A tri-motor low-wing mailplane built in 1934.

Ogden’s only product was the trimotor Osprey cabin monoplane, offered in three versions: the Model C, which carried two crew and four passengers (seven passengers if the toilet was removed), the Model PB with Menasco B4 engines, and the Model PC with Menasco Pirate engines.

Only six were built, limited by the crisis of 1929.

Northrop’s postwar model was intended for the less developed parts of the world where airline operations frequently involved short, unprepared runways. The Pioneer was a 36-passenger (or a combination of fewer passengers but more cargo) design with three 800hp (600kW) Wright R-957 C7BA Cyclone engines and a fixed, conventional landing gear. The prototype made its first flight from Hawthorne, California, on December 21, 1946.

Full-span flaps and retractable ailerons, which had been successfully tested on the P-61 Black Widow, enabled the Pioneer to takeoff at its maximum weight of 25,000lb (11,340kg) in less than 400ft (120m) and to land in 600ft (180m). Dual main landing gear wheels could be installed for operation from soft fields. The cruising speed was only 150mph (240km/h), but that was considered sufficient for the short stages on which the Pioneer would operate. After about a year of test flying, the Pioneer was lost when a make-shift dorsal fin failed during yaw tests. By that time, the Pioneer could not compete with the inexpensive military-surplus transports, even with its outstanding short-field performance. Although the Pioneer program was terminated, the basic design evolved into the larger Northrop C-125 Raider for the USAF. 23 were built with 894kW Wright R-1820-99 engines: 13 as C-125A assault transports and ten as C-125B Arctic rescue aircraft.

N-23 Pioneer

Engines: three 800hp (600kW) Wright R-957 C7BA Cyclone

Maximum take-off weight: 25,000lb (11,340kg)

TO dist: 400ft (120m)

Landing dist: 600ft (180m)

Cruising speed: 150mph (240km/h)

Capacity: 36-passenger

C-125A Raider

Engines: 3 x 894kW Wright R-1820-99 engines

C-125B Raider

Engines: 3 x 894kW Wright R-1820-99 engines

The first heavy attack type to see service from aircraft-carriers of the US Navy, the North American AJ Savage was developed (as the North American NA-146) using two Pratt & Whitney radial engines, augmented by a tail-mounted Allison J33 turbojet. In practice the type saw only limited use in the strategic bombing role for which it had been designed, being replaced from the mid 1950s onwards by the Douglas A3D Skywarrior, but several were subsequently modified to serve as inflight-refuelling tankers with a hose-and-reel unit in place of the turbojet.

In order to meet the specification’s demands a large aircraft was required, this in turn dictating the need far an unusual composite powerplants configuration – a pair of Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp radials as the primary engines augmented by an auxiliary Allison J33 turbojet in the lower rear fuselage.

This third engine was intended to provide a high speed ‘dash’ capability during the attack phase of the aircraft’s operation and for extra boost on takeoff when required. Other features included shoulder mounted folding wings, tricycle undercarriage, wing tip fuel tanks and (on the first models) dihedral tail planes.

An initial contract for three prototype XAJ-l (NA-146) aircraft was awarded to North American in late June 1946, and construction of these got under way almost immediately although more than two years were to elapse before the Savage took to the air for the first time on 3 July 1948. In its original guise the Savage was manned by a crew of three and was intended to carry a 4536-kg (10,000-lb) weapon load in an internal bomb bay in the aircraft’s belly. The three prototypes (121460 to 121462), were fitted with a flat horizontal tail.

These were followed by 55 initial production AJ-1s (NA-156, -160, and -169, 122590 to 122601, 124157 to 124186, and 124850 to 124864), the first one flying on 10 May 1949. The horizontal tail with dihedral. Production-configured aircraft began to enter service with Composite Squadron VC-5 in mid-September 1949, but it was not until the end of August 1950 that this unit was considered operationally ready, this marking the climax of several months of sea-borne trials aboard the USS Coral Sea. The AJ-1 was re-designated A-2A in 1962. The first carrier landings were performed aboard USS Constellation in August 1950. The first variant to see service with the US Navy was the AJ-l, of which 40 were built, and these were followed by 55 examples of the AJ-2 (NA-163and NA-184, 130405 to 130421, and 134035 to 134072) which featured slightly more powerful radial engines as well as increased fuel capacity, a slightly longer fuselage and a taller fin and rudder to improve handling qualities. The AJ-2 first flew on 19 February 1953 and was re-designated A-2B in 1962.

