Engines: 4 x jet

Wngspan: 2m

Max speed: 300 kph

Endurance: 10 min

Fuel capacity: 30 lt

The Rolls-Royce Turbomeca Adour is a two-shaft turbofan aircraft engine developed by Rolls-Royce Turbomeca Limited, a joint subsidiary of Rolls-Royce (UK) and Turbomeca (France). The Adour is a turbofan engine developed primarily to power the Anglo-French SEPECAT Jaguar fighter-bomber, achieving its first successful test run in 1968.

Ten prototype engines were built for testing by both Rolls-Royce and Turbomeca, and 25 were built as development engines for the Jaguar prototypes,

Named after the Adour, a river in south western France, it was produced in versions with or without reheat.

As of July 2009 more than 2,800 Adours have been produced, for over 20 different armed forces with total flying hours reaching 8 million in December 2009. The U.S. military designation for this engine is the F405-RR-401 (a derivative of the Adour Mk 871), which is used to power the fleet of Boeing / BAE Systems T-45 Goshawk trainer jets of the US Navy.

Variants:

Reheated (Afterburning)

Adour Mk 101 – First production variant for the Jaguar, 40 built.

Adour Mk 102 – Second production variant with the addition of part-throttle reheat.

Adour Mk 104

Adour Mk 106 – Replacement for the Jaguar’s Mk104 engine (developed from the Adour 871) with a reheat section. The RAF refitted its fleet with this engine as part of the GR3 upgrade. In May 2007, following the retirement of the last 16 Jaguars from No. 6 Squadron RAF, based at RAF Coningsby, the Adour 106 has been phased out of RAF service.

Adour Mk 801 – For Mitsubishi F-1 & T-2 (JASDF)

TF40-IHI-801A – Licence-built version of Mk 801 by Ishikawajima-Harima for Mitsubishi F-1 & T-2 (JASDF)

Adour Mk 804 – Licence-built by HAL for Indian Air Force phase 2 Jaguars

Adour Mk 811 – Licence-built by HAL for Indian Air Force phase 3 to 6 Jaguars

Adour Mk 821 – Engine upgrade of Mk804 and Mk811 engines, under development, for Indian Air Force Jaguar aircraft.

Dry (Non-afterburning)

Adour Mk 151

Adour Mk 151A – Used by the Red Arrows,

Adour Mk 851

Adour Mk 861

Adour Mk 871

F405-RR-401 – Similar configuration to Mk 871, for US Navy T-45 Goshawk.

Adour Mk 951 – Designed for the latest versions of the BAE Hawk and powering the BAE Taranis and Dassault nEUROn UCAV technology demonstrators. The Adour Mk 951 is a more fundamental redesign than the Adour Mk 106, with improved performance (rated at 6,500 lbf (29,000 N) thrust) and up to twice the service life of the 871. It features an all-new fan and combustor, revised HP and LP turbines, and introduces Full Authority Digital Engine Control (FADEC). The Mk 951 was certified in 2005.

F405-RR-402 – Upgrade of F405-RR-401, incorporating Mk 951 technology, certified 2008. Expected entry into service 2012.

Applications:

BAE Hawk

McDonnell Douglas T-45 Goshawk

SEPECAT Jaguar

Licence-built

Ishikawajima-Harima TF40-IHI-801A

Mitsubishi F-1

Mitsubishi T-2

Specifications:

Adour Mk 106

Type: Turbofan

Length: 114 inches (2.90 m)

Diameter: 22.3 inches (0.57 m)

Dry weight: 1,784 lb (809 kg)

Compressor: 2-stage LP, 5-stage HP

Turbine: 1-stage LP, 1-stage HP

Maximum thrust: 6,000 lb (27.0 KN) dry / 8,430 lb (37.5 KN) with reheat

Overall pressure ratio: 10.4

Fuel consumption: dry 0.81(lb/hr/lb)

Thrust-to-weight ratio: 4.725:1

The Rolls-Royce RR500 is a small gas turbine engine developed by Rolls-Royce Corporation . The RR500TP turboprop variant was intended for use in small aircraft. The RR500TS is the turboshaft variant designed for light helicopters.

The RR500 is a larger derivative of the Rolls-Royce RR300 turboshaft, with the engine core scaled-up for increased power.

The basic weight of the engine with accessories is 250 lb (113 kg). The model produces around 500 shp (373 kW) for takeoff and can produce 380 shp (280 kW) in continuous use. Like its predecessor the Rolls-Royce Model 250 and all turbine engines (including the competing Pratt & Whitney Canada PT6), it will use jet fuel rather than avgas. It is also claimed to require less frequent maintenance than piston engines of similar power, albeit with the higher maintenance costs associated with turbine engines.

A RR500TS turboshaft variant was under development.

