Intended as a long-range flying-boat with a heavy armament, and much bigger than Short Sunderland. The first of two prototypes flew in 1944. The second prototype would have been a 40-passenger aircraft but was cancelled due to low demand.

Intended as a long-range flying-boat with a heavy armament, and much bigger than Short Sunderland. The first of two prototypes flew in 1944. The second prototype would have been a 40-passenger aircraft but was cancelled due to low demand.

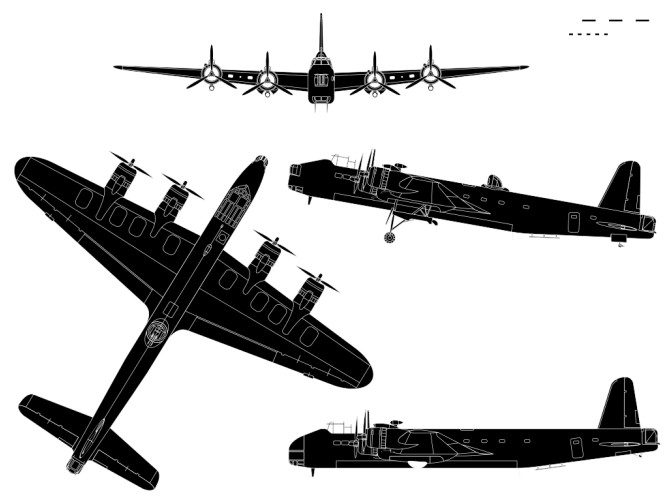

In 1936 the RAF also decided to investigate the feasibility of the four-engined bomber. The Air Ministry Specification B.12/36 had several requirements. The bomb load was to be a maximum of 14,000 lb (6,350 kg) carried to a range of 2,000 miles (3218 km) or a lesser payload of 8,000 lb (3,629 kg) to 3,000 miles (4,800 km) (incredibly demanding for the era). It had to cruise at 230 or more mph at 15,000 ft (4,600 m) and have three gun turrets (in nose, amidships and rear) for defence. The aircraft should also be able to be used as a troop transport for 24 soldiers, and be able to use catapult assistance for takeoff. The idea was that it would fly troops to far corners of the British Empire and then support them with bombing. To help with this task as well as ease production, it needed to be able to be broken down into parts, for transport by train. Since it could be operating from limited “back country” airfields, it needed to lift off from a 500 ft (150 m) runway and able to clear 50 ft (15 m) trees at the end, a specification most small aircraft would have a problem with today.

Initially left out of those asked to tender designs, Shorts were included because they already had similar designs in hand and they had ample design staff and production facilities. Shorts were producing several four-engined flying boat designs of the required size and created their S.29 by removing the lower deck and boat hull of the S.25 Sunderland. The new S.29 design was largely identical otherwise: the wings and controls were the same, construction was identical and it even retained the slight upward bend at the rear of the fuselage, originally intended to keep the Sunderland’s tail clear of sea spray.

In October 1936, the S.29 was low down on the shortlist of designs considered and the Supermarine Type 317 was ordered in prototype form in January 1937. However it was decided that an alternative design to Supermarine was needed for insurance and that Shorts should build it as they had experience with four-engined aircraft. The original design had been criticized when considered and in February 1937 the Air Ministry suggested modifications to the original Short design, including considering the use of the Bristol Hercules engine as an alternative to the Napier Dagger, increasing service ceiling (28,000 ft) and reducing the wingspan. Shorts accepted this large amount of redesign. The project had added importance due to the death of Supermarine’s designer causing doubt in the Air Ministry. The S.29 used the Sunderland’s 114 ft (35 m) wing and it had to be reduced to less than 100 ft (30 m), the same limit as that imposed on the P.13/36 designs (Handley Page Halifax and Avro Manchester). In order to get the needed lift from a shorter span and excess weight, the redesigned wing was thickened and reshaped. It is often said that the wingspan was limited to 100 ft so the aircraft would fit into existing hangars. “The wing span was limited by the Air Ministry to 100 ft” but the maximum hangar opening was 112 ft (34 m) and the specification required outdoor servicing. The limitation was to force the designer to keep overall weight down.

