USS Shenandoah was the first of four United States Navy rigid airships. The design was based on Zeppelin bomber L-49 (LZ-96), built in 1917 which had been forced down intact in France in October, 1917 and carefully studied. L-49 was a lightened Type U “height climber”, designed for altitude at the expense of other qualities.

The L-49 was one of the “height climbers” designed by the Germans late in World War I, when improvements in Allied fighter aircraft and anti-aircraft artillery made it necessary for Zeppelins to climb to great altitudes to avoid being shot down. For the Zepeplins to rise to greater heights on a fixed volume of lifting gas, however, the weight and strength of their structures were dramatically reduced. This decrease in strength was accepted as a wartime necessity, since a structurally weaker Zeppelin flying above the reach of enemy aircraft and artillery was safer than a stronger Zeppelin that could be easily attacked.

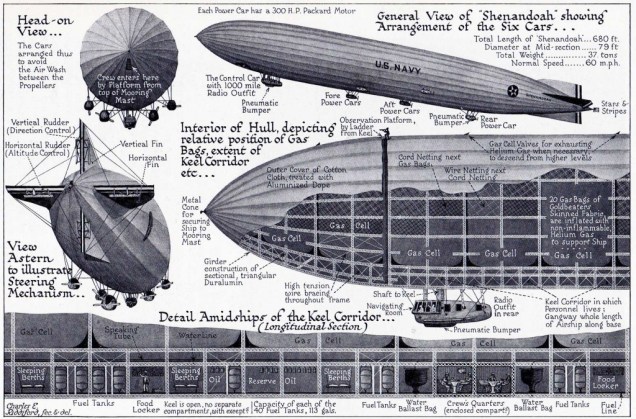

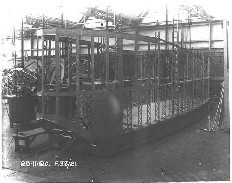

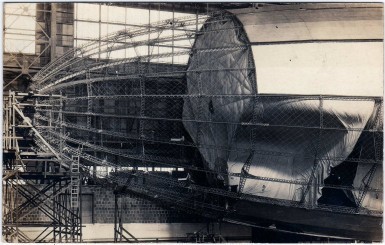

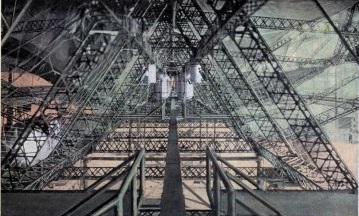

The design was found insufficient and a number of the features of newer Zeppelins were used, as well as some structural improvements. The structure was built from a new alloy of aluminum and copper known as duralumin. Girders were fabricated at the Naval Aircraft Factory. Whether the changes introduced into the original design of L-49 played a part in Shenandoah’s later breakup is a matter of debate. An outer cover of high-quality cotton cloth was sewn, laced or taped to the duralumin frame and painted with aluminum dope.

The gas cells were made of goldbeater’s skins, one of the most gas-impervious materials known at the time. Named for their use in beating and separating gold leaf, goldbeater’s skins were made from the outer membrane of the large intestines of cattle. The membranes were washed and scraped to remove fat and dirt, and then placed in a solution of water and glycerine in preparation for application to the rubberized cotton fabric providing the strength of the gas cells. The membranes were wrung out by hand to remove the water-glycerine storage solution and then rubber-cemented to the cotton fabric and finally given a light coat of varnish. The 20 gas cells within the airframe were filled to about 85% of capacity at normal barometric pressure. Each gas cell had a spring-loaded relief valve and manual valves operated from the control car.