Variants:

RR500TP

RR500TS

Specifications:

RR500 proposed

Type: Twin-spool turboprop

Length: 43.1 in

Diameter: 23.4 in

Dry weight: 250 lbs (113 kg)

Compressor: Single-stage centrifugal

Maximum power output: 450 shp

Overall pressure ratio: 7.5:1

Fuel consumption: 27.4 gph (cruise)

Power-to-weight ratio: 2.0:1 hp/lbs at shaft (estimated)

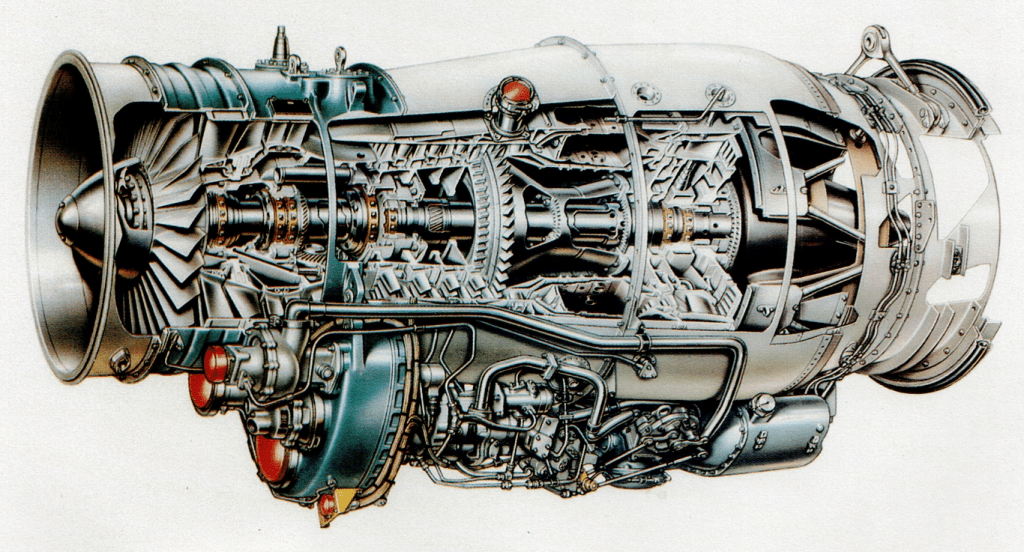

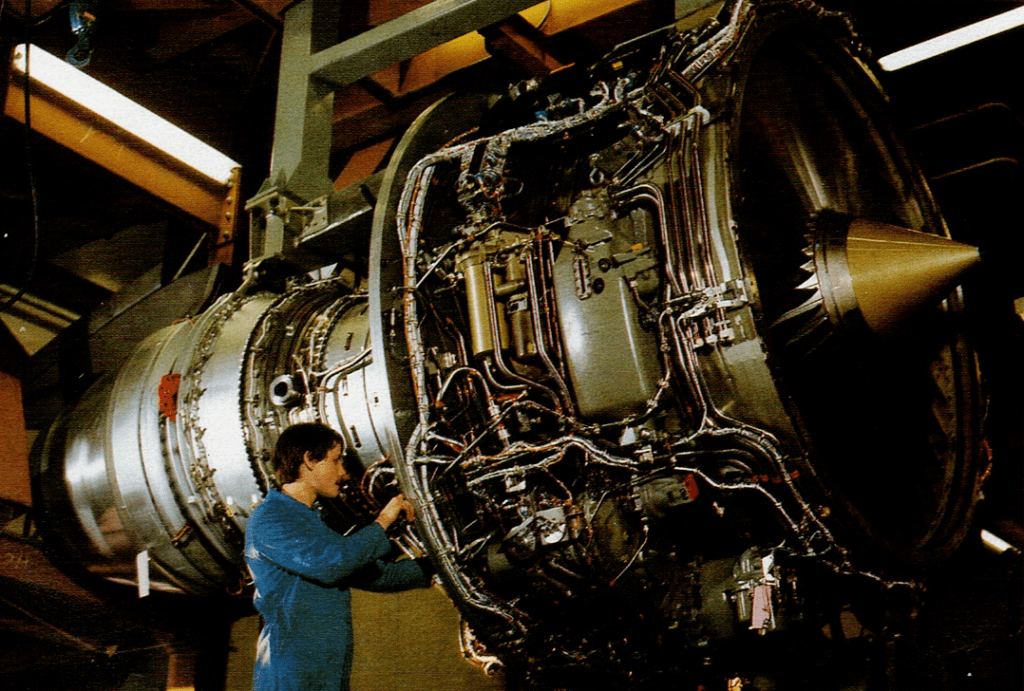

First run in 1969, the Rolls-Royce RB211 is a family of high-bypass turbofan engines made by Rolls-Royce plc and capable of generating 37,400 to 60,600 pounds-force (166 to 270 kilonewtons) thrust.

Originally developed for the Lockheed L-1011 TriStar, it entered service in 1972 and was the only engine to power this type of aircraft. It was not, as often believed, the costs of development which forced Rolls-Royce Limited into bankruptcy, but a financial management error which saw revenue from the RB211 sales to Lockheed retained in the US in US$ bank accounts, whereas all the company’s costs were incurred in pounds sterling. An adverse shift in exchange rates then triggered the bankruptcy. British Prime Minister Edward Heath considered the company so important to UK interests he opted for nationalisation and it became Rolls-Royce (1971) Limited. Its RB211 engine was the first three-spool engine, and it was to turn Rolls-Royce from a significant player in the aero-engine industry into a global leader. Already in the early 1970s the engine was reckoned by the company to be capable of at least 50 years of continuous development.

In 1966 American Airlines announced a requirement for a new short-medium range airliner with a focus on low-cost per-seat operations. While they were looking for a twin-engined plane, the aircraft manufacturers needed more than one customer to justify developing a new airliner. Eastern Airlines were also interested, but needed greater range and needed to operate long routes over water; at the time this demanded three engines in order to provide redundancy. Other airlines were also in favour of three engines. Lockheed and Douglas responded with designs, the L-1011 TriStar and DC-10 respectively. Both had three engines, transcontinental range and seated around 300 passengers in a widebody layout with two aisles.