In June the S.29 was accepted as the second string for the Supermarine 316 and formally ordered in October. After receiving orders for two prototypes and 100 production aircraft to the S.29 design which became the Short Stirling, Shorts built in 1938 a 1/2-scale prototype at its own expense. Powered by four 90hp Pobjoy Niagara III engines, this Short S.31 (also known internally as the M4 – the title on the tailfin) was mostly of wooden construction apart from a semi-monocoque fuselage, and seated two in tandem. In overall silver finish and marked M4, the Short S.31 flew on September 19, 1938, at Rochester, piloted by Shorts’ Chief Test Pilot J. Lankester Parker.

The takeoff run was thought to be too long, and fixing this required the angle of the wing to be increased for takeoff, normally meaning the aircraft would be flying nose down while cruising (as in the Armstrong Whitworth Whitley). Short had originally decided on an incidence of 3° giving the best possible cruise performance, but the RAF asked that the incidence be increased to 6.5°, being more concerned with improving take-off performance than the cruising speed. In order to accommodate the RAF request for increased wing incidence a major re-design of the central fuselage would have normally be undertaken, but because of time restraints, Short decided on a “quick fix” by lengthening the main landing gear legs to give a higher ground angle. At the end of 1938, this change was incorporated on the Short S.31 prototype.

The single stage landing gear leg was discarded due to the increased length of the undercarriage rods which proved too long to be retracted into the engine nacelle wheel wells. A two stage undercarriage was built which retracted vertically and then backwards into the nacelle. The undercarriage retraction motors were originally located inside the nacelle, but were later relocated inside the fuselage to allow for manual retraction in the event of motor failure.

Other changes included the installation of four 115 hp (86 kW) Pobjoy Niagara IV radial engines in January 1939. In order to address longitudinal control problems horn-balanced elevators were installed but these were soon replaced by a larger tailplane with conventional elevators in March 1939.

In 1940, now in green/brown camouflage with yellow undersides, the Short S.31 was fitted with Va-scale mock-ups of the Boulton Paul Type O ventral and Type H dorsal twin-cannon turrets proposed for a version of the Stirling II, and was tested in the RAE 7.3m wind tunnel. Further flights were made from March 13, 1942, onwards (with a shortened u/c), and the Short S.31 was scrapped after a takeoff accident at Stradishall in February 1944.

Max take-off weight: 2586 kg / 5701 lb

Wingspan: 15.09 m / 50 ft 6 in

Length: 13.31 m / 44 ft 8 in

Max. speed: 290 km/h / 180 mph

In 1936 the RAF also decided to investigate the feasibility of the four-engined bomber. The Air Ministry Specification B.12/36 had several requirements. The bomb load was to be a maximum of 14,000 lb (6,350 kg) carried to a range of 2,000 miles (3218 km) or a lesser payload of 8,000 lb (3,629 kg) to 3,000 miles (4,800 km) (incredibly demanding for the era). It had to cruise at 230 or more mph at 15,000 ft (4,600 m) and have three gun turrets (in nose, amidships and rear) for defence. The aircraft should also be able to be used as a troop transport for 24 soldiers, and be able to use catapult assistance for takeoff. The idea was that it would fly troops to far corners of the British Empire and then support them with bombing. To help with this task as well as ease production, it needed to be able to be broken down into parts, for transport by train. Since it could be operating from limited “back country” airfields, it needed to lift off from a 500 ft (150 m) runway and able to clear 50 ft (15 m) trees at the end, a specification most small aircraft would have a problem with today.

