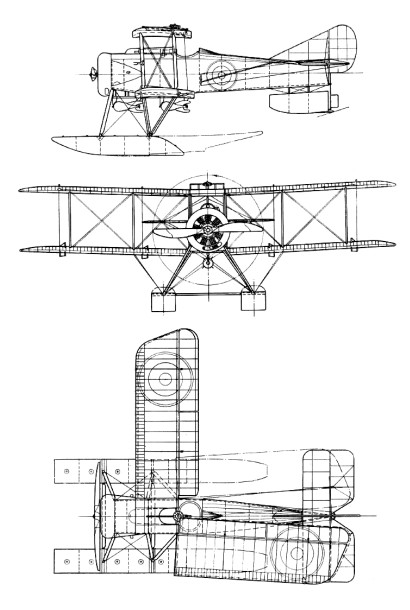

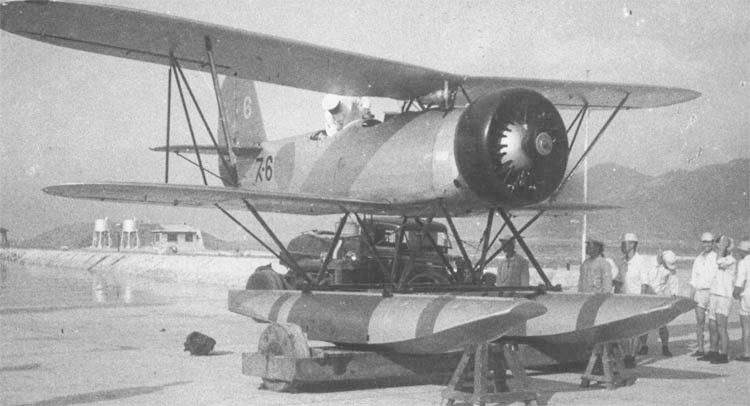

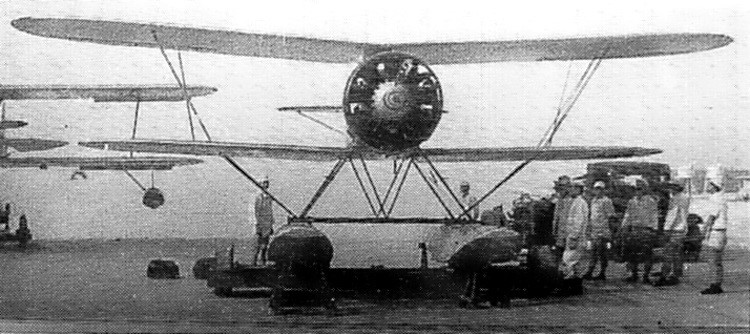

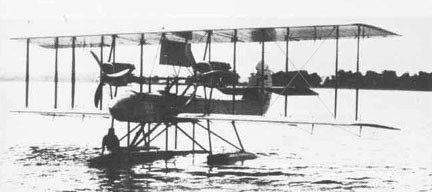

Westland Aircraft began design of its first aircraft in 1917, in response to an Admiralty requirement for a single-seat fighting scout seaplane. In the Admiralty’s N.1B category, the aircraft was designed by Robert Bruce and Arthur Davenport, and was a compact two-bay equi-span biplane of conventional wooden structure and fabric covering. First flown in August 1917, it was powered by a 150hp Bentley BR1 rotary engine. Inboard of the ailerons, on both upper and lower wings, the trailing-edge camber could be varied to obtain the effect of plain flaps. The wings could be folded backwards for shipboard stowage. Armament comprised one synchronised 7.7mm Vickers gun and a flexibly-mounted Lewis of the same calibre above the upper wing centre section. Two prototypes were built and sometimes referred to as the Westland N16 and N17 from their RNAS serial numbers. The first was flown with short Sopwith floats and a large strut-mounted tailfloat whereas the second was used to evaluate long Westland floats that eliminated the need for a tail float. This second aircraft, which lacked the camber-changing mechanism on the wings, also flew with the Sopwith floats and a tail float directly attached to the underside of the rear fuselage. By the time the N.1Bs were on test at the Isle of Grain, the RNAS was experimenting successfully with the shipboard operation of wheeled aircraft and the requirement for a floatplane fighting scout faded away.

Westland N17

Max take-off weight: 897 kg / 1978 lb

Empty weight: 682 kg / 1504 lb

Wingspan: 9.53 m / 31 ft 3 in

Length: 7.76 m / 25 ft 6 in

Height: 3.40 m / 11 ft 2 in

Wing area: 25.83 sq.m / 278.03 sq ft

Max. speed: 175 km/h / 109 mph