Both planes also required new engines. Engines were undergoing a period of rapid advance due to the introduction of the high bypass concept, which provided for greater thrust, improved fuel economy and less noise than the earlier low-bypass designs. Rolls-Royce had been working on an engine of the required 45,000 lbf (200 kN) thrust class for an abortive attempt to introduce an updated Hawker Siddeley Trident as the RB178. This work was later developed for the 47,500 lbf (211 kN) thrust RB207 to be used on the Airbus A300, before it was cancelled in favour of the RB211 programme.

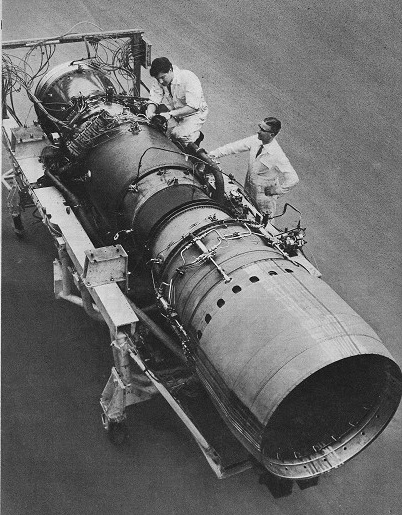

Meanwhile Rolls-Royce was also working on a series of triple-spool[3] designs as replacements for the Conway, which promised to deliver higher efficiencies. In this configuration, three groups of turbines spin three separate concentric shafts to power three sections of the compressor area running at different speeds. In addition to allowing each stage of the compressor to run at its optimal speed, the triple-spool design is also more compact and rigid, although more complex to build and maintain. Several designs were being worked on at the time, including a 10,000 lbf (44 kN) thrust design known as the RB203 intended to replace the Rolls-Royce Spey. Work started on the Conway replacement engine in July 1961 and a twin-spool demonstrator engine to prove the HP compressor, combustor, and turbine system designs, had been run by 1966. Rolls-Royce chose the triple-spool system in 1965 as the simplest, lowest cost solution to the problem of obtaining lower fuel consumption and reduced noise levels at a constant power setting. Work on the RB211 as essentially a scaled-down RB207 began in 1966-7 with the first certificated engines being scheduled to be available by December 1970 at 33,260lb take-off thrust and at a price of $511,000 each.

On 23 June 1967, Rolls-Royce offered Lockheed the RB211-06 for the L-1011. The new engine was to be rated at 33,260 lbf (147,900 N) thrust and combined features of several engines then under development: the large high-power, high-bypass design from the RB207 and the triple-spool design of the RB203. To this they added one totally new piece of technology, a fan stage built of a new carbon fibre material called Hyfil developed at RAE Farnborough. The weight savings were considerable over a similar fan made of steel, and would have given the RB211 an advantage over its competitors in terms of power-to-weight ratio. Despite knowing that the timescale would be challenging for an engine incorporating these new features, Rolls-Royce committed to putting the RB211 into service in 1971.

Lockheed felt the new engine would offer a distinct advantage over the otherwise similar DC-10 product. However, Douglas had also requested proposals from Rolls for an engine to power its DC-10, and in October 1967 Rolls responded with a 35,400 lbf (157,000 N) thrust version of the RB211 designated the RB211-10. There followed a period of intense negotiations between airframe manufacturers Lockheed and Douglas, potential engine suppliers Rolls-Royce and General Electric and Pratt & Whitney, as well as the major U.S. airlines. During this time prices were negotiated downwards, while the required thrust ratings were raised ever higher. By early 1968, Rolls was offering a 40,600 lbf (181,000 N) thrust engine designated RB211-18. Finally, on 29 March 1968 Lockheed announced that it had received orders for 94 TriStars, and placed an order with Rolls-Royce for 150 sets of engines designated RB211-22.

The RB211’s complexity required a lengthy development and testing period. By Autumn 1969 Rolls-Royce was struggling to meet the performance guarantees to which it had committed: the engine had insufficient thrust, was over-weight and its fuel consumption was too high. The situation deteriorated further when in May 1970 the new Hyfil (a Carbon (fiber) composite) fan stage, after passing every other test, shattered into pieces when a chicken was fired into it at high speed. Rolls had been developing a titanium blade as an insurance against difficulties with Hyfil, but this meant extra cost and more weight. It also brought its own technical problems when it was discovered that only one side of the titanium billet was of the right metallurgical quality for blade fabrication.

In September 1970, Rolls-Royce reported to the government that development costs for the RB211 had risen to £170.3 million – nearly double the original estimate; furthermore the estimated production costs now exceeded the £230,375 selling price of each engine. The project was in crisis.

By January 1971 Rolls-Royce had become insolvent, and on 4 February 1971 was placed into receivership,[note 1] seriously jeopardising the L-1011 TriStar programme. Because of its strategic importance, the company was nationalised by the then-Conservative government of Edward Heath, allowing development of the RB211 to be completed.

