Origins of the B-52 stemmed from a specification issued through the Air Material Command (AMC) on November 23rd, 1945, calling for a long-range, intercontinental, high-altitude strategic bomber. Specifications included an operating radius of 4,340 nautical miles, a speed of 260 knots at altitude of 43,000 feet, and a bombload capacity of 10,000 pounds. In February of 1946, the Boeing Aircraft Company, Consolidated Aircraft Corporation and the Glenn L. Martin Company all responded. Boeing’s team devised the Model 462 as a straight-wing, multi-engine design powered by 6 x Wright T35 Typhoon turboprop engines rated at 5,500shp each. On June 5th, 1946, Model 462 was selected and designated XB-52. A full-scale mockup contract was then awarded.

By now, the USAAF was already looking beyond the qualities of the Model 462, fearing that the aircraft was already rendered obsolete in its conventional design approach and could never reach the intended goals of the original specification – especially in terms of its range. As such, the USAAF cancelled their contract with Boeing and the Model 462 was dead.

Boeing chief engineer Ed Wells took the Model 462 and evolved a pair of smaller concepts with four turboprops each appearing in their respective 464-16 and 464-17 forms. Essentially, the 464-16 was a short-range bomber made to carry a greater bombload while the 464-17 was a long-range bomber made to carry a smaller bombload. Neither idea stuck with the USAAF as a replacement for the B-36 though interest did center on the 464-17 design. Several more concepts were developed but interest on the part of the Air Force was waning. The Model 464-29 appeared, complete with swept-back wings at 20 degrees and fitting 4 x Pratt & Whitney turboprop engines. Again, this concept failed to answer the key points of the specification which, by now, was ever-changing to include increased performance specs along with long range.

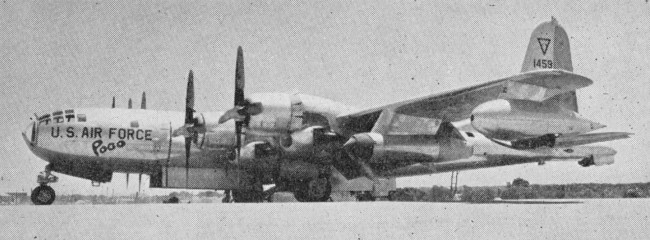

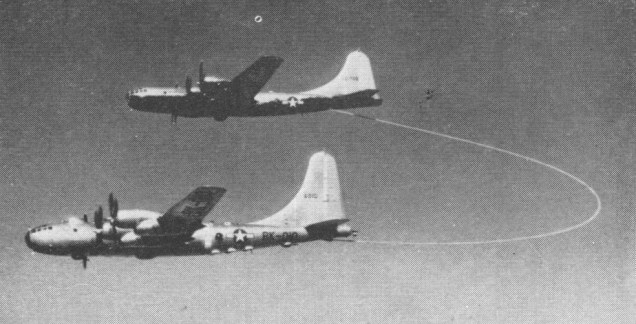

The Model 464-35 was another Boeing design team proposal fitting 4 x turboprop engines with contra-rotating propellers. Wing sweep was increased moreso than previous attempts, beginning to define the look of the Stratofortress. With in-flight refueling becoming more of a USAF operational norm, the design team now had some leeway in the overall size of their aircraft. Events in Europe in the latter part of the 1940’s pushed the XB-52 project forward, rewarding the Boeing Company with a hard-earned contract for a single mock-up and at least two flyable prototypes.

Upon a visit to Wright-Patterson AFB by the Boeing design team, it was learned that the USAF was now more interested in a jet-powered solution, seeing it as the only way to achieve the desired performance specs it required of the XB-52. In the course of a single weekend in a Dayton hotel room Ed Wells company set to work on new ideas for a Monday morning presentation. The resulting design combined elements of their Model 464-35 design with a four-engine, jet-powered medium bomber concept that had been brought along. The new aircraft became an eight-engine, Pratt & Whitney JT3 jet-powered heavy bomber with 35-degree swept wings. A small balsa wood model was constructed to further develop the idea and accompanied a detailed Model 464-49 design document of some 33 pages. The weekend effort paid off for Boeing as the USAF became greatly interested in the aircraft after Monday morning. The design was revised into the Model 464-67 and accepted for construction as two prototypes.

