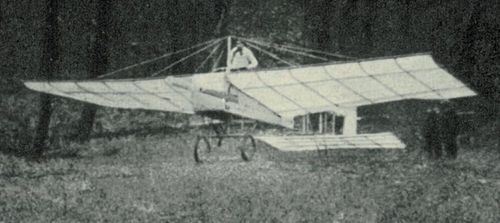

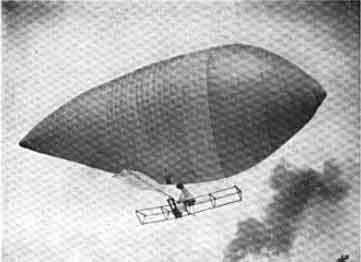

The ornithopter designed by Vladimir Tatlin from 1929 to 1932 and Tatlin built three versions of his machine. The word Letatlin is formed from the verb letat (fly), associated with the name of its creator, Tatlin. In the Stalin years, Tatlin, one of the major artists of the constructivist movement of the Soviet revolutionary years, designed his ornithopter inspired from birds.

Tatlin had carried out a trial flight that hadn’t worked out.

The ornithopter designed by Tatlin from 1929 to 1932 had disappeared. It had been more or less abandoned for twenty years in a warehouse belonging to the Molino Russian Federation Central Air force museum, next to Star City, the Youri-Gagarin cosmonaut training center fifty kilometers away from Moscow. It was the KSEVT, team, the space culture center in Slovenia, that by chance came across the machine in a precarious state during a protocol visit to the Monino museum in 2014. In February 2014, they were taken to the historical part of the Monino museum where one can see pioneers’ flying machines, since the Russians went into aeronautics very early. Miha Turšič, director of KSEVT until 2016, member of the collective Postgravityart, spotted the Letatlin in the corridors of the Monino museum in April 2014.

While the group was in discussion, Miha Turšič went ahead, getting a bit lost in the aisles of the museum, and suddenly I found myself face to face with a machine that looked like a plane but wasn’t one. He knew of the Letatlin and there it was right in front of him. We immediately asked if they knew what they had there, one of the most iconic works of 20th century art. They told us: “Yes, it’s an old Russian artist who built sort of flying machines rather like Leonardo de Vinci.” They had no idea of the importance of the piece. They considered it as best as an experimental flying machine that had never flown. Tatlin was mentioned, but with no context.

It was Letatlin n°3 that was found. It would have reached Monino in 1996 after being damaged on the way back from a presentation in an exhibition in Athens and was left there, abandoned in the context of complicated years following the collapse of the USSR.

The Molino Air force museum had just retrieved it a year earlier from the museum storeroom where it lay in bits in a corner, deteriorated, really damaged, and they had reassembled it to hang it in their museum.

It was obvious that a renovation was necessary for the Letatlin. The Monino museum and the Tretiakov gallery finally found an agreement for its renovation. Turšič went to Moscow at the end of December 2017 to meet the curator of the museum and saw it displayed in the 20th century art collection.

The Letatlin finally found the perfect place for its presentation to the public.