As Lockheed was itself in a vulnerable position, the government required that the US government guarantee the bank loans that Lockheed needed to complete the L-1011 project. If Lockheed (which was itself weakened by the difficulties) had failed, the market for the RB211 would have evaporated. Despite some opposition, the US government provided these guarantees. In May 1971, a new company called “Rolls-Royce (1971) Ltd.” acquired the assets of Rolls-Royce from the Receiver, and shortly afterwards signed a new contract with Lockheed. This revised agreement cancelled penalties for late delivery, and increased the price of each engine by £110,000.

Kenneth Keith, the new chairman who had been appointed to rescue the company, persuaded Stanley Hooker to come out of retirement and return to Rolls. As technical director he led a team of other retirees to fix the remaining problems on the RB211-22. The engine was finally certified on 14 April 1972, about a year later than originally planned, and the first TriStar entered service with Eastern Air Lines on 26 April 1972. Hooker was knighted for his role in 1974.

The RB211’s initial reliability in service was not as good as had been expected because of the focus of the development programme on meeting the engine’s performance guarantees. Early deliveries were of the RB211-22C model, derated slightly from the later -22B. However, a programme of modifications during the first few years in service improved matters considerably, and the series has since matured into a highly reliable engine.

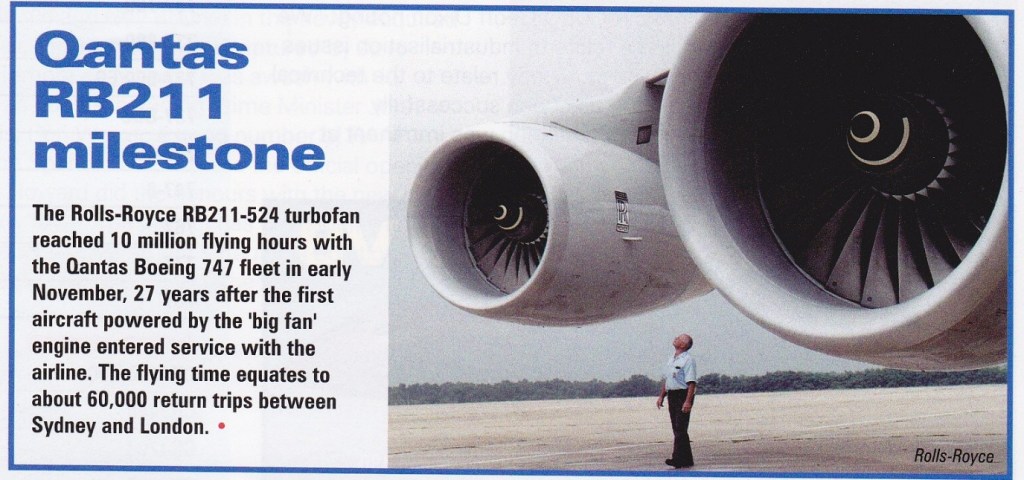

Although originally designed for the L-1011-1, Rolls-Royce knew that the RB211 could be developed to provide greater thrust. By redesigning the fan and the IP compressor, Hooker’s team managed to increase the engine’s thrust to 50,000 lbf (220 kN). The new version was designated RB211-524, and would be able to power new variants of the L-1011, as well as the Boeing 747.

Rolls-Royce had tried without success to sell the RB211 to Boeing in the 1960s, but the new -524 offered significant performance and efficiency improvements over the Pratt & Whitney JT9D which Boeing had originally selected to power the 747. In October 1973 Boeing agreed to offer the RB211-524 on the 747-200, and British Airways became the first airline to order this combination which entered service in 1977. Rolls continued to develop the -524, increasing its thrust through 51,500 lbf (229 kN) with the -524C, then 53,000 lbf (240 kN) in the -524D which was certificated in 1981.

Notable airline customers included Qantas, Cathay Pacific, Cargolux and South African Airways. When Boeing launched the larger 747-400 still more thrust was required, and Rolls responded with the -524G rated at 58,000 lbf (260 kN) thrust and then the -524H with 60,600; these were the first versions to feature FADEC. The -524H was also offered as a third engine choice on the Boeing 767, and the first of these entered service with British Airways in February 1990.

These would have been the final developments of the -524, but when Rolls developed the successor Trent engine, it found it could fit the Trent 700’s improved HP system to the -524G and -524H. These variants were lighter and offered improved fuel efficiency and reduced emissions; they were designated -524G-T and -524H-T respectively. It was also possible to upgrade existing -524G/H engines to the improved -T configuration, and a number of airlines did this.

The -524 became increasingly reliable as it was developed, and the -524H achieved 180-minute ETOPS approval on the 767 in 1993.

In the mid 1970s, Boeing was considering designs for a new twin-engined aircraft to replace its highly successful 727. As the size of the proposed plane grew from 150 passengers towards 200, Rolls-Royce realised that the RB211 could be adapted by reducing the diameter of the fan and removing the first IP compressor stage to produce an engine with the necessary 37,400 lbf (166,000 N) thrust. The new version was designated RB211-535. On 31 August 1978 Eastern Airlines and British Airways announced orders for the new 757, powered by the -535. Designated RB211-535C, the engine entered service in January 1983; this was the first time that Rolls-Royce had provided a launch engine on a Boeing aircraft.