Initially left out of those asked to tender designs, Shorts were included because they already had similar designs in hand and they had ample design staff and production facilities. Shorts were producing several four-engined flying boat designs of the required size and created their S.29 by removing the lower deck and boat hull of the S.25 Sunderland. The new S.29 design was largely identical otherwise: the wings and controls were the same, construction was identical and it even retained the slight upward bend at the rear of the fuselage, originally intended to keep the Sunderland’s tail clear of sea spray.

In October 1936, the S.29 was low down on the shortlist of designs considered and the Supermarine Type 317 was ordered in prototype form in January 1937. However it was decided that an alternative design to Supermarine was needed for insurance and that Shorts should build it as they had experience with four-engined aircraft. The original design had been criticized when considered and in February 1937 the Air Ministry suggested modifications to the original Short design, including considering the use of the Bristol Hercules engine as an alternative to the Napier Dagger, increasing service ceiling (28,000 ft) and reducing the wingspan. Shorts accepted this large amount of redesign. The project had added importance due to the death of Supermarine’s designer causing doubt in the Air Ministry. The S.29 used the Sunderland’s 114 ft (35 m) wing and it had to be reduced to less than 100 ft (30 m), the same limit as that imposed on the P.13/36 designs (Handley Page Halifax and Avro Manchester). In order to get the needed lift from a shorter span and excess weight, the redesigned wing was thickened and reshaped. It is often said that the wingspan was limited to 100 ft so the aircraft would fit into existing hangars. “The wing span was limited by the Air Ministry to 100 ft” but the maximum hangar opening was 112 ft (34 m) and the specification required outdoor servicing. The limitation was to force the designer to keep overall weight down.

The original layout of the bomber was tried out by the construction of a half-scale model S.31 fitted with four 97kW Pobjoy engines. Flying trials with this proved the feasibility of the design. Short had originally decided on an incidence of 3° giving the best possible cruise performance, but the RAF asked that the incidence be increased to 6.5°, being more concerned with improving take-off performance than the cruising speed. In order to accommodate the RAF request for increased wing incidence a major re-design of the central fuselage would have normally be undertaken, but because of time restraints, Short decided on a “quick fix” by lengthening the main landing gear legs to give a higher ground angle.

At the end of 1938, this change was incorporated on the Short S.31 prototype.

While testing with the S31/M4, construction began on two full size prototypes now officially known as the Stirling MkI/P1. Shortly after construction of the prototypes began, the Air Ministry decided to order the Stirling into production with a contract of 100 Stirling MkI’s as the second string for the Supermarine 316 and formally ordered in October. 1938. The prototype S29 was rolled out of the company’s Rochester factory on 13 May 1939.

Given the RAF serial number L7600, the prototype made its maiden flight on 14 May 1939 (with four Bristol Hercules II engines). After a graceful takeoff and short test flight it suffered an undercarriage failure on landing and was damaged beyond repair. The failure was traced to the light alloy undercarriage back arch braces which were replaced on succeeding aircraft by stronger tubular steel units.

The second prototype (L7605) was fitted with the strengthened undercarriage and made its maiden flight on 3 December 1939. For this flight the gear was left down, but happily for both Short and the RAF, the revised undercarriage held up when put to the tests of retraction, lowering and landing. During the spring of 1940, the prototype spent four months undergoing service tests at Boscombe Down.

Deliveries of production aircraft to the RAF began in August 1940. It was built initially by the parent firm at Rochester and by Short and Harland at Belfast, where the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA) opened No.8 Ferry Pool (FP) to clear them.

The first production version for the RAF was the Stirling I powered by four 1185kW Bristol Hercules XI radial engines and without a dorsal turret fitted. First in action in February 1941, the Stirling carried 7 tons of bombs for 590 miles, and was armed with eight machine guns. It went into service with 7 Squadron at Leeming in August 1940, and remained in production throughout the war. Prior to its first operational sortie, ATA is recorded as having ferried 12.

Both the factories were bombed in the summer of 1940, after which production was further distributed to the Austin Motors shadow factory at Longbridge, Birmingham, and to a new Shorts factory at South Marston, Swindon.

