraft beyond the control of the Luftwaffe and the RLM and signed an order for 150 of Bachem’s machines using SS funds. Alarmed, the RLM now approved Bachem’s design and placed their own order for 50 of the aircraft under the designation Ba-349 Natter (Adder).

With orders from both the Luftwaffe and the SS Führungshauptamt (Planning Office), Bachem set up a factory to design and build his dream at Waldsee in the Schwarzwald (Black Forest) about 25 miles (40 km) from the Bodensee (Lake Constance). Wind-tunnel models which were built early in the program were shipped off for testing and the only results returned to the Bachem designers were that it would be satisfactory up to speeds of about 685 mph (1,102 km/h).

An initial series of 50 Natters was built within three months of the launching of the project, and unpowered gliding trials began in November 1944.

The first successful pilotless launch was accomplished on December 22, 1944, with a dummy in the cockpit. A Heinkel He-111 bomber carried one to 18,000 ft (549 meters) and released it. The pilot found the aircraft easy to control. At 3,200 ft (1000 meters), he fired the explosive bolts and the escape sequence worked as designed.

A powered vertical launch failed on December 18 because of faulty ground equipment design. On December 22, the aircraft made its first successful launch with the solid fuel boosters only because the Walter motor was not ready. Ten more successful launches followed during the next several months. Early in 1945, the Walter engine arrived and the Natter launched successfully with a complete propulsion system on February 25, 1945, carrying a dummy pilot. The launch proved that the complete flight profile was workable. All went according to plan, including recovery of the pilot dummy and Walter rocket motor.

Although Bachem wanted to conduct more pilotless tests, he was ordered to begin full power piloted trials immediately. On February 28, 1945, a volunteer, Oberleutnant Lothar Siebert, attempted the first manned, full power Natter launch. However, the cockpit canopy detached itself at an altitude of 1,650 ft because of improper locking. Siebert was knocked unconscious as the Natter continued to climb to 4,800ft before nosing down and crashing, with fatal consequences. More pilots volunteered to fly and the Bachem team launched three flights in March.

Manned flights continued, seven of them, but only 36 of the 200 Natters ordered were completed.

Altogether 25 Natters actually flew, though only seven of the flights were piloted, in April 1945 ten Natters were set up at Kirchheim near Stuttgart to await a chance to intercept Allied bombers. However, Allied tanks arrived at the launching site before the bombers appeared, and the Natters were destroyed on their ramps to prevent their capture.

French tanks advanced into Waldsee on April 1945 and a great number of spare parts from the Bachem factory were captured. Only a few days before the French arrived, fifteen rocket engines destined for Nattern had been thrown into Lake Waldsee to prevent their capture. The secret was not well kept however and all were later recovered.

A B model Natter, with revised armament and an auxiliary cruise chamber in the engine to increase powered endurance from 2.23min to 4.36min, was in the works at the end of the war. Three Ba 349Bs were built before VE Day, but only one was test flown.

Only two authentic Nattern survive. One is at the Deutsches Museum in München (Munich), restored in the colors and markings of one of the unmanned test aircraft. The Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington DC has the other Natter which was captured by U. S. forces at the war’s end and shipped it to Freeman Field, Indiana, for analysis. The captured equipment number T2-1 was assigned to the Natter and the US Air Force transferred it to the National Air Museum (now NASM) on May 1, 1949.

Ba 349

Engine: One Walter HWK 509A rocket + 4 solid rocket boosters, 16.7 kN (10,600 lbf)

Launch weight: 800 kg (1940 lb) (empty), 2,232 kg (4,920 lb) (full load)

Length: 6.02 m (19 ft 9 in)

Height: 7 ft 4.5 in

Wing span: 3.60 m (11 ft 10 in)

Wing area: 51.6 sq.ft

Speed: 1,000 km/h (620 mph)

Range: 6 min of flight

Flying altitude: 14,000 m (46,000 ft)

Warhead: 24x 73 mm Hs 217 Föhn rockets or 33x 55 mm R4M rockets

Ba 349A

Powerplant: one 1700 kg (3,748 1b) thrust Walter 109 509A 2 liquid fuel rocket motor (of 70 sec power duration) and four 1200 kg (2,646 lb) thrust Schmidding 109 533 solid fuel jettisonable booster rockets (of 10 sec power duration).

Max speed: 800 km/h (497 mph) at SL / 560 mph at 16,400ft

Service ceiling: 14000 m (45,930 ft)

Initial ROC: 11140 m (36,550 ft)/min.

Radius of action: 40 km (24.8 miles).

Launch Weight: 2200 kg (4,850 lb).