However, in 1979 Pratt & Whitney launched its PW2000 engine, claiming 8% better fuel efficiency than the -535C for the PW2037 version. Boeing put Rolls-Royce under pressure to supply a more competitive engine for the 757, and using the more advanced -524 core as a basis, the company produced the 40,100 lbf (178,000 N) thrust RB211-535E4 which entered service in October 1984. While still not quite as efficient as the PW2037, it was more reliable and quieter. It was also the first to use the wide chord fan which increases efficiency, reduces noise and gives added protection against foreign object damage. As a result, a relatively small number of -535C’s were installed on production aircraft, the majority using the -535E.

As well as a featuring a destaged IP compressor, the -535E4 was the first engine to incorporate a hollow wide chord, unsnubbered fan to improve efficiency. It also featured the use of more advanced materials, including titanium in the HP compressor and carbon composites in the nacelle. Later engines incorporate some features (e.g. FADEC) from improved models of the -524.

Probably the most important single -535E order came in May 1988 when American Airlines ordered 50 757s powered by the -535E4 citing the engine’s low noise as an important factor: this was the first time since the TriStar that Rolls-Royce had received a significant order from a US airline, and it led to the -535E4’s subsequent market domination on the 757. Humorously (as reported in Air International) at the time of the announcement made by American, selection of the -535E4 was made public prior to the selection of the 757, though this was welcome news to both Rolls-Royce and Boeing.

After being certified for the 757, the E4 was offered on the Russian Tupolev Tu-204-120 airliner, entering service in 1992. This was the first time a Russian airliner had been supplied with western engines. The -535E4 was also proposed by Boeing for re-engining the B-52H Stratofortress, replacing the aircraft’s eight TF33s with four of the turbofans. Further upgrading of the -535E4 took place in the late 1990s to improve the engine’s emissions performance, borrowing technology developed for the Trent 700.

The -535E4 achieved 180-minute ETOPS approval on the 757 in 1990.

The RB211 was officially superseded in the 1990s by the Rolls-Royce Trent family of engines, the conceptual offspring of the RB211.

The family is divided into three distinct series:

RB211-22 series

Triple-spool high-bypass-ratio 5.0

Single-stage wide-chord fan

Seven-stage IP compressor

Six-stage HP compressor

Single annular combustor with 18 fuel burners

Single-stage HP turbine

Single-stage IP turbine

Three-stage LP turbine

RB211-524 series

Triple-spool high-bypass-ratio 4.3 – 4.1

Single-stage wide-chord fan

Seven-stage IP compressor

Six-stage HP compressor

Single annular combustor with 18 fuel burners (24 on the G/H-T)

Single-stage HP turbine

Single-stage IP turbine

Three-stage LP turbine

RB211-535 series

Triple-spool high-bypass-ratio 4.3 – 4.4

Single-stage wide-chord fan

Six-stage IP compressor

Six-stage HP compressor

Single annular combustor with 18 fuel burners (24 on later versions of E4)

Single-stage HP turbine

Single-stage IP turbine

Three-stage LP turbine

Specifications:

RB211-22B

Static thrust: 42,000 lbf (190 kN)

Basic engine weight: 9,195 lb (4,171 kg)

Length: 119.4 in

Fan diameter: 84.8 in (2.15 m)

Entry into service: 1972

Applications: Lockheed L-1011-1, Lockheed L-1011-100

RB211-524B2

Static thrust: 50,000 lbf (220 kN)

Basic engine weight: 9,814 lb (4,452 kg)

Length: 119.4 in

Fan diameter: 84.8 in (2.15 m)

Entry into service: 1977

Applications: Boeing 747-100, Boeing 747-200, Boeing 747SP

RB211-524B4

Static thrust: 53,000 lbf (240 kN)

Basic engine weight: 9,814 lb (4,452 kg)

Length: 122.3 in

Fan diameter: 85.8 in (2.18 m)

Entry into service: 1981

Applications: Lockheed L-1011-250, Lockheed L-1011-500

RB211-524C2

Static thrust: 51,500 lbf (229 kN)

Basic engine weight: 9,859 lb (4,472 kg)

Length: 119.4 in

Fan diameter: 84.8 in (2.15 m)

Entry into service: 1980

Applications: Boeing 747-200, Boeing 747SP

RB211-524D4

Static thrust: 53,000 lbf (240 kN)

Basic engine weight: 9,874 lb (4,479 kg)

Length: 122.3 in

Fan diameter: 85.8 in (2.18 m)

Entry into service: 1981

Applications: Boeing 747-200, Boeing 747-300, Boeing 747SP

RB211-524D4-B

Static thrust: 53,000 lbf (240 kN)

Basic engine weight: 9,874 lb (4,479 kg)

Length: 122.3 in

Fan diameter: 85.8 in (2.18 m)

Entry into service: 1981

Applications: Boeing 747-200, Boeing 747-300

RB211-524G

Static thrust: 58,000 lbf (260 kN)

Basic engine weight: 9,670 lb (4,390 kg)

Length: 125 in

Fan diameter: 86.3 in (2.19 m)

Entry into service: 1989

Applications: Boeing 747-400

RB211-524H

Static thrust: 60,600 lbf (270 kN)

Basic engine weight: 9,670 lb (4,390 kg)

Length: 125 in

Fan diameter: 86.3 in (2.19 m)

Entry into service: 1990

Applications: Boeing 747-400, Boeing 767-300

RB211-524G-T

Static thrust: 58,000 lbf (260 kN)

Basic engine weight: 9,470 lb (4,300 kg)