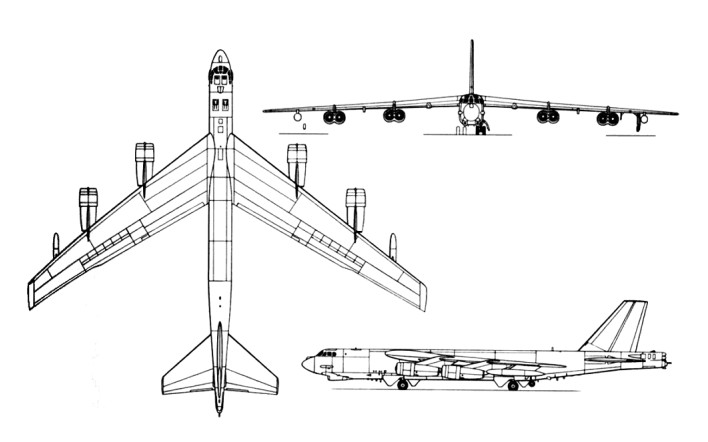

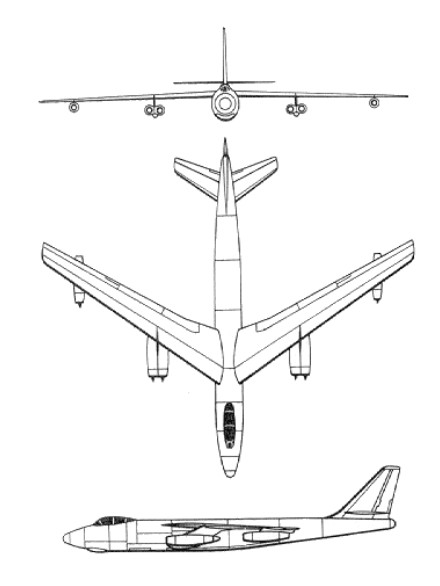

Eight engines were installed in twin pods hung under the 35 degree swept wing, and other unusual features included a vertical tail able to fold sideways to enter a hangar, wingtips that moved downwards 2.5 m (8 ft) as the wing tanks were filled, and four twin wheel landing trucks which can be swivelled for cross wind landings.

Boeing B-52 Stratofortress Article

An XB-52 production contract reached Boeing executives on February 14th, 1951. The contract called for 13 B-52A models. The XB-52 became the first prototype constructed and this was followed by the YB-52. The YB-52 received this evaluation due to the funding coming from the Air Force’s Logistics Command.