This photo is AJ-2 130418, probably taken in 1971, possibly at Bridgeport CT. It is wearing markings applied by Avco Lycoming while used an engine test-bed, registered N68667. Following its naval use, it was used as a fire bomber in Oregon, registered N101Z, before going to new owners. In 1984 it was flown to the Naval Air Museum at Pensacola and is now on display in USN markings.

Preceding the AJ-2 bomber was the photo-reconnaissance AJ-2P (NA-175 and NA -183, first flight 30 March 1952) equipped with 18 cameras for day and night photography at high and low altitudes, photo-flash bombs in the weapons bay, automatic control of most of the cameras, the associated electronics equipment in a modified nose and additional fuel capacity. Four US Navy combat squadrons were still operating the AJ-2 in 1958 and these received AJ-2Ps.

A total of 30 AJ-2Ps was built, 128043 to 128051, 129185 to 129195, 130422 to 130425, and 134073 to 134075, this being the last model to see squadron service, not being retired from the active inventory until the beginning of 1960. The AJ-2P has distinctive radar “thimble” nose and zero-dihedral stabilizer.

A number of AJ-1s and AJ-2s were converted to flight refuelling tankers with a hose-and-reel unit installed in the weapons bay. The few Savages still in service in September 1962 when all USAF and USN aircraft designations were combined into the existing Air Force system were redesignated A-2A (AJ-1) and A-2B (AJ-2).

AJ Air Tankers of Van Nuys CA converted two as fire fighters after removing the J-33 in the tail, showing one in action with no big prop spinners and a firefighting scheme with a big #88 about 1988.

In 1948 North American began work on the NA-163 turboprop-powered derivative of the AJ-1 Savage, two prototypes being ordered in September of that year. The US Navy specified major changes, including deletion of the Allison J33 booster engine, and the first prototype North American XA2J-1, 124439, did not fly until 4 January 1952. Development was hampered by problems with the Allison XT40-A-6 engines, each of which comprised two T38 engines driving contra-rotating propellers through a gearbox, allowing either T38 in each unit to be shut down for long-range cruise. The three-man crew was provided with a pressurised cabin and defensive armament comprised two 20mm guns in a remotely-controlled barbette. Maximum offensive load was 4911kg of bombs. The completed second prototype, 124440, was never flown. One ended up being burned in a fire-fighting demo at Edwards AFB in 1962.

AJ-2 Savage

Engines: 2 x 2,500-hp (1864-kW) Pratt & Whitney R-2800-48 radial and 1 x 4,600-lb (2087-kg) thrust Allison J33-A-10 turbojet

Max speed: 628 km/h (390 mph)

Service ceiling: 12190 m(40,000 ft)

Range 3540 km (2,200 miles)

Empty wt: 12247 kg (27,000 lb)

Maximum take-off wt: 23396 kg (51,580 lb)

Wing span 21.77 m (71 ft 5 in)

Length 19.23 m (63 ft 1 in)

Height 6.22 m (20 ft 5 in)

Wing area 77.62 sq.m (835.5 sq ft)

Armament: up to 4536 kg (10,000 lb) of bombs carried internally.

Crew: 3

AJ-2

Engines: 2 x Pratt & Whitney R-2800-44W, 1790kW + Allison J33-A-19 auxiliary turboprop, 2087kg

Max take-off weight: 23973 kg / 52852 lb

Wingspan: 22.91 m / 75 ft 2 in

Length: 19.20 m / 62 ft 12 in

Max. speed: 758 km/h / 471 mph

Crew: 3

AJ-2P Savage

Carrier-based photo-reconnaissance and attack bomber

Engines: 2×2,400 h.p. Pratt & Whitney R2800-48W and 1 x 4,600 lb. thrust Allison J33-A-10

turbojet.

Wingspan: 71 ft. 5 in

Length: 65 ft.

Loaded weight: 55,000 lb.

Max. speed: 425 m.p.h.

Ceiling: 40,000 ft.

Typical range: More than 3,000 miles at 290 mph

Payload: 12,000 lbs internal

Operational equipment: 18 cameras

Armament: 2 x 20mm cannon

Crew: 3

XA2J-1

Engines: 2 x Allison XT40-A-6 turboprops

Armament: 2 x 20mm cannons, 4900kg of weapons

Crew: 3

The Russian “Dirizhablestroem” was staged with developing the production of semi-rigid airship types. In order to speed up the execution of the tasks, in 1932 in the Soviet Union invited Italian Umberto Nobile, who was to head the technical management of the project.