The Stirling II, only a few of which were completed, was a conversion of the Mk I with Wright R-2600-A5B Cyclone engines. The Mk III had four 1,230kW Bristol Hercules XVI engines and featured a mid-upper turret.

In order to train pilots on the new aircraft, each Stirling squadron formed its own conversion flight and in December 1941, a training unit was created at Thruxton with the specific purpose of training ATA pilots who would have to ferry them. This unit moved to Hullavington in May 1942, to Marharn in August and to Stradishall in October.

When by 1943 the output of heavy bombers had risen to over 400 a month, more ATA four-engined rated pilots were urgently needed to move them. When in February 1943 an ATA Halifax training unit, which had been opened at Pocklington stood down, to fill the gap in four-engined training, ATA reverted to a previous arrangement for its pilots to be given conversion courses with 1647 Stirling Conversion Unit at Stradishall.

From 1943, when the Stirling was no longer a suitable bomber, unlike the Mk III, the Stirling IV was produced from new as a long-range troop transport and glider tug (Horsa glider), the nose and upper turrets being removed and replaced by fairings, although the four-gun tail turret was retained. Up to 24 paratroops or 34 airborne troops could be carried. The final version of the Stirling was the Mk V, an unarmed military transport and freighter with a redesigned nose.

Total production of the Stirling – the Mk III of which was the major variant – was about 2,380.

On the night of 7-8 April 1945, RAF Stirlings of 38th Group dropped two battalions of French parachutists, including both regular soldiers and members of the French Resistance, into Holland south of Groningen. The aim was to support the advance of the Canadian Second Division.

Stirling I

Max speed: 260 mph

Range: 1930 miles

Crew: 7/8

Armament: 8 x .303 Browing mg

Bombload: 14,000 lb

Stirling Mk III

Engines: 4 x Bristol Hercules XVI, 1230kW / 1627 hp

Max take-off weight: 31751 kg / 69999 lb

Empty weight: 19595 kg / 43200 lb

Wingspan: 30.2 m / 99 ft 1 in

Length: 26.59 m / 87 ft 3 in

Height: 6.93 m / 23 ft 9 in

Wing area: 135.63 sq.m / 1459.91 sq ft

Max. speed: 235 kt / 435 km/h / 270 mph

Cruising Speed: 200mph (323kmh)

Service ceiling: 5180 m / 17000 ft

Max range: 1747 nm / 3235 km

Range w/max.payload: 950 km / 590 miles

Range: 2,010 miles (3,242km) with 3,500lb (1,589kg) bombload

Armament: 8 x .303in / 7.7mm machine-guns

Max. bomb load: 14,000 lb / 6,350 kg

Crew: 7-8

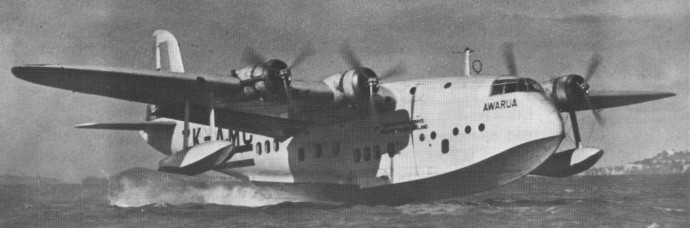

Following on from the Empire class flying boats, Short was keen to explore the limits of the flying-boat design, while also investing in the S.32 land airliner. A number of drag and stability improvements were proved and then embodied in the enlarged version of the Empire boat named the G class, or Golden Hind, and featuring improved power and range. The intention for this design (of which three were ordered by Imperial Airways) was to implement a regular scheduled service across the Atlantic in association with Pan Am.

World War II intervened and the three G boats were sequestered by the RAF and converted for ASW/reconnaissance use for which gun turrets and depth charge housings were installed. In 1942 they were reconverted to carry up to 40 passengers and used on services to Africa.

In late 1941 the two surviving G boats were returned to civil duties, but only one example survived the war. After a brief operational period the aircraft fell into disuse.