Length: 125 in

Fan diameter: 86.3 in (2.19 m)

Entry into service: 1998

Applications: Boeing 747-400, Boeing 747-400F

RB211-524H-T

Static thrust: 60,600 lbf (270 kN)

Basic engine weight: 9,470 lb (4,300 kg)

Length: 125 in

Fan diameter: 86.3 in (2.19 m)

Entry into service: 1998

Applications: Boeing 747-400, Boeing 747-400F, Boeing 767-300

RB211-535C

Static thrust: 37,400 lbf (166 kN)

Basic engine weight: 7,294 lb (3,309 kg)

Length: 118.5 in

Fan diameter: 73.2 in (1.86 m)

Entry into service: 1983

Applications: Boeing 757-200

RB211-535E4

Static thrust: 40,100 lbf (178 kN)

Basic engine weight: 7,264 lb (3,295 kg)

Length: 117.9 in

Fan diameter: 74.1 in (1.88 m)

Entry into service: 1984

Applications: Boeing 757-200, Boeing 757-300, Tupolev Tu-204

RB211-535E4B

Static thrust: 43,100 lbf (192 kN)

Basic engine weight: 7,264 lb (3,295 kg)

Length: 117.9 in

Fan diameter: 74.1 in (1.88 m)

Entry into service: 1989

Applications: Boeing 757-200, Boeing 757-300, Tupolev Tu-204

The Rolls-Royce BR700 family of engines was developed by BMW and Rolls-Royce plc through the joint venture company BMW Rolls-Royce AeroEngines GmbH to power regional jets and corporate jets. Rolls-Royce took full control of the company in 2000, which is known as Rolls-Royce Deutschland. The company was established in 1990 and the first engine run (BR710) took place in September 1994.

The engine is manufactured in Dahlewitz, Germany.

The BR710 is a twin shaft turbofan, entered service on the Gulfstream V in 1997 and the Bombardier Global Express in 1998. This version has also been selected to power the Gulfstream G550. Another rerated version, with a revised exhaust system, was selected for the now cancelled Royal Air Force Nimrod MRA4s.

The BR710 comprises a 48in diameter single stage fan, driven by a two stage LP turbine, supercharging a ten stage HP compressor (scaled from the V2500 unit) and driven by a two stage, air-cooled, HP turbine.

The BR715 is another twin shaft turbofan, this engine was first run in April 1997 and entered service in mid-1999. This version powers the Boeing 717.

A new LP spool, comprising a 58in diameter single stage fan, with two stage LP compressor driven by a three stage LP turbine, is incorporated into the BR715. The HP spool is similar to that of the BR710.

The IP compressor booster stages supercharge the core, increasing core power and thereby net thrust. However, a larger fan is required, to keep the specific thrust low enough to satisfy jet noise considerations.

The BR725 is a variant of the BR710 with a three stage-axial flow low pressure turbine to power the Gulfstream G650. The engine has a maximum thrust of 17,000 pounds-force (75.6 kN). The BR725 has a bypass ratio of 4.2:1, and is 4 dB quieter than the predecessor BR710. Its 50-inch (127 cm) fan assembly consists of 24 swept titanium blades.

The BR725 prototype underwent component bench and its first full engine run in spring 2008 and European certification was achieved in June 2009. The first Gulfstream G650, with BR725 engines, was delivered in December 2011.

Variants:

BR700-710A1-10

Variant with a 65.6kN take-off rating and a maximum diameter of 1820mm.

BR700-710A2-20

Variant with a 65.6kN take-off rating and a maximum diameter of 1820mm.

BR700-710B3-40

Variant with a 69kN take-off rating for the BAE Systems Nimrod MRA4.

BR700-710C4-11

Variant with a 68.4kN take-off rating and a maximum diameter of 1785mm.

BR700-715A1-30

Variant with an 83.23kN take-off rating for Boeing 717-200 basic gross weight variants.

BR700-715B1-30

Variant with an 89.68kN take-off rating.

BR700-715C1-30

Variant with a 95.33kN take-off rating for Boeing 717-200 high gross weight variants.

BR700-725A1-12

Variant with a 71.6kN take-off rating.

Applications:

Bombardier Global Express

Boeing 717

Gulfstream V

Gulfstream G650

BAE Systems Nimrod MRA4

Rekkof/ Fokker XF70/XF100

Tupolev Tu-334

Specifications:

BR710-48

Thrust: 14,750-15,500 lb

Dry Weight: 4640 lb

Overall Length: 134.0 in

Fan Diameter: 48.0 in

BR715-58

Thrust: 18,500-22,000 lb

Dry Weight: 6155 lb

Overall Length: 147.0 in

Fan Diameter: 58.0 in

BR725-50

Thrust: 15,000-17,000 lb

Dry Weight: 4912 lb appx

Overall Length: 202.0 in nacelle

Fan Diameter: 50.0 in

In 1954 Rolls-Royce introduced the first commercial bypass engine, the Rolls-Royce Conway, with a 21,000 lbf (94 kN) thrust aimed at what was then the “large end” of the market. This was far too large for smaller aircraft such as the Sud Caravelle, BAC One-Eleven or Hawker Siddeley Trident which were then under design. Rolls then started work on a smaller engine otherwise identical in design, the RB.163, using the same two-spool turbine system and a fairly small fan delivering bypass ratios of about 0.64:1. In keeping with Rolls-Royce naming practices, the engine is named after the River Spey.