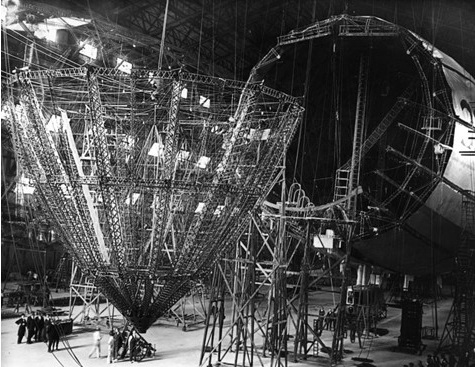

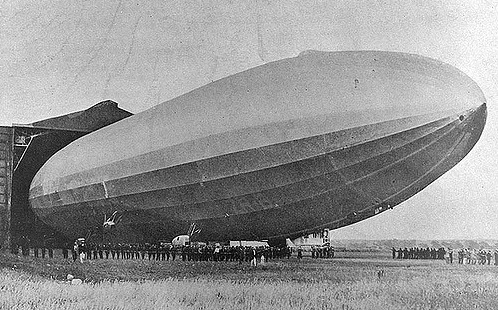

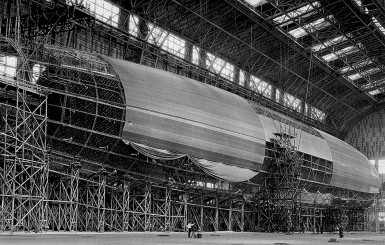

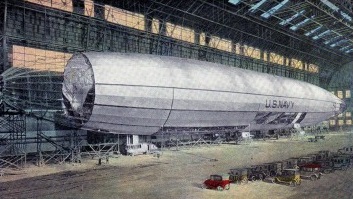

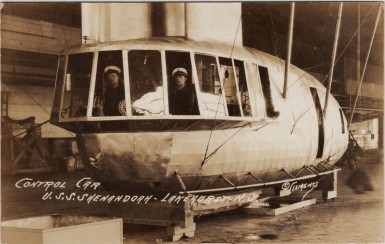

Shenandoah was originally designated FA-1, for “Fleet Airship Number One” but this was changed to ZR-1. The airship was 680 ft (207.26 m) long and weighed 36 tons (32658 kg). It had a range of 5,000 mi (4,300 nmi; 8,000 km), and could reach speeds of 70 mph (61 kn; 110 km/h). Shenandoah was assembled at Naval Air Station Lakehurst, New Jersey in 1922–1923, in Hangar No. 1, the only hangar large enough to accommodate the ship; its parts were fabricated at the Naval Aircraft Factory in Philadelphia. NAS Lakehurst had served as a base for Navy blimps for some time, but Shenandoah was the first rigid airship to join the fleet.

Like all previous zeppelins, ZR-1 had been designed on the assumption that the ship would be operated with hydrogen, but the fiery crash of the U.S. Army airship Roma in 1922 convinced the U.S. government to operate future airship’s with helium, despite the high cost and very limited supply of the gas.

As the first rigid airship to use helium rather than hydrogen, Shenandoah had a significant edge in safety over previous airships. Helium was relatively scarce at the time, and the Shenandoah used much of the world’s reserves just to fill its 2,100,000 cubic feet (59,000 cu.m) volume. Los Angeles—the next rigid airship to enter Navy service, originally built by Luftschiffbau Zeppelin in Germany as LZ 126—was at first filled with the helium from Shenandoah until more could be procured.

Shenandoah was powered by 300 hp (220 kW), eight-cylinder Packard gasoline engines. Six engines were originally installed, but in 1924 one engine (aft of the control car) was removed. The first frame of Shenandoah was erected by 24 June 1922; on 20 August 1923, the completed airship was floated free of the ground. Helium cost $55 per thousand cubic feet at the time, and was considered too expensive to simply vent to the atmosphere to compensate for the weight of fuel consumed by the gasoline engines. Neutral buoyancy was preserved by installing condensers to capture the water vapor in the engine exhaust. The need to preserve helium had many operational implications, including the timing of flights to coordinate with changes in ambient temperature.

The Navy also had to learn how to use helium to operate a large rigid airship, which had never previously been attempted. The need to conserve the expensive and scarce lifting gas required flight operations which differed considerably from the techniques which had been developed for operating airships inflated with easily-replaced hydrogen. For example, while the Germans typically began a zeppelin flight with gas cells inflated to 100% capacity, and then valved hydrogen (either manually or automatically) as the ship rose, the Americans — unable to afford the loss of precious helium — had to operate with lower inflation levels, and therefore less lift, and had to be more careful about valving gas to descend or to maintain aerostatic equilibrium.

Shenandoah first flew on 4 September 1923. ZR-1 made a series of test and demonstration flights in September and early October, 1923 — including an appearance at the National Air Races in St. Louis and flights over New York and Washington.

It was christened on 10 October 1923 by Mrs. Edwin Denby, wife of the Secretary of the Navy, and commissioned on the same day with Commander Frank R. McCrary in command. Mrs. Denby named the airship after her home in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, and the word shenandoah was then believed to be a Native American word meaning “daughter of stars”.

Shenandoah was designed for fleet reconnaissance work of the type carried out by German naval airships in World War I. Her precommissioning trials included long-range flights during September and early October 1923, to test her airworthiness in rain, fog and poor visibility. On 27 October, Shenandoah celebrated Navy Day with a flight down the Shenandoah Valley and returned to Lakehurst that night by way of Washington and Baltimore, where crowds gathered to see the new airship in the beams of searchlights.