Engines: 4 x Bristol Hercules IV or XIV 14-cylinder radial, 1380 hp

Wingspan: 40.90 m / 134 ft 2 in

Length: 31.40 m / 103 ft 0 in

Height: 11.45 m / 38 ft 7 in

Wing area: 2159.904 sq.ft / 200.66 sq.m

Weight empty: 37712.1 lb / 17103.0 kg

Max take-off weight: 33800 kg / 74517 lb

Max. speed: 181 kts / 336 km/h / 209 mph

Cruising speed: 157 kts / 290 km/h

Service ceiling: 16896 ft / 5150 m

Cruising altitude: 7497 ft / 2285 m

Range: 2781 nm / 5120 km / 3182 miles

Crew: 5

Passengers: 40

Armament: 12x cal.303 MG (7,7mm), 907kg Bomb.

The Sunderland maritime-patrol and reconnaissance flying-boat was designed to meet the requirements of Air Ministry Specification R.2/33 and was virtually a military version of the Empire boat. The prototype flew for the first time on 18 October 1937, just over a year after the first Empire began its trials.

Entering service in June 1938, by the outbreak of war there were three squadrons of RAF Coastal Command operational with it and others in the process of re-equipping or forming. The Sunderland was notable for being the first flying-boat to be equipped with power-operated gun turrets.

The first production version was the Sunderland I powered by Bristol Pegasus 22 engines and armed with eight 7.7mm machine-guns: two in a Fraser-Nash nose turret, four in a Fraser-Nash tail turret, and two on hand-operated mountings in the upper part of the hull aft of the wing trailing edge.

The Sunderland II had Pegasus XVIII engines, but was otherwise similar to the Mk I, although late models were fitted with a two-gun dorsal turret in place of the manually operated guns.

The Mk III used the same power plant as the Mk II, but had a modified hull with a stream-lined front step and a dorsal turret as standard.

The final military version was the Sunderland V, the IV having become the Seaford. The Mk.5 was used mainly as a maritime reconnaissance flying boat they were powered the more powerful l200hp Pratt & Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasp. Wing span remained the same, however, the aircraft was slightly longer at 85’ 4”. Due to the increased power, the MAUW was 65,000lbs, but the maximum speed remained relatively unchanged. Armed with six Browning .303 machine-guns carried in two turrets (four in the rear and two in the forward), and four .303s fixed, that were controlled by the pilot. There were also two 0.5 Browning, which were manually operated, positioned in the beam hatches. Eight depth charges were carried on racks which were run out from the bomb room, along rails which extended under the wings. As with all the guns, these could be reloaded in flight.

Production continued until October 1945 and seven hundred and forty-nine Sunderlands were built, and they served throughout the war. The final Coastal Command Sunderland operational mission was in June 1945 over four weeks after the German surrender. Long-range Sunderland operations also took place overseas from bases in Africa and the Far East.

In 1943 a number of Sunderlands were de-militarised, equipped to carry 20 passengers and turned over to BOAC. The Short S.25 Sandringham was produced during the Second World War by the demilitarized conversions of Short Sunderland military flying boats previously operated by the Royal Air Force.

Post-war the type took part in the Berlin Airlift carrying 4920 tonnes (4847 tons) of freight. During the Korean War Sunderlands based in Japan undertook nearly 900 operational sorties totally over 13350 hours of flying. The Sunderland finally retired from RAF service in 1959 when the last aircraft were scrapped at RAF Seletar, Singapore.