The first versions entered service in 1964, powering both the 1-11 and Trident. Several versions with higher power ratings were delivered through the 1960s, but development was ended nearing the 1970s due to the introduction of engines with much higher bypass ratios, and thus better fuel economy. Spey-powered airliners continued in widespread service until the 1980s, when noise limitations in European airports forced them from service.

In the late 1950s the Soviet Union started the development of a new series of large cruisers that would put the Royal Navy at serious risk. After studying the problem, the RN decided to respond in a “non-linear” fashion, and instead of producing a series of new cruisers themselves, they would introduce a new strike aircraft with the performance needed to guarantee successful attacks on the Soviet fleet. The winning design was the Blackburn Buccaneer, which had an emphasis on low altitude performance (i.e. to evade enemy radar) as opposed to outright speed.

Flying at low altitude, in denser air, requires much more fuel; the air-fuel mixture in a jet engine needs to be kept very close to a constant value to burn properly, and more air requires proportionally more fuel. This presented a serious problem for aircraft such as the Buccaneer, which would have had very short range unless the engines were optimised for low-level flight. The early pre-production versions, powered by the de Havilland Gyron Junior, also proved to be dangerously underpowered.

Rolls-Royce attacked this problem by offering a militarized version of the Spey, which emerged as the RB.168. The resulting Spey-powered Buccaneer S.2 served into the 1990s. The Spey proved so successful in this role that it was produced under license, and developed, in the United States as the TF41 and F113, and was used in a number of British and US designs.

The British versions of the McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II F-4K (designated Phantom FG.Mk.1) replaced the 16,000 lb thrust J79 turbojets with a pair of 12,250 lb thrust dry and 20,515 lb thrust with afterburning RB.168-15R Spey 201 turbofans. These provided extra thrust for operation from smaller British aircraft carriers, and provided additional bleed air for the boundary layer control system for slower landing speeds. The air intake area was increased by twenty percent, while the aft fuselage under the engines had to be redesigned. Compared to the original turbojets, the afterburning turbofans produced a ten and fifteen percent improvement in combat radius and ferry range, respectively, and improved take-off, initial climb, and acceleration, but a lower top speed.

A fully updated version of the military RB.168 was also built to power the AMX International AMX attack aircraft. A licensed version built by the XAEC is known as the WS-9 Qin Ling.

With the need for a 10,000 to 15,000 lbf (44 to 67 kN) thrust class engine starting up again with the removal of the Spey from service, Rolls then used the Spey turbomachinery with a much larger fan to produce the Rolls-Royce Tay.

A total of 2,768 were built.

Variants:

RB.163-1

RB.163-2

RB.163-2W

RB.163 Mk.505-5

RB.163 Mk.505-14

RB.163 Mk.506-5

RB.163 Mk.506-14

RB.163 Mk.511-8

Gulfstream II and Gulfstream III (USAF designation F113-RR-100 for the Gulfstream C-20)

RB.163 Mk.512-14DW

BAC One-Eleven

AR 963

(RB.163) Boeing 727 (proposed); it was to have been built under licence by Allison

F113-RR-100

US military designation for the Mk.511-8 engines fitted to the Gulfstream C-20.

RB.168-62

RB.168 Mk.101

(Military Spey) Blackburn Buccaneer

RB.168 Mk.202

(Military Spey) McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II modified F4J for British service (“Phantom FG1”). (surplus engines were purchased and used by Richard Noble for the Thrust SSC land speed record car of 1997.)

RB.168 Mk.250

(Military Spey) Hawker Siddeley Nimrod MR1/MR2

RB.168 Mk.251

(Military Spey) Hawker Siddeley Nimrod R1 and AEW

RB.168 Mk.807

AMX International AMX, built under licence by FiatAvio

WS-9 Qin Ling

(Mk 202) powering the Xian JH-7 (Xian FBC-1 Flying Leopard)

AR 168R

Joint development with Allison Engine Company for the TFX competition (won by the Pratt & Whitney TF30

Allison TF41

(RB.168-62 and Model 912) LTV A-7 Corsair II (USAF -D and US Navy -E models), licence built by the Allison Engine Company

RB.183 Mk 555-15 Spey Junior

Fokker F28

Marinised versions:

SM1A

Marinised Spey delivering 18,770 shp

SM1C

Marinised Spey delivering 26,150 shp

Specifications:

Spey Mk 202

Type: Low bypass turbofan

Length: 204.9 in (5204.4 mm)

Diameter: 43.0 in (1092.2 mm)

Dry weight: 4,093 lb (1856 kg)

Compressor: axial flow, 5-stage LP, 12-stage HP

Combustors: 10 can-annular combustion chambers

Turbine: 2-stage LP, 2-stage HP

Maximum thrust: Dry thrust: 12,140 lbf (54 kN); with reheat: 20,500 lbf (91.2 kN)

Thrust-to-weight ratio: 5:1

First run in December 1967, the Rolls-Royce RB.203 Trent was a British medium-bypass turbofan engine of around 10,000lb thrust, bearing no relation to the earlier Rolls-Royce RB.50 Trent turboprop or the later high bypass Rolls-Royce Trent turbofan.

The RB.203 was a private venture engine based around the core of the Rolls-Royce Turbomeca Adour turbofan used in the SEPECAT Jaguar and the later Hawker Siddeley Hawk.