In 1931 Umberto Nobile left Italy to work for the next four years in the Soviet Union where he helped with the Soviet semi-rigid airship programme. There is an obvious Nobile influence in the design of the airships USSR-V5, and SSSR-V6 OSOAVIAKhIM.

By the end of February 1933 USSR-V5 was prepared as the first semi-rigid airship in the. On April 27, 1933 Nobile first took to the air. This airship was of small size, its volume was only 2,340 cubic meters. It was explained that the USSR B-5 was conceived as a semi-rigid airship, established to give Russian designers practical experience with Italian semi-rigid systems, and identifying those problems that might face in the USSR in the production of airships larger volume. In addition to the B-5 was planned to conduct training of ground staff and pilots.

In May 1933, after passing a series of municipal acceptance tests, B-5, was admitted to the civilian air fleet. In 1933, Nobile made over a hundred flights. The experience gained during its construction, and operation was the basis for the construction of the largest airship in the USSR-6 “Osoaviakhim.”

The CCCP B-5 (USSR V5) was dismantled in 1934 – her ‘envelope’ was leaking and generally unreliable. While a new ‘envelope’ development has been in progress, lightning struck the hangar near Moscow where parts of the dirigible were stored. Everything went down to ashes, not only cases with B-5 parts, but her sistership B-4 (also dismantled) and a brand-new B-7 as well.

Engines: 3 × Piston engines, 140 kW (190 hp) each

Volume: 19,400 cu.m (685,000 cu.ft)

Length: 104.5 m (344 ft 6 in)

Diameter: 18.8 m (65 ft 7 in)

Gross weight: 12,000 kg (26,400 lb)

Useful lift: 9,300 kg (20,460 lb)

Maximum speed: 93 km/h (58 mph)

Range: 2000 mi

Range 1937: 3107 mi

Endurance: 130 hr 30 min

Crew: 15

Airship Italia was a semi-rigid airship by Italian engineer Umberto Nobile and used in his second series of flights around the North Pole. Italia was an N-class semi-rigid airship, designation N-4. In design it was almost identical to the N-1 Norge but slightly larger in gas capacity. According to Italian sources, airship N-5 (which was larger and had three times the lifting capacity of N-1) was Nobile’s preferred design for the Arctic expedition, but when funding was refused by the Italian government he built N-4 with the assistance of private backers and the City of Milan.

First flown in 1924, in May 1928 the Italia set off for the Arctic Circle, stopping at a German airship hangar at Stolp, Pomerania, and the airship mast at Vadsø in Norway.

It crashed in 1928, with one confirmed fatality from the crash, one fatality from exposure while awaiting rescue, and the disappearance (and presumed death) of six crew members who were trapped in the still-airborne envelope.

At 01:15 on 15 April 1928, the Italia took off from its base at Milan for the Arctic. With 20 personnel on board, and a payload of 17,000 pounds of fuel and supplies, the journey to Stolp in Germany took 30 hours through a variety of bad weather conditions. Near Trieste a wind gust damaged one of the tail fins. Later in the Sudetes the ship faced severe hailstorms and narrowly escaped lightning strikes.

On arrival at Stolp at 07:15 on 16 April 1928, inspection revealed hail damage to the propellers and envelope, and severe tail fin damage. All the ballast and most of the fuel had been used fighting the wind. Repairs took 10 days, and required parts and technicians to be sent from Italy.

Takeoff from Stolp was further delayed by bad weather, but at 03:28 on 3 May 1928, Italia set off for Norway. Eight hours later, escorted by Swedish naval planes, Italia passed over Stockholm. Crewmember Finn Malmgren spotted his house from the air and the ship descended to drop a letter to his mother. Bad weather forced the ship east over Finland, and they passed over Rovaniemi at 01:49 on 4 May. Italia reached the mooring mast at Vadsø later that day.

While the ship was moored without difficulty, blizzard conditions followed by heavy rain kept the crew in a state of constant anxiety and caused minor structural damage. As soon as weather permitted, Italia took off for Kings Bay at 20:34 on 5 May, and by 05:30 had passed the meteorological station on Bear Island, but ran into high winds shortly after, also suffering an engine failure. By 12:00 on 6 May the airship reached Ny-Ålesund (Kings Bay) and spotted their support ship. However, in a foretaste of events to come, Captain Romagna of the Città di Milano refused to release 50 men requested by Nobile to form a landing crew. The Norwegian authorities summoned 150 miners at short notice to help haul the ship down and walk her to the shed.

