Allen first announced the Stratolaunch in 2011. Being the largest aeroplane in the world, it’s intended to fly into low Earth orbit and launch an Orbital ATK’s Pegasus XL rocket into space. The rocket is designed to carry small satellites that weigh up to 454kg into orbit. Once the Stratolaunch hits an altitude of 10,668m, the rocket that’s tethered to its belly will finish out the journey. If Allen’s full ambitions are realised, the company will be able to send crewed missions into space at a lower price than Russia is charging NASA.

Stratolaunch is designed to carry up to three Pegasus XL air launch vehicles, each capable of hauling a 1,000-pound satellite into low Earth orbit. The company says it’s looking into medium and large, solid and liquid fueled launch vehicles, which would boost the size of satellites they could carry.

Test flights were supposed to begin in 2016, but that deadline came and went. Aerospace engineer Burt Rutan and his team were at work on the massive aeroplane all this time.

This is a first-of-its-kind aircraft, so the aircraft was to start testing at the Mojave Air and Space Port with plans for a launch demonstration in 2019. The plane is the largest in the world based on wingspan, measuring 385 feet.

The Scaled Composites Model 351 Stratolaunch is an aircraft built for Stratolaunch Systems by Scaled Composites to carry air-launch-to-orbit rockets. In early 2011, Dynetics began studying the project and had approximately 40 employees working on it at the December 2011 public announcement.

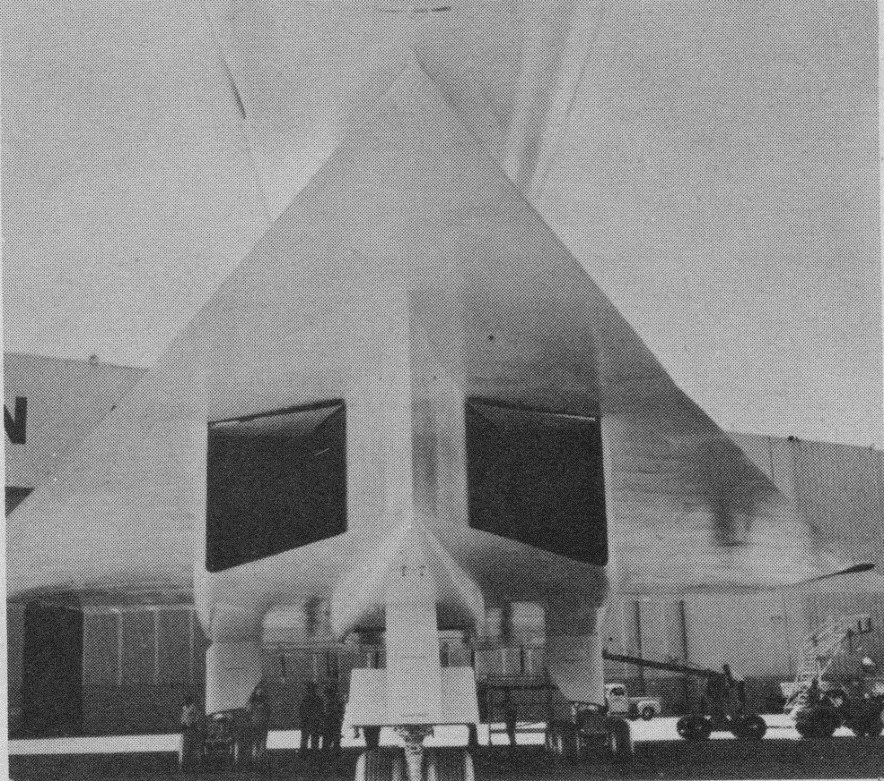

In May 2012, its specially constructed hangar was being built at the Mojave Air and Space Port in Mojave, California. In October 2012, the first of two manufacturing buildings, a 88,000 sq ft (8,200 m2) facility for construction of the composite sections of the wing and fuselage, was opened for production.

By June 2016 Scaled Composites had 300 people working on the project. By May 1, 2017, Stratolaunch had already spent hundreds of millions of dollars on the project. On May 31, 2017, the aircraft was rolled out for fueling tests, and to be prepared for ground testing, engine runs, taxi tests, and ultimately first flight.

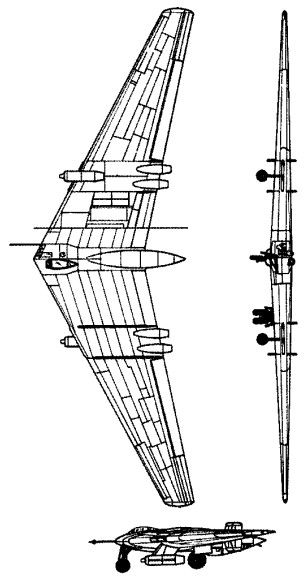

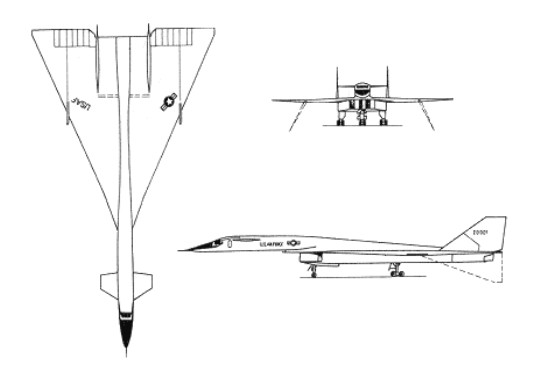

Stratolaunch has a twin-fuselage configuration, each 238 ft (73 m) long and supported by 12 main landing gear wheels and two nose gear wheels, for a total of 28 wheels. Each fuselage has its own empennage and the twin fuselages are 95 feet apart.