At this time, Rear Admiral William A. Moffett—Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics and staunch advocate of the airship—was discussing the possibility of using Shenandoah to explore the Arctic. He felt such a program would produce valuable weather data, as well as experience in cold-weather operations. With its endurance and ability to fly at low speeds, the airship was thought to be well-suited to such work. President Calvin Coolidge approved Moffett’s proposal, but Shenandoah’s upper tail fin covering ripped during a gale on 16 January 1924, and the sudden roll tore her away from the Lakehurst mast, ripping out her mooring winches, deflating the first helium cell and puncturing the second. Zeppelin test pilot Anton Heinen rode out the storm for several hours and landed safely while the airship was being blown backwards. Extensive repairs were needed, and the Arctic expedition was scrapped.

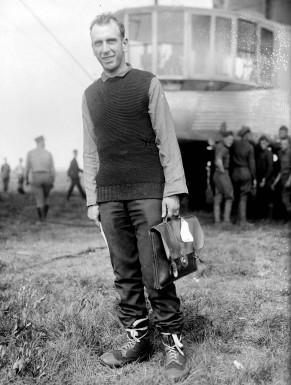

On February 12, 1924, while it was undergoing repairs, Shenandoah received a new commanding officer, Lt. Cdr. Zachary Lansdowne.

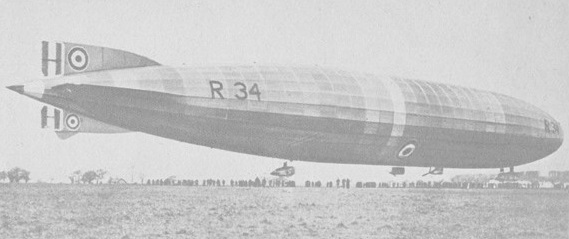

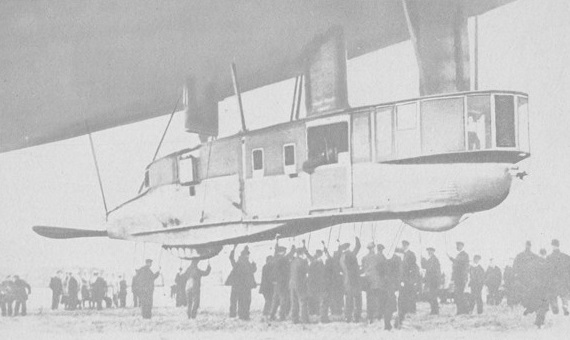

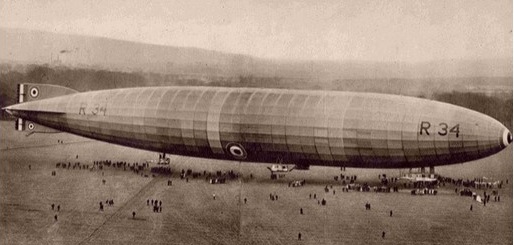

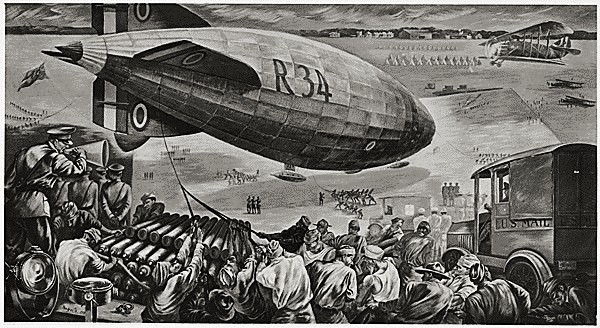

Lansdown, a 1909 graduate of the United States Naval Academy, was one of the Navy’s first officers trained in lighter-than-air aviation. He trained with the crew of the British airship R-34, and became the first American to cross the Atlantic nonstop by air as the American naval observer aboard R-34’s 1919 transatlantic flight. After service as a White House aide, Lansdowne was the Assistant Naval Attache in Germany in 1922-1923, where was involved with the negotiations for the construction of the LZ-126, which became the ZR-3 USS Los Angeles.

The ship was grounded for repairs until May 22, 1924, when it was returned to service with reinforcements to its mooring assembly, nose, and fins. The sixth engine in its control car was also removed and replaced with radio equipment, including a long distance direction finding set.