Nobile planned 5 flights for the expedition, each starting from and returning to Ny-Ålesund (Kings Bay) and exploring different areas of the Arctic.

After the necessary engine and structural repairs were completed, the first flight departed from Kings Bay on 11 May 1928. Italia was forced to turn back after only eight hours flight because of thick ice forming on the envelope, as well as fraying of the control cables due to the extreme conditions.

The second flight left at 13:20 on 15 May and lasted 60 hours. In contrast, this time the weather conditions were excellent and visibility perfect. Valuable meteorological, magnetic and geographic data were gathered in a 2,500 mile (4,000 km) flight to the hitherto uncharted Nicholas II Land and back. Malmgren gathered weather and ice observations, while Pontremoli and Běhounek made measurements of magnetic phenomena and radioactivity. The ship returned safely to base on the morning of 18 May.

The third flight started on 23 May 1928, and following a route along the Greenland coast, with the assistance of strong tailwinds, reached the North Pole 19 hours later at 00:24 on 24 May 1928. Nobile had prepared a winch, an inflatable raft, and survival packs (providentially as it turned out) with the intention of lowering some of the scientists onto the ice, but the wind made this impossible. Instead they circled the pole making observations and at 01:20 dropped the Italian and Milanese colours, as well as a wooden cross presented by the Pope and a religious medal from the citizens of Forlì onto the ice during a short ceremony. At 02:20 on 24 May, the Italia started back to base.

The same tail wind that had helped Italia to the Pole now impeded their progress. Nobile calculated the return journey would take 40 hours, and had discussed their options with Dr Malmgren in the hours before their arrival at the Pole. Nobile considered a trans-polar route to Mackenzie Bay in Canada. According to Nobile, Malmgren advised a return to Kings Bay, predicting lessening winds on their return trip. On the other hand, Malmgren predicted a head wind all the way if the Canadian route was attempted.

Heading directly south on a heading for Kings Bay, after 24 hours of increasing head winds and thick mist the Italia was only halfway back to base. The airship struggled to gain ground and break through to the zone of calmer winds which expedition meteorologist Finn Malmgren predicted was just ahead. Ice formed on the propellers and shot off into the envelope, necessitating running repairs. Engine speed was increased but with little effect, except for a doubling of fuel consumption. Dr Běhounek, in charge of the compass, started reporting variations in course of up to 30 degrees, and the elevator man Cecioni had similar problems maintaining control. By 07:30 on 25 May, Nobile, who had been awake for over 48 hours, knew that the situation was critical and Giuseppe Biagi, the wireless operator, sent out the message: “If I don’t answer, I have good reason”. By dead reckoning, Nobile estimated his position as 250 miles (400 km) northeast from Moffen Island. This estimate was 350 miles (560 km) off.

At 9:25am on 25 May the first critical incident occurred, when the elevator control jammed in the downward position while the ship was travelling at less than 1000 feet (300 metres) altitude. All engines were stopped and the airship began to rise again after it had dropped to within 300 feet (90 metres) of the jagged ice pack. The airship was allowed to continue rising to 3000 feet (900 metres) and above the cloud layer into bright sunlight for 30 minutes. After two engines were restarted the ship descended to 1000 feet (300 metres) with no apparent ill effect, with the headwind appearing to decrease slightly allowing an airspeed of 30 mph. Malmgren took the helm with Zappi supervising him. Cecioni continued to operate the elevators.

At 10:25 the ship was noticed to be tail-heavy and falling at a rate of 2 feet per second (0.6 m/s). Nobile ordered full elevators and emergency power, but although the nose rose to an upward angle of 21 degrees, the descent continued. Nobile ordered foreman rigger Renato Alessandrini to the tail of the envelope to check the automatic gas valves. A short time later, seeing a crash was unavoidable, Nobile ordered full stop and the cutting of electrical power to prevent a fire on impact. The port engine engineer failed to notice the order and the ship began to bank. At the same time Nobile ordered Cecioni to dump the ballast chain, but was unable to carry out the order in time owing to the steep angle of the floor and the secure way the chain was lashed.