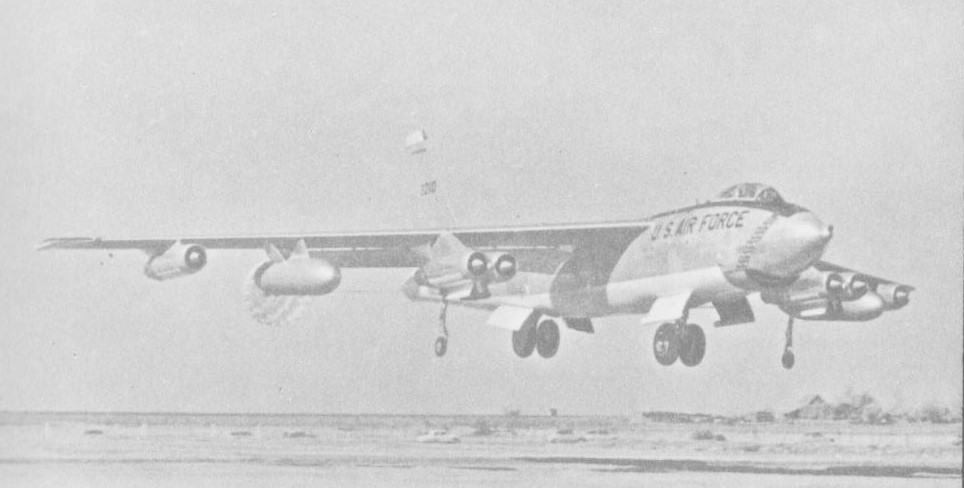

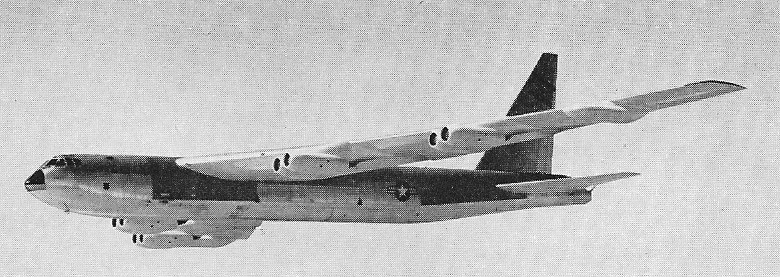

The YB-52 beat the XB-52 to flight testing on March 15th, 1952. The XB-52 was rolled out on November 29th, 1951, under the cover of night for secrecy’s sake but a pneumatic system failure caused enough damage to the wing trailing edge for the aircraft to be rolled back inside for lengthy repairs. As such, the YB-52 achieved its first flight on April 15th, 1952 and did not experience any major setbacks. The XB-52 finally got airborne on October 2nd, 1952. Both the XB-52 and the YB-52 featured tandem seating cockpits with upward firing ejection seats.

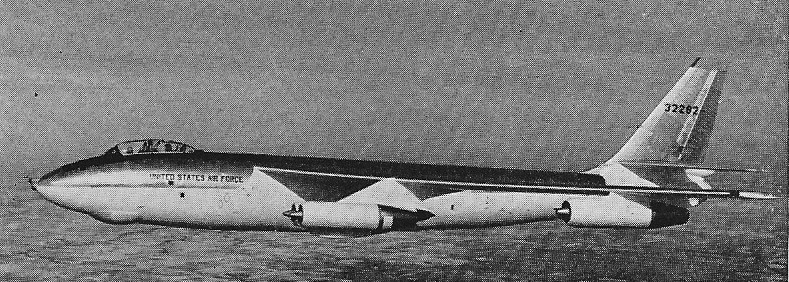

Only 3 B-52A’s built and the B-52B and RB-52B were in large-scale production for the U.S.A.F. in 1955. Both were equipped for flight refuelling. From the original order of 13 B-52A’s, ten were later earmarked for production as B-52B models. Compared to the twin prototypes, the three B-52A’s now featured the more conventional side-by-side cockpit seating arrangement in a revised forward fuselage along with the tail armament of 4 x 12.7mm Browning M3 machine guns. A distinguishing feature of A-models to B-models was the lack of a fully operational avionics suite. These aircraft were fitted with Pratt & Whitney J57-9W engines of 10,000lbf thrust each. The split-level cockpit featured seating for three on the upper deck and seating for two in the lower. The lower occupants were given downward-firing ejection seats. The tail gunner was removed from the rest of the crew and seated in his rear-facing turret station sans any type of ejection seat though the tail system could be ejected in the event of an accident. An unpressurized crawlspace was his only link to the front of the aircraft. In-flight refueling was accomplished via a boom connection above and behind the main flight deck. Other key additions included wing-mounted external fuel tanks to increase range and decrease “wing-flexing” across the span. Water injection was introduced to the J57 to assist in take-off. The two prototypes lacked the side-by-side cockpit seating arrangement and the in-flight refueling arrangement of the A-models and seating for the third upper deck crewmember (Electronic Warfare Officer – EWO). NB-52A – aka “The High and Mighty One” – was developed from the third B-52A flight test model. This aircraft (s/n 52-0003) was modified to act as the mothership in the launching of the experimental North American X-15 aircraft. NB-52B went on to become the longest flying B-52B airframe, ultimately seeing retirement in 2004.