Shenandoah’s repairs were completed in May, and the summer of 1924 was devoted to work with its engines and radio equipment to prepare for fleet duty. In August 1924 it reported for duty with the Scouting Fleet and took part in tactical exercises. Shenandoah succeeded in discovering the “enemy” force as planned but lost contact with it in foul weather. Technical difficulties and lack of support facilities in the fleet forced it to depart the operating area ahead of time to return to Lakehurst. Although this marred the exercises as far as airship reconnaissance went, it emphasized the need for advanced bases and maintenance ships if lighter-than-air craft were to take any part in operations of this kind.

In July 1924, the oiler Patoka put in at Norfolk Naval Shipyard for extensive modifications to become the Navy’s first airship tender. An experimental mooring mast 125 ft (38 m) above the water was constructed; additional accommodations both for the crew of Shenandoah and for the men who would handle and supply the airship were added; facilities for the helium, gasoline, and other supplies necessary for Shenandoah were built, as well as handling and stowage facilities for three seaplanes. Lansdowne conducted pioneering operations in which he moored Shenandoah to a mast installed on the support ship Patoka, to show the possibility of underway replenishment and supply to extend the ship’s range and allow an airship to work closely with the fleet, and Lansdowne conducted operations with surface ships such as the battleship USS Texas whenever possible. The first successful mooring was made on 8 August. During October 1924, Shenandoah flew from Lakehurst to California and on to Washington State to test newly erected mooring masts. This was the first flight of a rigid airship across North America.

1925 began with nearly six months of maintenance and ground test work. Shenandoah did not take to the air until 26 June, when it began preparations for summer operations with the fleet. In July and August, it again operated with the Scouting Fleet, successfully performing scouting tasks and being towed by Patoka while moored to that ship’s mast.

Shenandoah made one of its most impressive demonstrations in October, 1924, when the ship made a difficult 19-day journey across the United States from Lakehurst to San Diego, via Forth Worth, and then traveled up the west coast to Seattle and back to San Diego, before returning to Lakehurst via Fort Worth. Shenandoah logged 235 flight hours on its headline-making journey across the country, and captured the enthusiasm of both the American public and also leaders in the field of aviation around the world.

Upon Shenandoah’s return to Lakehurst the ship was was deflated so that its helium could be transferred to the newly arrived ZR-3 (soon to be commissioned USS Los Angeles) which had just been delivered to Lakehurst by Hugo Eckener and his German crew; the supply of helium was so scare in 1924 that the United States did not have enough of the gas to inflate two large airships at the same time.

During Shenandoah’s lay-up, Zachary Lansdowne made a decision which would later be highly controversial. In order to limit the loss of helium by leakage through the automatic valves, and to eliminate several hundred pounds of weight, Lansdowne ordered the removal of 10 of the ship’s 18 automatic gas valves. These valves automatically released helium when as the ship climbed, to avoid over-expansion of the cells at higher altitude, which could damage both the cells themselves and the surrounding framework. Lansdowne’s modification limited the amount of gas that could be valved in a given time, and meant that Shenandoah’s valves could not keep up with an increase of altitude greater than 400 feet per minute; at any higher rate of climb, the ship could not release enough helium to keep up with the expansion of the gas cells.

On 2 September 1925, Shenandoah departed Lakehurst on a promotional flight to the Midwest that would include flyovers of 40 cities and visits to state fairs. Testing of a new mooring mast at Dearborn, Michigan, was included in the schedule. While passing through an area of thunderstorms and turbulence over Ohio early in the morning of 3 September, during its 57th flight, the airship was caught in a violent updraft exceeding 1,000 feet per minute that carried it beyond the pressure limits of its gas bags to an altitude over 6,000 feet. Twisted by the storm, and the ship finally suffered catastrophic structural failure, breaking in two at frame 125, approximately 220 feet from the bow. The aft section sank rapidly, breaking up further, with two of the engine cars breaking away and falling to the ground. It crashed in several pieces near Caldwell, Ohio. Fourteen crew members, including Commander Zachary Lansdowne, were killed. This included every member of the crew of the control cabin (except for Lieutenant Anderson, who escaped before it detached from the ship); two men who fell through holes in the hull; and several mechanics who fell with the engines.

There were twenty-nine survivors, who succeeded in riding three sections of the airship to earth. The largest group was eighteen men who made it out of the stern after it rolled into a valley. Four others survived a crash landing of the central section. The remaining seven were in the bow section which Commander (later Vice Admiral) Charles E. Rosendahl navigated as a free balloon. In this group was Anderson who—until he was roped in by the others—straddled the catwalk over a hole. Without the weight of the control car, the bow section, with seven men aboard, including Navigator Charles Rosendahl, ascended rapidly. Under Rosendahl’s leadership, the men in the bow valved helium from the cells and free-ballooned the bow to a relatively gentle landing.