Seconds afterwards the airship’s control cabin hit the jagged ice and smashed open. Suddenly relieved of the weight of the gondola, the envelope of the ship, with a gaping tear in the keel and part of one cabin wall still attached, began to rise again.

Cecioni was hurled out the ruptured cabin and into a mound of ice injuring both his legs. As he looked up he saw the envelope drifting above him, and Ciocca halfway out of the starboard engine car staring down in horror. Lago, Dr Pontremoli, and Alessandrini were also visible, in the torn opening where the companion way had been. Chief Engineer Ettore Arduino, with remarkable presence of mind, started throwing anything he could lay his hands on down to the men on the ice as he drifted slowly away with the envelope. These supplies, and the packs intended for the descent to the ice helped keep the survivors alive for their long ordeal on the ice. Arduino perished with the drifting airship envelope.

Troiani, at the engine control signals fared better, being hurled into soft snow and rolling before immediately jumping to his feet and cleaning the snow off his glasses, which had survived the crash unscathed. Viglieri and Mariano, standing next to the chart table, briefly saw the rear engine car about to strike the ice hard and then found themselves prostrate but unharmed in a mass of debris. Biagi, with no time to send out an SOS grabbed the portable emergency radio and wrapped his arms around it trying to save it from damage. The impact on the ice winded him but left him inside the wreck of the cabin. Nobile lay unconscious with a head wound, with Malmgren and Zappi nearby.

Nine survivors and one fatality were left on the ice, and six more crew were trapped in the still drifting airship envelope. The envelope and the crew members aboard it have never been found. The position of the crash was close to 81°14′N 28°14′E, about 120 km (75 mi) northeast of Nordaustlandet, Svalbard. The drifting sea ice later took the survivors towards Foyn and Broch islands.

Mariano, Běhounek, Trojani, and Viglieri were on their feet first and began to examine the others for injuries. Nobile gradually regained consciousness – he had a broken leg, right arm, and cracked rib in addition to the wound on his head. Cecioni had two badly broken legs. Malmgren had an injured shoulder (possibly broken or dislocated), and much later was suspected to have internal injuries to his kidney. Zappi had severe chest pains from suspected broken ribs.

Almost immediately the survivors were buoyed by the discovery of a waterproof bag containing chocolate, pemmican, a Colt revolver, ammunition and a flaregun. Biagi’s radio was intact and he began searching for material to construct a radio mast. Biagi soon discovered the rear engine car smashed on the ice, and the body of Pomella, who had apparently survived the impact and sat down on a block of ice, but died minutes afterwards from a head injury. Despite this shock Biagi erected an antenna and within a few hours began to send the first SOS from the stricken survivors. Nobile and Cecioni were placed together in a sleeping bag for warmth and spent the next few hours in semi-consciousness while the others gathered what they could from the wreck. According to Nobile, Malmgren, in pain, and suffering from guilt about his role in the crash announced he would drown himself and began walking away from the crash site, only stopping when sharply ordered to return by the General. Later the same day, Mariano had to disarm Malmgren after he started to walk away from the crash site with the loaded Colt revolver. Meanwhile, the uninjured men surveyed the ice pack, collecting supplies and chose a stable patch of ice to erect a 2.4 x 2.4 metre (8 ft x 8 ft) silk tent they recovered which was to be their only shelter during the coming ordeal.

The day after the crash was spent looking for more supplies amongst the wreckage. Navigational instruments and charts were recovered allowing the position of the crash site to be calculated. The quantity of rations per man was also calculated. This was a scant 300 grams (11 oz) of food per day, mainly pemmican and chocolate, calculated for a 25-day stay on the ice. Eventually 129 kg (284 pounds) of food were recovered extending this supply to 45 days. Finally the crowded tent was dyed red for improved visibility from the air, with dye marker bombs that had been aboard the airship. Biagi continued to signal for help with his radio; the survivors quickly became exasperated at the stream of mundane personal messages pouring out of the Citta di Milano interspersed with occasional messages for the Italia. After several days cold began to take its toll. The fliers had been equipped with many layers of woollen clothes and lambskin flight suits, but not all of them were fully dressed at the time of the crash and none had proper Arctic survival clothing. On 28 May land was sighted in the distance, breaking the despondency of the survivors. Discussions began as to whether the survivors should attempt a trek towards land and eventually it was decided that Malmgren, Zappi and Mariano should be sent to try to summon help. On 29 May Malmgren shot a polar bear which approached the crash site, augmenting the food supply with about 189 kg (400 pounds) of fresh meat.