By 1958 weight had increased, engines were rated at 5080 or 6124 kg (11,200 or 13500 lb) thrust with water injection, and new nav/bombing systems were fitted. While original B-52’s featured a 4 x 12.7mm collection of Browning M3 heavy machine guns in a rear turret, later production models switched over to a remote-controlled 1 x 20mm M61 cannon for self-defense. The tail armament was altogether removed in more modern Stratofortress forms with the onset of the missile age. However, it should noted that at least 2 Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21 “Fishbed” aircraft were destroyed in the Vietnam War by the tail gunner, with these aircraft kills credited to SSgt Samuel O. Turner and A1C Albert E. Moore – both kills achieved just days apart in December of 1972 from B-52D’s. In B-52D models the tail gunner externally accessed the rear portion of the aircraft via an entry hatch. In the revised G-models, the gunner was allocated to the main crew cabin (complete with an ejection seat fitted to the upper flight deck and facing aft with the ECM operator) and operated the tail gun via the AGS-15 Fire Control System and radar.

The B-52B was, in actuality, the first true Stratofortress production model and was already in development while the previous aircraft forms were being refined. They more essentially A-models with fully operational avionics suites and Pratt & Whitney J57-P-29W, J57-P-29WA or J57-P-19W series engines all rated at 10,500lbf thrust. The J57-P-19W’s were differentiated by having their compressor blades made of titanium instead of steel. First flight of these aircraft was achieved in December of 1954. B-models were the first model in the series to achieve operational service on June 29th in 1955, this occurring with the 93rd Bombardment Wing (themselves achieving operational status on March 12th, 1956) of the United States Air Force and coming in the form of an RB-52B reconnaissance model. The defensive tail armament remained the 4 x 12.7mm machine gun mounts for a time though some 16 B-52B and 18 RB-52B models were fitted with a more potent 2 x M24A-1 20mm cannon array and an different fire control system. When this proved ineffective, the final production B-52B’s reverted back to the 4 x 12.7mm formation.

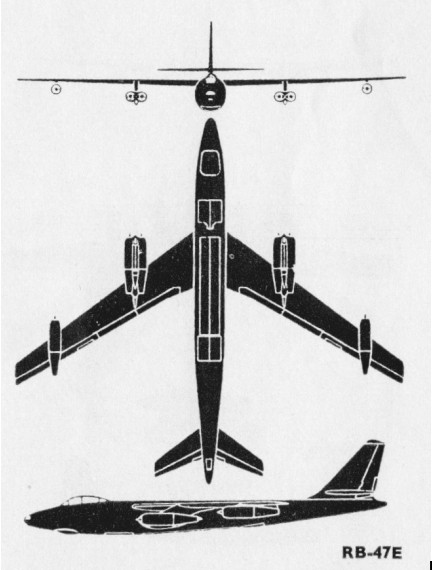

The B-52B was tested with atomic weapons on May 21st, 1956 – dropping a four megaton Mark 15 “Zombie” hydrogen bomb on the Bikini Atoll. Fifty B-52B models were produced in whole, with 27 of these being modified as special RB-52’s. RB-52’s represented reconnaissance-capable B-52B production models. These aircraft sported a crew of eight personnel and were fitted to accept specialized reconnaissance equipment in the form of a 300lb pod in their bomb bays, 40 ft fuel tanks in the wingtips, and up-rated J57 engines.

B-model combat load performance netted a top speed of 628 miles per hour with a service ceiling of 47,300 feet. The operational radius was equal to 3,576 miles.