The RB.203, the first three-spool engine, was intended as a civilian replacement for the earlier Rolls-Royce Spey.

Type: Three-spool medium bypass turbofan

Length: 82.2 in (208.8 cm)

Diameter: 38.7 in (98.3 cm)

Dry weight: 1,751 lb (794 kg)

Compressor: Single-stage fan, four-stage intermediate pressure, five-stage high pressure

Combustors: Annular chambers

Turbine: Single-stage high pressure, single-stage intermediate, two-stage low pressure

Maximum thrust: 16000 lb (71.4 kN)

Overall pressure ratio: 16:1

Bypass ratio: 3:1

Thrust-to-weight ratio: 5.55:1

The Rolls-Royce RB.162 was a simply constructed and lightweight British turbojet engine produced by Rolls-Royce Limited. Developed in the early 1960s, the RB.162 was designed to meet an anticipated need for a lift engine to power VTOL aircraft with the emphasis on simplicity, durability and lightweight construction. Development costs were shared by Britain, France and Germany after signing a joint memorandum of agreement. The engine featured fibre glass compressor casings and plastic compressor blades to save weight which also had the effect of reducing production costs. The engine has no oil system, a metered dose of oil instead being injected into the two main bearings by the compressed air used to turn the compressor at startup. Although the RB.162 was a successful design the expected large VTOL aircraft market did not materialise and the engine was only produced in limited numbers.

In 1966 British European Airways (BEA) had a requirement for an extended range aircraft to serve Mediterranean destinations. After a plan to operate a mixed fleet of Boeing 727 and 737 aircraft was not approved by the British Government Hawker Siddeley offered BEA a stretched and improved performance version of the Trident that they were already operating. This variant, the Trident 3B, used, in addition to its three Rolls-Royce Spey turbofan engines, a centrally mounted RB.162-86 which was used for takeoff and climb in the hot prevailing conditions of the Mediterranean area. The ‘boost’ engine was shut down for cruising flight. Some conversion was needed for the change from vertical to horizontal installation. With the RB.162 fitted the Trident 3B had a 15% increase in thrust over the earlier variants for an engine weight penalty of only 5%.

First run in January 1962, only 86 were built.

A design study for a turbofan version of the RB.162 was designated RB.175. Another projected derivative, the RB.181 was to be a scaled down version of the RB.162 producing approximately 2,000 lbs of thrust. Seven of these lift engines were to power the unbuilt Lockheed/Short Brothers CL-704 VTOL variant of the F-104 Starfighter.

Applications:

Dassault Mirage IIIV

Dornier Do 31

Hawker Siddeley Trident 3B

VFW VAK 191B

RB.162-86

Type: Single spool turbojet

Length: 51.6 in (1311 mm)

Diameter: 25.0 in (635 mm)

Dry weight: 280 lbs (127 kg)

Compressor: 6-stage axial flow

Combustors: Annular

Turbine: Single-stage axial flow

Maximum thrust: 5,250 lb (23 kN)

Thrust-to-weight ratio: 18.75:1

First run in 1953, the Rolls-Royce RB.106 was an advanced military turbojet engine by Rolls-Royce and was sponsored by the Ministry of Supply.

A two-shaft design with two axial flow compressors each driven by its own single stage turbine and reheat, it was of similar size to the Rolls-Royce Avon, allowing it to be used as a drop-in replacement, but it would have produced about twice the thrust at 21,750 lbf (96.7 kN). The two-shaft layout was relatively advanced for the era; the single-shaft de Havilland Gyron matched it in power terms, while the two-spool Bristol Olympus was much less powerful at the then-current state of development.

Apart from being expected to power British aircraft such as those competing for Operational Requirement F.155 it was selected to be the powerplant for the Avro Canada CF-105 Arrow. However funding was cut with the 1957 Defence White Paper which terminated most aircraft development then under way. The Arrow moved to an indigenous two-spool design similar to the RB.106, the Orenda Iroquois.

A scaled-up version of the RB106 intended for F.155 was the Rolls-Royce RB122. The RB.106 project was cancelled in March 1957, at a reported total cost of £ 100,000.

RB.106

Type: Two-shaft turbojet

Compressor: axial flow; LP followed by HP

Turbine: axial flow; HP single stage; LP single-stage

Maximum thrust: 21,750 lbf (96.7 kN)

The Rolls-Royce Turbomeca RTM322 is a turboshaft engine produced by Rolls-Royce Turbomeca Limited, a joint venture between Rolls-Royce plc and Turbomeca. The engine was designed to suit a wide range of military and commercial helicopter designs. The RTM322 can also be employed in maritime and industrial applications.

The first order for the RTM322 was received in 1992 to power 44 Royal Navy Merlin HM1s which subsequently entered service in 1998. According to Rolls-Royce 1,500 engines are made or ordered, and about 80% of AW101’s use the engine.

Applications:

AgustaWestland Apache

AgustaWestland AW101

NHIndustries NH90

Specifications:

Mk 250 or 02/8 variant

Type: Turboshaft

Length: 46.1 in (1.17 m)

Diameter: 25.5 in (0.65 m)

Dry weight: 503 lb (228 kg)

Compressor: 3HP + 1CFHP

Turbine: 2HP, 2PT

Maximum power output: 2,270 shp (1,693 kW)

Overall pressure ratio: 14.2