An international rescue effort followed, but was bedevilled by official apathy and political interference on the part of the Italians. Romagna, the commander of the base ship, seemed to be paralysed with indecision when the Italia went missing. Lengthy telegrams asking for instructions were sent to Rome, but there was no effort to move the ship closer to the presumed crash site or otherwise begin a search. The Citta di Milano was admittedly old and unsuited to the Arctic, but considering the season could easily have taken up station further north and west of Kings Bay without any danger to itself. No attempt was made to keep a radio watch, and Guglielmo Marconi, who monitored the messages from the base ship later said:

“No wonder that on the Citta di Milano the SOS of the survivors could not be picked up by radio operators. They simply were not paying attention to her signals.”

Pedretti, the alternate radio operator left behind by the Italia; and Amedeo Nobile, Umberto’s brother were the most concerned about the radio silence from the airship. Amedeo Nobile was the first to visit the Norwegian ship Hobby to try to get Norwegian help for a search. Word also reached Amundsen in Oslo, who immediately volunteered to start on a search mission. When the Norwegian government officially approached the Italian government proposing Amundsen as expedition leader, they were rebuffed and Lieutenant Hjalmar Riiser-Larsen was appointed instead. Almost every Arctic explorer of note offered assistance or money for the search, including the American Lincoln Ellsworth.

In Italy, Arturo Mercanti, former air force chief and friend of Nobile requested that air force planes be sent to the Arctic to begin a search. Repeatedly frustrated by official inaction he attempted to hire private aircraft himself and threatened to publicise the government’s inaction in the international press. As a result, two sea planes were sent from Italy, a Dornier Wal piloted by Luigi Penzo and a state-of-the-art Savoia-Marchetti S.55 piloted by Ten. Col. Umberto Maddalena who was the first rescuer to spot the “Red Tent” survivors on 20 June. Mercanti himself went to Kings Bay where his frustration continued.

Cpt. Gennaro Sora (of the Italian Army Alpini ski detachment) did run a heroic over-ice sled attempt from the Città di Milano support ship, while Matteoda and Albertini of the SUCAI (the University Section of the Italian Alpine Club) did the same from the Italian-hired ship Braganza. Both attempts were made in the face of opposition (some sources state direct orders) from the base-ship commander, Romagna.

The lack of co-ordination meant that it took more than 49 days before all the crash survivors (and stranded would-be rescuers) were retrieved. Roald Amundsen was lost, presumed dead, flying to Spitsbergen in a French Latham sea plane piloted by René Guilbaud to take part in the operation. Two hundred thousand cheering Italians met Nobile and his crew on arrival in Rome on 31 July. This show of popularity was unexpected by Nobile’s detractors, who had allegedly been seeding the foreign and domestic press with sensational accusations against him.

Crew and expedition members:

Umberto Nobile – Expedition leader. Survived.

Finn Malmgren – Swedish meteorologist and physicist. Died trekking for help.

František Běhounek – Czechoslovak physicist. Survived.

Aldo Pontremoli – Italian physicist (University of Milan). Lost with envelope, never found.

Ugo Lago – Journalist, Il Popolo d’Italia. Lost with envelope, never found.

Francesco Tomaselli – Journalist (Royal Italian Army Alpini). Not on final flight.

Adalberto Mariano – Navigator (Royal Italian Navy). Survived.

Filippo Zappi – Navigator (Royal Italian Navy). Survived.

Alfredo Viglieri – Navigator/hydrographer (Royal Italian Navy). Survived. Natale Cecioni – Elevator operator / Chief technician. Survived.

Giuseppe Biagi – Radio operator. Survived.

Ettore Pedretti – Radio operator. Not on final flight.

Felice Trojani – Elevator operator/Aeronautical project engineer. Survived.

Ettore Arduino – Chief engine mechanic. Lost with envelope, never found.

Calisto Ciocca – Starboard engine mechanic. Lost with envelope, never found.

Attilio Caratti – Port engine mechanic. Lost with envelope, never found.

Vincenzo Pomella – Rear engine mechanic. Killed in the crash.

Renato Alessandrini – Foreman Rigger. Lost with envelope, never found.

Titina – Fox terrier belonging to Gen. Nobile, expedition mascot. Survived

Chronology of the rescue operations:

25 May 1928 – The Italia crashes on the ice. Radio operator Biagi salvages radio, constructs a radio mast and begins transmitting SOS.