Wing span: 3.60 m (11 ft 9.75 in)

Length: 6.10 m (20 ft 0 in)

Wing area: 2.75 sq.m (29.6 sq.ft)

Armament: 24 Fohn 7.3 cm (2.87 in) unguided rocket projectiles in nose.

Ba 349B-1

Engine: One 4,409 lb (2,000 kg) st Walter HWK 509C 1 bi fuel rocket motor, plus (for take off) four 1,102 lb(500kg) or two 2 205 lb (1,000 kg) Solid fuel rockets.

Wing span: 13 ft 1.5 in (4.00m).

Length: 19 ft 9in (6.02 m).

Wing area: 50.59 sq.ft (4.70sq.m)

Gross weight: 4,920 lb (2,232 kg).

Max endurance: approx 4 min.

Crew: 1

Initial ROC: over 37,000 ft (11,280 m)/min.

Max speed: 620 mph (1000 kph) at 16,400 ft (5,000 m).

The Armstrong Siddeley Screamer was a liquid oxygen (LOX) / methanol rocket engine intended to power the Avro 720 manned interceptor aircraft (Avro’s competitor to the Saunders-Roe SR.53 for a rocket-powered interceptor). Thrust was variable, up to a maximum of 8,000 lbf.

Work on the Screamer started in 1946, with the first static test at Armstrong Siddeley’s rocket plant at Ansty in March 1954. The programme was cancelled, as was the Avro 720, before flight testing.

In 1951, a Gloster Meteor F.8 was experimentally fitted with a Screamer mounted below the fuselage.

The Screamer project was cancelled in March 1956, at a reported total cost of £ 650,000.

The Armstrong Siddeley ASSn. Snarler was a small rocket engine used for combined-power experiments with an early turbojet engine and was the first British liquid-fuelled rocket engine to fly. The Armstrong Siddeley’s used liquid oxygen (75 imperial gallons / 340 lt) and water-methanol (120 imperial gallons / 550 lt). The rocket engine is described as having a dry weight of 215 lbf (960 N) thrust of 2,000 lbf (8.9 kN) and a specific fuel consumption of 20 (lb/h)/lbf thrust. Work began in 1947 and the final configuration was first tested on 29 March 1950.

The prototype of the Hawker P.1040 Sea Hawk, VP 401, had a Snarler rocket of 2,000 lbf (8.9 kN) thrust added in its tail. The Rolls-Royce Nene turbojet, of 5,200 lbf thrust, had a split tailpipe which exhausted either side of the fuselage. The combination was termed the Hawker P.1072. This gave approximately 50% greater thrust, although at a fuel consumption of around 20×. It was first used in flight on 20 November 1950, by Hawker’s test pilot Trevor “Wimpy” Wade. Half a dozen flights were made using the rocket motor before a minor explosion damaged the aircraft. Although methanol was used in the P.1072, jet fuel could be used for the Snarler. It was decided that reheat was a more practical proposition for boosting jet thrust than rockets.

An unusual feature of the engine was that the turbopump was externally driven, by a drive from the gearbox of the P.1072’s turbojet engine.

Variants:

ASSn.1 Snarler

The prototype and test engines, (given the Ministry of Supply designation ASSn.).

Aerospace General Corp announced their Mini Copter with an optional landing skid. Two small rocket motors powered the Mini Copter, converting hydrogen peroxide fuel into superheated steam which was released through rotor tip nozzles, providing equivalent to a 90 hp engine. Fuel was carried in two tanks each side of the pilot. The entire machine fitted into a cylindrical container no larger than a jet fighter’s droptank. The Mini-Copter was first flown in 1973.

The Mini-Copter was intended originally for air-dropping to a pilot who had been forced down behind enemy lines or in terrain unsuited to conventional rescue. It was evaluated by the US Army in an Individual Tactical Air Vehicle (ITAV) role in three configurations:

Planned shortly after the end of WW2, as a jet powered NC.270 bomber with two Rolls-Royce Nene turbojets, the airframe of this light bomber was based on curved lines with flying surfaces (including a T-tail) of modest sweep. Power was provided by two engines located in the wing roots, and the design envisaged an 11,023-lb (5000-kg) bombload carried internally plus a defensive armament of four 15-mm cannon in a TV-controlled tail barbette. Validation of the design was entrusted to a pair of reduced-scale machines, the engineless NC.271-01 and the rocket-powered NC.271-02. The NC.271-01 flew in 1949 (air-launched from a piggyback position above a Languedoc transport aeroplane), but before the NC.271-02 could be flown later in the same year the parent company folded and the whole NC.270 programne was terminated.