Boeing’s vision of a futuristic regional airliner, the model 417, emerged in the years following WWII.

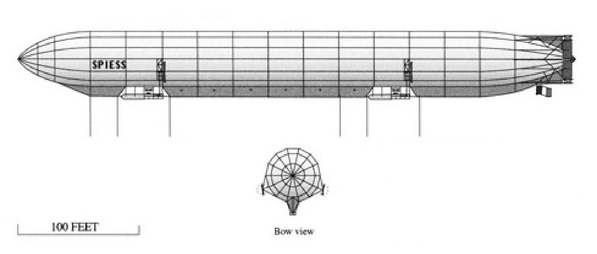

Boeing took a fresh look at the travel requirements of a postwar populace and identified a need for a smaller airliner to serve regional routes. In 1946, it came up with the 417, an 18,365-pound, twin-engine aircraft designed to carry 20-24 passengers at a speed of 200 mph.

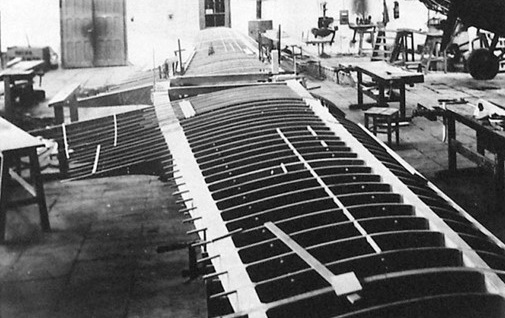

Boeing chose the 800 hp Wright Cyclone C7BA1, essentially the same powerplant as the R-1300 used by the North American T-28 Trojan trainer.

The Boeing appeared more advanced than the competing DC-5, but the performance numbers were nearly an exact match with the exception of the 417’s short-field performance, which was notably optimistic. The 417 was claimed to require only 1,200 feet to clear a 50-foot obstacle and 1,735 feet very impressive performance for its size and weight.

Proposed performance on the ground was similarly impressive, with features that were said to enable turnaround times of six minutes or less.

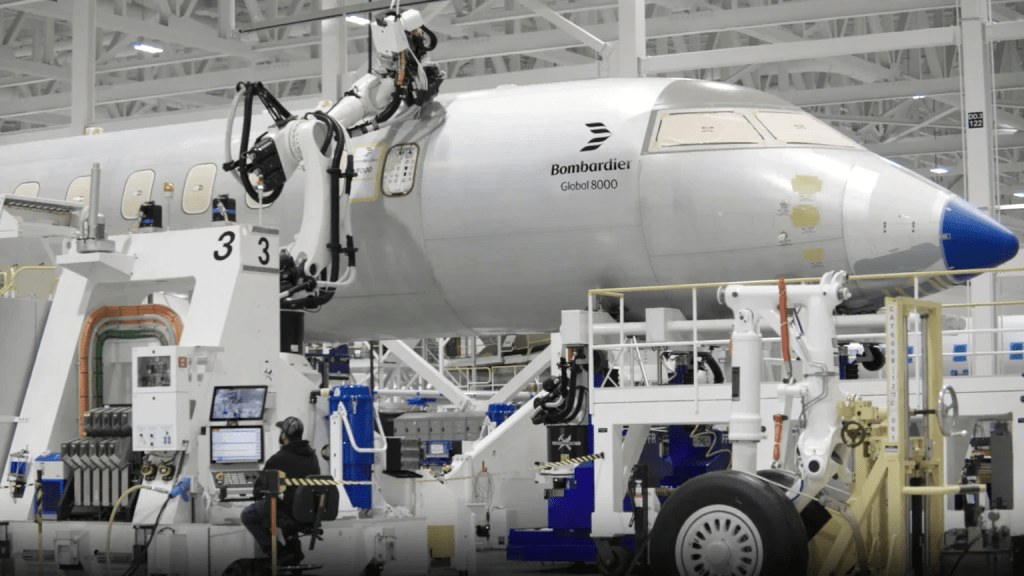

Boeing claimed this was achievable through the aircraft’s independence from ground equipment. The airstair door enabled boarding without the need for separate stairs, and the height of the cargo hold floor was said to match the height of truck beds, eliminating the need for ramps or hoists. In this diagram, we see the aircraft being refueled with the right engine running as cargo is loaded and passengers begin to board.

Presenting the concept to potential customers like Pan Am was one thing. Boeing also released data and artists’ renderings to the media, and it became prominently featured on magazine covers.

Boeing even ran its own ads in various publications.

Boeing did secure at least one order for the 417 when Empire Airlines ordered three of them to replace their Boeing 247s. In the September 1946 issue of Boeing Magazine, the 417 was said to provide a 57 percent greater break-even load factor than the 247D, promising greater profitability with fewer seats filled.

Just as Boeing was presenting the 417 to customers, Convair was doing the same with its 107, albeit without such a strong marketing and promotional effort.

While both concepts were forward-thinking solutions to shorter, lower-capacity routes, their roles would ultimately be filled with the glut of surplus aircraft from the war effort—namely, the DC-3, which provided similar performance for pennies on the dollar.