31 May – Survivors unable to establish radio contact because of weather conditions and negligence by base ship Città di Milano who fail to maintain radio watch and instead continue to send routine traffic. Malmgren, with Commanders Mariano and Zappi, begin a trek toward land.

3 June – A Soviet amateur radio operator Nikolai Schmidt in Vokhma village hears the Italia SOS signals.

5 June – A Norwegian pilot makes the first flight in search of the Italia. In the ensuing weeks, pilots from Norway, Sweden, Finland, Russia and Italy make search and rescue flights.

8 June – Radio contact established between the ice floe and the Città di Milano. Search operations continue.

June 15/16 – Malmgren collapses from exposure on the ice and asks to be left behind. His body is never found.

18 June – Roald Amundsen and five others disappear on a flight to Spitsbergen to aid in rescue operations. Captain Sora of the Italian Alpine troops defies orders and sets off by sled with Arctic explorers Ludvig Varming and Sjef van Dongen to try to reach the crash zone.

20 June – Italian pilot Maddalena spots the survivors and drops supplies, many of which are smashed or useless.

22 June – Italian and Swedish pilots drop more supplies, this time successfully.

23 June – Swedish pilot Lundborg forcibly removes Nobile from the ice floe but crashes his plane on the return for more survivors and is trapped with the others. Rescue operations suspended pending arrival of suitable light aircraft capable of landing on the ice.

6 July Lundborg is picked up from the ice floe by his Swedish co-pilot Birger Schyberg in a light Cirrus Moth ski-biplane. Schyberg intends to rescue the other five persons as well, but changing ice conditions lead him to change his mind after having brought Lundborg to safety.

12 July – The Soviet icebreaker Krasin rescues Mariano and Zappi, who were located from Krasin’s large aircraft the previous day. The five remaining Italia survivors are rescued by the ice-breaker later the same day.. Soviet pilot Boris Chukhnovsky and his four crew also rescued by the Krasin on its way back to Kings Bay. It had made an unsuccessful safety landing after seeing Zappi and Mariano.

14 July – Rescuers Sora and Van Dongen rescued from Foyn Island by Finnish and Swedish aircraft.

The causes of the crash remain controversial even today. The severe Arctic climate and decision to head back to base in the teeth of a worsening gale, rather than continue across the Pole to attempt a landing in Canada, was the main cause.

Another factor is the decision to let the airship rise above the cloud layer, causing heating and then expansion of the hydrogen, which triggered automatic valving of the gas. Once the engines were restarted, the ship dived through the cloud into freezing air again and, either because the automatic valves were jammed open, or because the ship had already lost too much gas above the clouds, it could no longer stay aloft. Although Umberto Nobile was the victim of a smear campaign after the crash, one criticism of him, from the master airship pilot Hugo Eckener is perhaps justified — that Nobile should never have climbed above the cloud layer in the first place.

In his book Dr. Eng. Felice Trojani, one of the airship engineers reported that in the years after crash, he examined 11 different possible causes in detail without coming to any real solution.

Gas capacity: 18,500 cubic metres/654,000 cubic feet

Power plant: 3 Maybach 560 kW/750 hp total

Length: 105.4 metres/347.8 feet

Diameter: 19.4 metres/63.9 feet

Performance: 112.3 km/h /70.2 mph

Payload: 9405 kg/20,900 LB

The Russian “Dirizhablestroem” was staged with developing the production of semi-rigid airship types. In order to speed up the execution of the tasks, in 1932 in the Soviet Union invited Italian Umberto Nobile, who was to head the technical management of the project.

For the base design USSR B-6 was to take Italian airship of the N-4, with the introduction of a number of its design improvements.

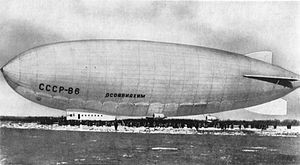

SSSR-V6 OSOAVIAKhIM (Russian: СССР-В6 ОСОАВИАХИМ) (Osoaviachim – Aircraft and Chemical Industries Assistance Society) was a semi-rigid airship constructed as part of the Soviet airship program, and designed by the Italian engineer and airship designer Umberto Nobile. The experience gained during the B-5 construction, and operation was the basis for the construction of the largest airship in the USSR-6 “Osoaviakhim.” The assembly lasted for 3 months and tha airship was named after the Soviet organisation OSOAVIAKhIM. V6 was the largest airship built in the Soviet Union and one of the most successful, first flying on 5 November 1934, piloted by Nobile, for 1 hour 45 minutes.