Sandringham

Engines: 4 x Bristol Pegasus XVIII

Cruise: 200 mph

Pax capacity: 16-24

Sunderland Mk. III

Engines: 4 x 1065hp Bristol Pegasus radials

Wing span: 112 ft 10 in

Length: 84 ft 4in

MAUW: 58, 000 lb

Top speed: 210mph at 7,000ft

Sunderland Mk V

Engines: 4 x Pratt-Whitney R-1830-90B Twin Wasp, 895kW / 1200 hp

Max take-off weight: 29480 kg / 64993 lb

Empty weight: 16740 kg / 36906 lb

Wingspan: 34.38 m / 113 ft 10 in

Length: 26 m / 85 ft 4 in

Height: 10.52 m / 35 ft 6 in

Wing area: 156.72 sq.m / 1686.92 sq ft

Max. speed: 185 kt / 343 km/h / 213 mph

Cruising speed: 116 kt / 214 km/h

Service Ceiling: 5455 m / 17900 ft

Range: 2337 nm / 4300 km / 2672 miles

Armament: 2 x .5in / 12.7mm Browning machine-guns, 10 x .303in / 7.7mm machine-guns

Bombload: 2250kg / 8 x depth charges

Crew: 13

In 1935 the British government took the bold decision to carry all mail within the Empire at the ordinary surface rate. Combined with increasing passenger traffic, this called for a sudden expansion of Imperial Airways and the equally bold decision was taken to buy 28 of a totally new flying-boat, known as the C Class Empire, ‘off the drawing board’ from Short Brothers, at a cost of over £2,000,000. They were four engined cantilever monoplane with a hull of advanced lines.

Features included light-alloy stressed-skin construction; a cantilever high wing with electric Gouge flaps; four 685kW Bristol Pegasus Xc radial engines driving DH Hamilton two-position propellers; and a streamlined nose incorporating an enclosed flight deck for captain, first officer, navigator and flight clerk. A steward’s pantry was amidships and in the normal configuration seats were arranged in front and rear cabins for 24 passengers. On long hauls sleeping accommodation was provided for 16, with a promenade lounge. On some routes experience showed that the mail capacity had to be raised from 1.5 to 2 tonnes, reducing the passenger seats to 17.

The prototype, the Short S.23 named Canopus, flew on July 4, 1936. Less than four months later, on October 30, it was in passenger service. Others followed at fortnightly intervals and by 1937 the fleet was already covering 113,196 miles per week on scheduled services.

The original C Class boats had four 910 hp Bristol Pegasus engines and could carry 17 pass¬engers, plus two tons of mail and freight for 810 miles at 164 mph. They were soon followed by seven more with 900 hp Perseus engines and double the range of the first batch.

All 28 were delivered, plus three for Qantas (Australia). Two were long-range boats with increased weight and transatlantic range. Eleven S.30s (eight for Imperial and three for Tasman Empire Airways) had 663kW Perseus XIIc sleeve-valve engines and greater range – the first four also being equipped for flight refuelling to greater weight. The final two boats were S.33s with increased weight and Pegasus engines.

On 5 August 1935, Imperial Airways began regular trans-Atlantic airmail flights using Short Empire flying boats which were refuelled in the air.

During World War II most of these great aircraft served on long routes all over the world. Four were impressed for RAF use with radar (two being destroyed in Norway in May 1940) and most were re-engined with the same 752kW Pegasus 22 engines as the Sunderlands (the derived military version). Their achievements were amazing: one made 442 crossings of the Tasman Sea, two evacuated 469 troops from Crete and one was flown out of a small river in the Belgian Congo in 1940. Others maintained schedules on the North Atlantic, between Britain and Africa, the dangerous Mediterranean route from Gibraltar to Malta and Cairo, and the Horseshoe route between Australia, India and South Africa. Most were retired in 1947.

The prototype completed 2,024,745 miles of safe flying in her ten years of service.

S.23 C-Class

Engines: 4 x Bristol Pegasus XC, 790 hp / 686kW

Wing span: 114 ft 0 in (34.75 m)

Length: 88 ft 0 in (26.82 m)

Height: 31 ft 9.75 in (9.68 m)

Wing area: 139.35 sq.m / 1499.95 sq ft

Empty weight: 10659 kg / 23499 lb

Max TO wt: 40,500 lb (18,375 kg)

Max level speed: 200 mph (322 kph)

Cruise speed: 265 km/h / 165 mph

Ceiling: 6095 m / 20000 ft

Range: 1223 km / 760 miles

Crew: 5

Passengers: 17-24

S.30

Engines: 4 x 910 h.p. Bristol Pegasus

Length: 88 ft. (26.82 m.)