The B-52C first flew on March 9, 1956 and officially came online in June of 1956 with 35 of the type seeing delivery. B-52C’s arrived with increased range thanks to improved fuel capacity made possible through larger external tanks. They were similar to B-models and operated with the same engine series. As this was the Cold War and the use of B-52’s in an all-out nuclear strike seemed all but imminent, the underside fuselage of B-52C models were painted over in an all-white scheme in an effort to reflect the thermal radiation inherent in a nuclear-induced explosion while their “tops” remained a natural metal finish. B-52B models were retrofitted with this white underside scheme. Bombloads for C-models topped 24,000lbs. B-52C’s were also reconnaissance capable though the RB-52C designation was never truly adopted for the type. Production of all C-models lasted through 1956.

On December 7, 1955, the first B-52 built at the Wichita Division of Boeing was rolled out. This was the second source of supply.

The B-52D became the first definitive high-quantity production Stratofortress ultimately produced in 170 examples and achieving first flight on May 14th, 1956. D-models entered service in December of 1956 as dedicated long-range bombers and, unlike previous Stratofortress offerings, these aircraft would not feature the ability to carry the reconnaissance pod so there were no RB-52D designations handed out. B-52D’s were used extensively in the Vietnam air war where their expansive bomb bays could be put to good use. Vietnam-based B-52D models were distinguished by their overall forest camouflage schemes and black-colored, anti-searchlight fuselage undersides. Production was split between Seattle and Wichita plants.

In January 1957 three B-52 flew around the world non-stop refuelling mid-air several times. They covered 24,325 miles at an average speed of 530 mph.

The B-52E first flew on October 17th, 1957, and followed D-models into operational service as improved Stratofortresses though they were quite similar to their predecessor. Improved air defenses across the Soviet Union forces a change to the high-level bombing strategy of early B-52’s. Therefore, the B-52E was developed into a low-level bomber. Additions included a revised bombing and navigation suite (AN/ASQ-38 – Raytheon AN/ASB-4 navigation and bombing radar) that would become standard on future Stratofortress production models. One hundred B-52E models were produced with the initial examples entering service in December of 1957. A single E-model was set aside for use as an in-flight test airframe and featured stabilizing canards.

The B-52F was similar to the preceding B-52E but sported Pratt & Whitney J57-43W series engines of 11,200lbf. Engine pods on each wing were revised to include their own water injection systems. F-models represented 89 production examples split between Seattle and Wichita to begin service in June of 1958. Among other refinements, these Stratofortresses featured new Pratt & Whitney J57-P-43W series turbojet engines. First flight was achieved on May 6th, 1958. First combat missions occurred via B-52F’s on June 18th, 1965.

While original B-52’s featured a 4 x 12.7mm collection of Browning M3 heavy machine guns in a rear turret, later production models switched over to a remote-controlled 1 x 20mm M61 cannon for self-defense. The tail armament was altogether removed in more modern Stratofortress forms with the onset of the missile age. However, it should noted that at least 2 Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21 “Fishbed” aircraft were destroyed in the Vietnam War by the tail gunner, with these aircraft kills credited to SSgt Samuel O. Turner and A1C Albert E. Moore – both kills achieved just days apart in December of 1972 from B-52D’s. In B-52D models the tail gunner externally accessed the rear portion of the aircraft via an entry hatch. In the revised G-models, the gunner was allocated to the main crew cabin (complete with an ejection seat fitted to the upper flight deck and facing aft with the ECM operator) and operated the tail gun via the AGS-15 Fire Control System and radar.