The pilot, co-pilot and flight engineer are accommodated in the right fuselage cockpit. The flight data systems are in the left fuselage. The unpressurized left fuselage cockpit is unmanned with storage space for up to 2,500lb of mission specific support equipment. Both fuselage cockpits are pressurized and separated by a composite pressure bulkhead from the remainder of the unpressurized vehicle.

At 385 ft (117 m), it is the largest plane by wingspan, surpassing the Hughes H-4 Hercules flying boat of 321 feet (98 m). The main center section is made up of four primary composite spars supported by four secondary spars. The center section of the high-mounted, high aspect ratio wing is fitted with a Mating and Integration System (MIS), developed by Dynetics and capable of handling a 490,000 lb (220 t) load. The wing houses six main and two auxiliary fuel tanks, with the main tanks located inboard adjacent to an engine. The auxiliary tanks are located in the inboard wing where the load-carrying structure joins the fuselage.

Stratolaunch is powered by six Pratt & Whitney PW4056 engines positioned on pylons outboard of each fuselage, providing 56,750 lbf (252.4 kN) of thrust per engine. Many of the aircraft systems have been adopted from the Boeing 747-400, including the engines, avionics, flight deck, landing gear and other systems, reducing development costs.

The flight controls include 12 cable-driven ailerons powered by hydraulic actuators, split rudders, and horizontal stabilizers on twin tail units. The wing has 14 electrically signaled, hydraulically actuated trailing-edge split flaps that also act as speed brakes. The hydraulic system and actuators, electrical system, avionics, pilot controls, and flight deck are from donor B747-400s. Approximately 250,000 lb of the aircraft’s takeoff weight of 1,300,000 lb is from B747-400 components. Much of the design is based on the Boeing 747-400, replicating much of the avionics, engineering, power plants, and more to reduce the $400 million cost of the project.

Within Scaled Composites, its model number is M351. It is nicknamed “Roc” after Sinbad’s Roc, the mythical bird so big it could carry an elephant.

Initially, flights will be under an experimental certification from the FAA.

The Stratolaunch has a wingspan of 117m, it uses six 747 jet engines, sits on 28 wheels, can carry 113,400kg of fuel, and weighs 226,800kg without fuel. In order to take off, it needs about 3660m of runway.

The Stratolaunch is intended to carry a 550,000-pound (250 t) payload and has a 1,300,000-pound (590 t) maximum takeoff weight.

In December 2017, registration N351SL first low-speed taxi test took it to 25 knots (46 km/h) on the runway powered by its six turbofans to test its steering, braking, and telemetry. Higher-speed taxi tests began in 2018, reaching 40 knots (74 km/h) in February, and 78 kn (140 km/h) in October. On January 9, 2019, Stratolaunch completed a 110 knot (219 km/h) taxi test, and released a photograph of the nose landing gear lifted off the ground during the test.

In January 2019, three months after the death of Stratolaunch founder and Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, Stratolaunch abandoned the development of its PGA rocket engines and dedicated launchers. Stratolaunch was then reported to be aiming for a first flight within a few weeks and a first launch from the carrier in 2020.

The aircraft first flew on April 13, 2019 at 06:58, at the Mojave Air and Space Port, reaching 17,000 ft (5,200 m) and 165 kn (305 km/h) in a 2 h 29 min flight. Tests included various flight control manoeuvres to calibrate speed and evaluate flight-control systems, including roll doublets, yawing manoeuvres, pushovers and pull-ups, and steady heading sideslips. Test crew Evan Thomas and Chris Guarente also flew simulated landing approach exercises at an altitude of 15,000ft.

The company ceased operations the next month, and placed all company assets, including the aircraft, for sale for US$400 million by June 2019. Cerberus Capital Management acquired Stratolaunch Systems including the Stratolaunch aircraft in October 2019. Stratolaunch announced in December 2019 that it would now be focusing on offering high-speed flight test services.

So far, only one flight has been carried out.

Model 351 Stratolaunch

Powerplant: 6 × Pratt & Whitney PW4056 turbofan, 56,750 lbf (252.4 kN) thrust each

Wingspan: 385 ft (117 m)

Length: 238 ft (73 m)

Height: 50 ft (15 m)

Empty weight: 500,000 lb (226,796 kg)

Gross weight: 750,000 lb (340,194 kg) with no external payload

Max takeoff weight: 1,300,000 lb (589,670 kg)

External payload: 550,000 lb (250,000 kg)

Maximum speed: 460 kn (530 mph, 850 km/h)

Range: 1,000 nmi (1,200 mi, 1,900 km) radius

Ferry range: 2,500 nmi (2,900 mi, 4,600 km)