Wing span: 114 ft (34.74 m.)

Weight empty: 23,500 lb. (10,660 kg.)

Max speed: 200 mph

Max cruise: 165 mph (265 kph)

Ceiling: 20,000 ft. (6,000 m.) fully loaded

Range: 800 miles (1,300 km.)

Crew: 5

Pax cap: 24

1935

S.22

Engines: 4 x 90hp Pobjoy Niagara III

Wingspan: 16.76 m / 55 ft 0 in

Length: 12.80 m / 42 ft 0 in

Wing area: 37.16 sq.m / 399.99 sq ft

Max take-off weight: 2608 kg / 5750 lb

Empty weight: 1504 kg / 3316 lb

Max. speed: 225 km/h / 140 mph

Cruise speed: 195 km/h / 121 mph

Ceiling: 3658 m / 12000 ft

Range: 676 km / 420 miles

Crew: 1-2

Passengers: 10

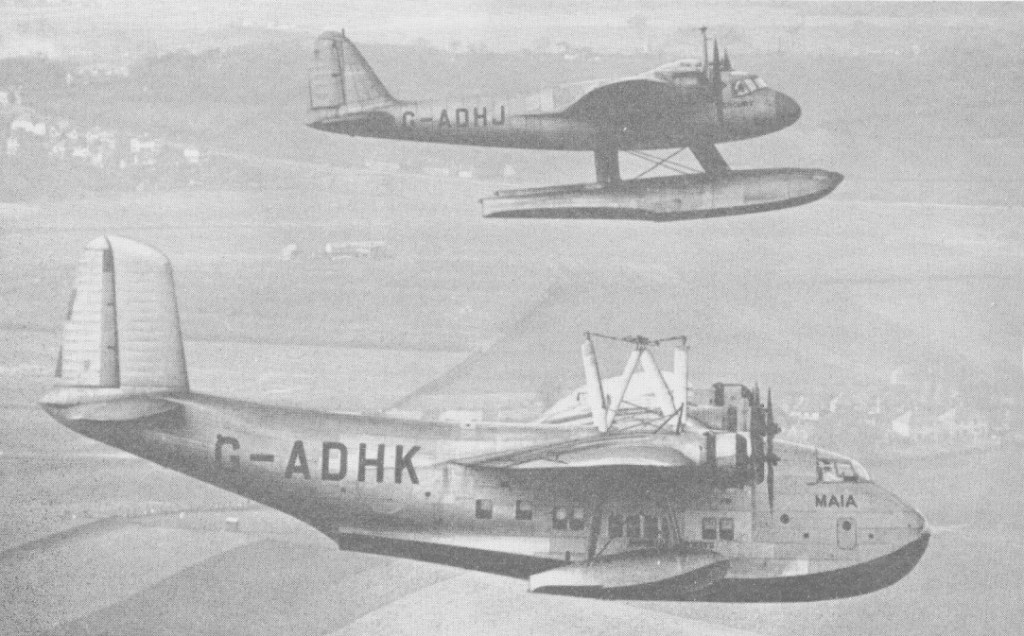

Tests had proved that an Imperial Airways’ Empire flying-boat could achieve a transatlantic crossing only if its entire payload consisted of fuel. Since it is well known that an aircraft can be flown at a much greater weight than that at which it can take off from the ground, Robert Mayo proposed that a small heavily loaded mailplane be carried to operational altitude above a larger ‘mother plane’ and then released to complete its long-range task. The proposal was accepted by the Air Ministry and Imperial Airways, which jointly contracted Shorts to design and build such a composite unit.

The Short S.21 Maia, the lower component, was a slightly enlarged and modified version of the Empire boat; the Short S.20 Mercury, the upper long-range unit, was a new high-wing twin-float seaplane with four 254kW Napier Rapier H engines giving a cruising range of 6116km with 454kg of mail.