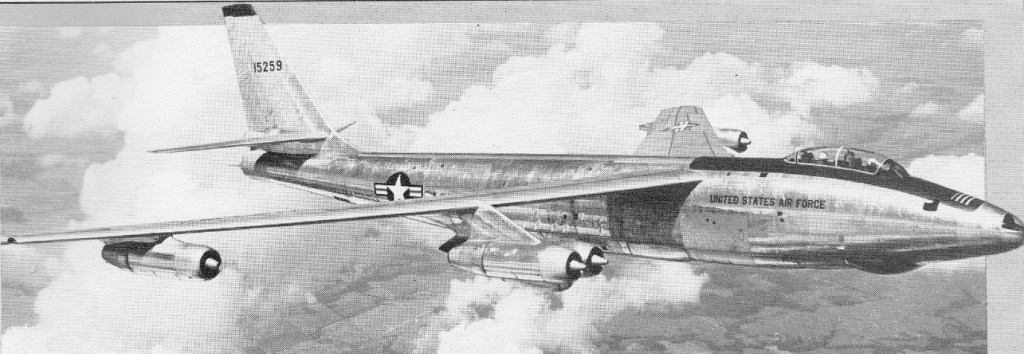

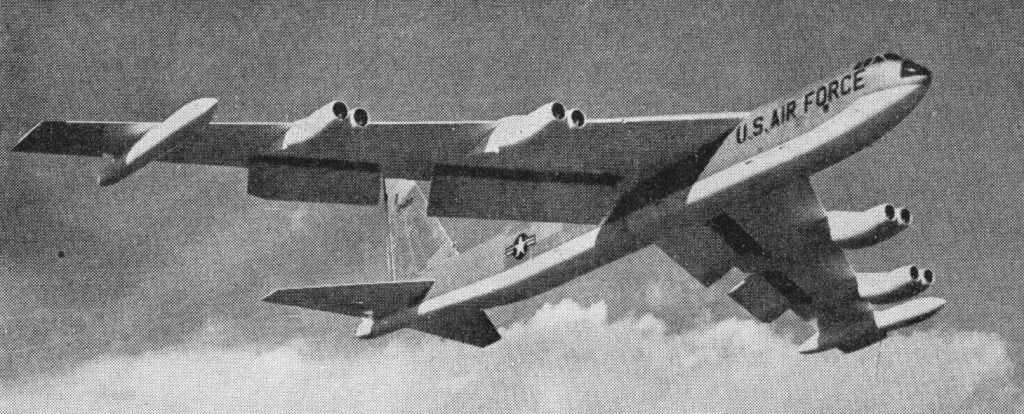

By 1959 production switched to the B 52G, with a great increase in fuel capacity, the entire crew in the nose, a new structure with a short fin, and pylons for two Hound Dog missiles. The B 52G demonstrated the range potential of the type when, in December 1960, an aircraft of the 5th Bombardment Wing flew 10,000 miles (16,093 km) in 19 hrs 45 mins. The B-52G was the most numerous version built (193).

The B-52G introduced sealed integral tank wings housing more fuel than previous models, as well as a shorter fin and a remotely controlled tail turret. Engines: Pratt & Whitney J57, 13,750 lb. Several tons were shaved off of the aircraft and crew accommodations were improved. The tail gunner was relocated to a new station within the main cabin area in the forward fuselage where the rest of the crew resided and given remote control of the turret. The vertical tail fin was shortened while the nose radome was lengthened and ailerons completely eliminated in favor of seven spoilers to provide for roll control. The G-model first flew on August 31st, 1958 and entering service on February 13th, 1959. G-models (55th production onwards) were outfitted with underwing pylons to accept the AGM-28/GAM-77 Hound Dog nuclear-tipped cruise missile – a feature also retrofitted on earlier production G-models. The Hound Dog missles could be run during takeoff to shorten the takeoff run. These Superfortresses were also later cleared to use 20 x AGM-69 SRAM nuclear missiles beginning in 1971. Four ADM-20 Quails (aircraft shaped decoys) were added in the bomb bay. Many B-52G’s would be sacrificed as part of the nuclear proliferation agreements between the United States and the Soviet Union beginning in 1992 while the surviving models were relegated to museum work. Production of G-models was handled by Wichita. The first 16 B-52Gs with cruise missiles became operational in December 1982.