The Shenandoah Crash Sites are located in the hillsides of Noble County. Site No. 1, in Buffalo Township, surrounded the Gamary farmhouse, which lay beneath the initial break-up. An early fieldstone and a second, recent granite marker identify where Commander Lansdowne’s body was found. Site No. 2 (where the stern came to rest) is a half-mile southwest of Site No. 1 across Interstate 77 in Noble Township. The rough outline of the stern is marked with a series of concrete blocks, and a sign marking the site is visible from the freeway. Site No. 3 is approximately six miles southwest in Sharon Township at the northern edge of State Route 78 on the part of the old Nichols farm where the nose of the Shenandoah’s bow was secured to trees. Although the trees have been cut down, a semi-circular gravel drive surrounds their stumps and a small granite marker commemorates the crash. The Nichols house was later destroyed by fire.

The crash site attracted thousands of visitors in its first few days. Within five hours of the crash more than a thousand people had arrived to strip the hulk of anything they could carry. On Saturday, 5 September 1925, the St. Petersburg Times of Florida reported that the site of the crash had quickly been looted by locals, describing the frame as being “[laid] carrion to the whims of souvenir seekers”. Among the items believed to have been taken were the vessel’s logbook and its barograph, both of which were considered critical to understanding how the crash had happened. Also looted were many of the ship’s 20 deflated silken gas cells, each worth several thousand dollars, most of them unbroken but ripped from the framework before the arrival of armed military personnel. Looting was so extensive that it was initially believed even the bodies of the dead had been stripped of their personal effects, and that operatives from the Department of Justice were being sent to investigate. That this was happening was soon denied by those publicly involved in the incident, however. Still, a local farmer on whose property part of the vessel’s wreckage lay began charging the throngs of visitors to enter the crash site at a rate of $1 (equivalent to about $13.60 in 2015) for each automobile and 25¢ per pedestrian as well as 10¢ for a drink of water.

On 17 September the Milwaukee Sentinel reported that 20 Department of Justice operatives had indeed been summoned to the site and that they along with an unspecified number of federal and state prohibition agents had visited private homes to collect four truck loads of wreckage along with personal grips of several crew members and a cap believed to have belonged to Commander Lansdowne. Lansdowne’s Annapolis class ring had also been thought to have been taken from his hand by looters as it was not then recovered-it was found by chance in June 1937 near the crash site # 1. No one was charged with any crime.

Two schools of thought developed about the cause of the crash. One theory is that the gas cells over-expanded as the ship rose, due to Lansdowne’s decision to remove the 10 automatic release valves, and that the expanding cells damaged the framework of the airship and led to its structural failure.

Official inquiry brought to light the fact that the fatal flight had been made under protest by Commander Lansdowne (a native of Greenville, Ohio), who had warned the Navy Department of the violent weather conditions that were common to that area of Ohio in late summer. His pleas for a cancellation of the flight only caused a temporary postponement: his superiors were keen to publicize airship technology and justify the huge cost of the airship to the taxpayers. So, as Lansdowne’s widow consistently maintained at the inquiry, publicity rather than prudence won the day. This event was the trigger for Army Colonel Billy Mitchell to heavily criticize the leadership of both the Army and the Navy, leading directly to his court-martial for insubordination and the end of his military career. Heinen, according to the Daily Telegraph, placed the mechanical fault for the disaster on the removal of eight of the craft’s 18 safety valves, saying that without them he would not have flown on her “for a million dollars”. These valves had been removed in order to better preserve the vessel’s helium, which at that time was considered a limited global resource of great rarity and strategic military importance; without these valves, the helium contained in the rising gas bags had expanded too quickly for the bags’ valves’ design capacity, causing the bags to tear apart the hull as they ruptured (of course, the helium which had been contained in these bags became lost into the upper atmosphere).

After the disaster, airship hulls were strengthened, control cabins were built into the keels rather than suspended from cables, and engine power was increased. More attention was also paid to weather forecasting.

Several memorials remain near the crash site. There is another memorial at Moffett Field, California, and a small private museum in Ava, Ohio.

ZR-1 USS Shenandoah

Length: 680 feet

Diameter: 79 feet

Gas capacity: 2,115,000 cubic feet

Useful lift: 48,774 lbs

Maximum speed: 58 knots

Crew: 40 officers and men

First flight: September 4, 1923

Crashed: September 2-3, 1925

Total flight hours: 740:09