In October 1937 it set a new world record for airship endurance of 130 hours 27 minutes under command of Ivan Pankow, beating the previous record by the German airship Graf Zeppelin.

In February 1938, a Soviet Arctic expedition led by Ivan Papanin became stranded on the drifting ice pack. It was decided to send the V6 on a rescue mission, starting from the city of Murmansk. The flight between the airship’s base at Moscow, and Murmansk would serve as a test of the behavior of the airship in an Arctic climate.

During the flight, at approximately 19:00 on 6 February 1938, the airship collided with the high ground near Kandalaksha, 280 km south of Murmansk. Of the 19 people on board, 13 perished. The official version of the accident determined that the “pre-revolutionary” chart being used had the wrong altitude marked on it. An unofficial version suggests instead that the crash was jointly due to the old charts, poor visibility, and human error. Supposedly, the commander Nikolai Gudovantsev ordered the airship to gain altitude and rise to 800 m, but it was too late, and the ship struck the mountain around the 300-metre mark.

The crew of V6 are buried in the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow. The incident was a severe blow to the Soviet airship program. In 1968 a monument was erected on the crash site by local authorities.

Engines: 3 × Piston engines, 140 kW (190 hp) each

Volume: 19,400 m3 (685,000 ft3)

Length: 105 m (344 ft 6 in)

Diameter: 20 m (65 ft 7 in)

Gross weight: 12,000 kg (26,400 lb)

Useful lift: 9,300 kg (20,460 lb)

Maximum speed: 93 km/h (58 mph)

Crew: 15

Three engine airliner for nine passengers, 1925

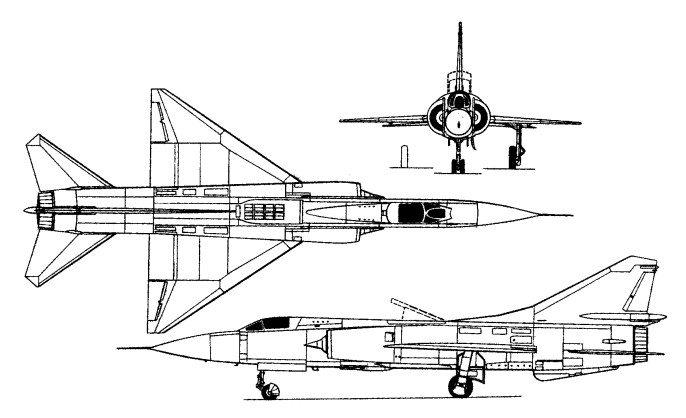

One of two parallel studies to meet a VVS requirement for a new frontal fighter capable of operating from small, austerely-equipped forward bases, the MiG-23PD – Pod’yomnye dvigateli, or, literally, “lifting engines” – or 23-01 was first flown on 3 April 1967. Featuring a 57° delta wing planform fundamentally similar to that of the MiG-21 but scaled up 73.6%, the MiG-23PD alias 23-01 featured auxiliary lift engines close to the CG. Two 2350kg Kolesov RD-36-35 engines were accommodated by a bay inserted in the centre fuselage and provided with a rear-hinged and louvred dorsal trap-type intake box and a ventral grid of transverse louvres deflecting the jet thrust during accelerating transition. A similar arrangement had been tested by the OKB in the previous year with the MiG-21PD test bed, which, with a 90cm fuselage lengthening aft of the cockpit and two RD-36-35 lift engines, had entered flight test on 16 June 1966. The primary power plant of the MiG-23PD was a Khachaturov R-27-300 of 5200kg and 7800kg with afterburning, and air was bled from the last compressor stage for flap blowing, the combination of lift engines and blown flaps reducing take-off distance to 180- 200m. Armament consisted of one 23mm GSh-23 cannon and two AAMs – one radar-guided K-23R and one IR-homing K-23T. Flight test continued until the autumn of 1967 when further development was discontinued in favour of the parallel MiG-23-11.

Engine: 1 x Khachaturov R-27-300, 5200kg – 7800kg with afterburning

Max take-off weight: 18500 kg / 40786 lb

Wingspan: 7.72 m / 25 ft 4 in

Length: 16.80 m / 55 ft 1 in

Height: 5.15 m / 16 ft 11 in

Wing area: 40.00 sq.m / 430.56 sq ft