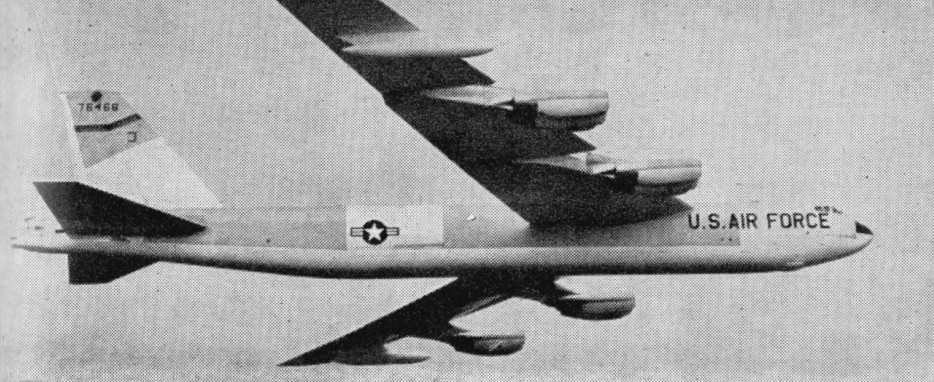

The B-52H model was first flown on March 6th, 1961 and introduced into service on May 9th, 1961. The B-52H model and designed to carry the GAM-87 Skybolt ballistic missile on four external pylons. Though essentially similar to the G-models it replaced, the B-52H sported improved performance and fuel efficient Pratt & Whitney TF33-P-3 turbofan engines of 17,000lbf and a reinforced understructure for improved low-level bombing. Major systems and subsystems were revised or improved as well and the 4 x 12.7mm tail gun armament was officially replaced by the remote-controlled 1 x 20mm General Electric M61 Vulcan six-barrel Gatling cannon system (6,000rpm) tied to an Emerson ASG-21 fire control system. Ammunition supply was 1,242 rounds. The B-52H went on to utilize cruise missiles (the Skybolt missile was eventually cancelled before production), anti-ship missiles and unmanned drones in this fashion thanks to its heavy duty wing pylons. Light duty pylons were added later between the two engine pods on either wings and retrofitted to earlier H- and G-models. Like her G-model sisters, B-52H’s were cleared to use 20 x AGM-69 SRAM nuclear missiles beginning in 1971. Low-level operations became another improvement of this model type. The last of 102 B 52H bombers was delivered in 1963, bringing production to 744. The B 52H has the much more powerful TF33 engine, eliminating water injection and instead of four 12.7 mm (0.5 in) tail guns has a six barrel cannon. Surviving B 52Gs and B 52Hs are continually being fitted with updated systems for service into the second half of the 1980s.

Over a three-year period to 1963, the USAF spent $825 million on B-52 rework.

A total of 99 B-52Gs, carrying 12 external AGM-86B air-launched cruise missiles (ALCM), and 96 B-52Hs with 12 external and, later, eight internal ALCMs, were to be operational by 1990. The B-52Hs were to receive internally mounted common strategic rotary launchers (CSRL) in the late 1980s to carry the ALCMs, SRAMS, advanced cruise missiles, and free-fall nuclear weapons. The first ALCM equipped B-52G unit became operational in December 1982. Cruise-missile-carrying B-52Gs are being fitted with a strakelet fairing at the wing root leading edge for indentification purposes under the unratified SALT II agreement.

Most of the early B-52s were phased out by 1970, due to Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara’s mid-sixties decision to decrease the strategic bomber force.

Numerous B-52s were rebuilt with a ‘Big Belly’ to carry 84 bombs inside, plus 24 on triple tandem pylons under the wings. Modified B-52Ds, referred to as Big Belly, dropped aerial mines in the North Vietnamese harbors and river inlets in May 1972. In December of the same year, B-52Ds and B-52Gs began to bomb military targets in the Hanoi and Haiphong areas of North Vietnam.

A total of 744 were built between 1954 and 1962, including the XB-52 and YB-52 test models. During its peak involvement with Strategic Air Command, no fewer than 650 B-52 bombers made up 42 SAC bomber squadrons at 38 bases. In 2010, the Air Force maintains approximately 76 active and 20 reserve B-52’s from the 744 total that were produced. Production of all B-52’s lasted from 1952 through 1962 and handled at the Boeing Seattle, Washington and Wichita, Kansas plants.