This eight engined part time biplane composite was first tested on 4 January 1938. During take off and before separation Mercury’s flying controls were automatically locked in the neutral position, Maia’s pilot having full command; the parasite’s engines were started from inside the mother ship and combined with those of Maia to get the two components airborne.

The first airborne separation took place on 6 February 1938, over Rochester, Kent, and after a number of experimental flights Mercury was air-launched over Foynes Harbour, County Limerick, Ireland crewed by Captain Donald Bennett, on 21 July 1938. Mercury carried 5455 litres (1200 Imperial gallons) of fuel in its wings and 508 kg (1120 lb) of newspapers, mail and newsreel footage in her twin floats. Bennett flew on to Montreal nonstop, covering the 4715 km (2930 miles) from Ireland in 13 hours 29 minutes, then set off again for New York, where for the first time ever English newspapers were on sale at the news stands on the day after publication.

From 6 October 1938 Mercury and Bennett made news again with a nonstop flight of 9728 km (6045 miles) from Dundee, Scotland to Orange River, South Africa in 42 hours 5 minutes.

The Composite subsequently operated a scheduled nonstop mail service between Southampton and Alexandria, Egypt which continued until the outbreak of World War II.

Mercury was eventually broken up at Rochester and Maia destroyed by enemy action during May 1941.

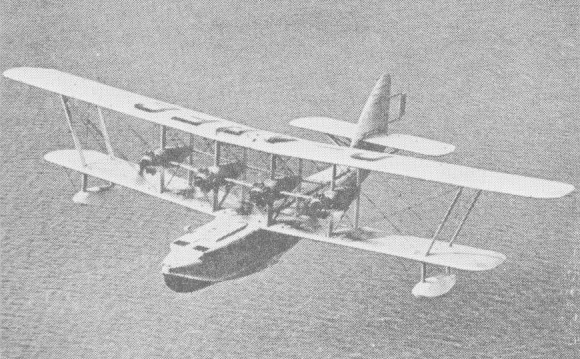

The closure of Italian and Italian colonial seaports to Imperial Airways in the Mediterranean in 1929 brought a need for a longer range flying boat, with mail carriage a priority. The Kent biplane flying boat was Short’s response, and three were built.

During the spring of 1933, Imperial Airways asked Short Brothers to develop a landplane version of its Kent flying boat. Differing little from the Kent, apart from the wheeled undercarriage and principally different in having a rectangular fuselage and a fixed undercarriage., Scylla and Syrinx were constructed outdoors since Shorts had no means of building and flying a landplane at its own facilities and was forced to use Rochester airport due to the urgency of the requirement.

Both of the new aircraft entered scheduled service on 7 June 1934, on the Paris route. The cabins featured three passenger compartments, two toilets and a buffet. The average cabin width was almost 11 ft / 3.35 m.

Scylla did suffer a minor accident at Paris Le Bourget on 3 August 1934.

The two Scylla examples stayed in service longer, and had very short RAF careers in 1939-40. They were the last of Short’s biplane designs and the last in service.

The closure of Italian and Italian colonial seaports to Imperial Airways in the Mediterranean in 1929 brought a need for a longer range flying boat, with mail carriage a priority. The Kent biplane flying boat was Short’s response, and three were built. Imperial Airways also persuaded Short to produce a landplane version of the L.12 Kent – the Scylla.

Short L.12 Kent

Engines: 4 x 555hp Bristol Jupiter XFBM nine-cylinder radial

Max take-off weight: 14515 kg / 32000 lb

Wingspan: 34.44 m / 113 ft 0 in

Length: 23.90 m / 78 ft 5 in

Height: 8.53 m / 28 ft 0 in

Max. speed: 220 km/h / 137 mph

Ceiling: 5335 m / 17500 ft

Range: 724 km / 450 miles

Crew: 2

Passengers: 16