A world air speed record was set on September 26th, 1958, in a B-52D reaching 560.705 miles per hour on a closed circuit covering 6,210 miles. The same day netted another air speed record of 597.675 miles per hour over a 3,105 mile course. On December 14th, 1960, a B-52G set a world air distance record by traveling 10,078.84 miles without refueling. This record was bested several years later on January 10th/11th, 1962, when a B-52H achieved 12,532.28 miles of unrefueled flight time in a journey from Japan to Spain. According to Boeing, this single flight alone broke some 11 speed and distance records.

The B-52 has also made it into pop culture as it was the aircraft featured in the 1964 Stanley Kubrick film “Dr Strangelove”.

Prototype

MTOW: 177 tonne

B-52A

Long-range heavy bomber.

Engines: 8 x Pratt & Whitney J57-P-3 turbojets, 10,000 lb thrust

Wingspan: 185 ft

Lenght: 156 ft

Wing area: 4000 sq.ft

Loaded weight: approx. 400,000 lb.

Max speed: approx. 650 m.p.h.

Ceiling: 50,000 ft.

Typical range: 6,000 miles with 25,000 lb bombs

Armament; 4 x.50 in. machine-guns in tail-turret.

RB-52B

Engines: 8 x Pratt & Whitney J57-P-3, 9700 lb

Wingspan: 185 ft

Length: 156 ft 6 in

Height: 48 ft 3.5 in

Wing area: 4000 sq.ft

Empty weight: 175,000 lb

Loaded weight: 350,000 lb

Max speed: 630 mph

Service ceiling: 50,000 ft

Normal range: 3000 mi (with 75,000 lb bombload)

Max range: 6000 mi (with 25,000 lb bombload)

Armament: 2 x 20mm tail gun

B-52D

Engines: 8 x Pratt & Whitney J57-P-29WA turbojet, 12,100 lb thrust.

Armament: 4 x .50in mg.

Bomb load: 27216 kg (60,000 lb).

Range: 7400 sm / 11,860 km

B-52G

Engines: 8 x Pratt & Whitney J57-P-43W turbojet, 11,200 lb, 49835 N thrust.

Wing span: 185 ft 0 in (56.39 m).

Wing area: 4000 sq.ft

Length: 157 ft 7 in (48.03 m).

Height: 40 ft 8 in (12.4 m).

Armament: 4 x .50in mg.

Max TO wt: 480,000 lb (217,720 kg).

Max level speed: 660 mph (1062 kph) at 20,000 ft

Range: 6480 nm / 12000 km

Armament: 4x MG 12,7mm

Bombload: 22680kg

B-52H

Engines: eight Pratt & Whitney TF33-P-3/103 turbofans, 75.62 kN (17,000 lb st)

Length 49.05m (160 ft 11 in)

Height: 12.40m (40 ft 8 in)

Wing span: 56.39m (185 ft 0 in)

Wing area: 371.6 sq.m (4,000.0 sq ft).

Empty weight: 83,250 kg (185,000 lb)

Max Take-Off Weight: 229,088 kg (505,000 lb)

Fuel capacity: 312,197 lb (141,610 kg), 47,975 U.S. gal (181,610 L)

After inflight refuelling weight: 256738 kg (566,000 lb).

Maximum speed Mach: 0.86, 1045 km/h (650 mph)

Cruising speed high altitude: Mach 0.77, 819 km/h (509 mph)

Penetration speed low altitude: 652-676 km/h (405-420 mph)

Service ceiling: 16,765m (55,000 ft)

Combat ceiling: 14326 m (47,000 ft).

Range at high altitude with bombload: 16300 km (10,130 miles).

Armament: up to 22,680 kg (50,000 lb) of ordnance, one Vulcan T 171 six barrel radar-directed 20mm cannon

Crew: 6

102 built.