Syracuse NY.

USA

Built the New Standard D-31 in 1941

Syracuse NY.

USA

Built the New Standard D-31 in 1941

The 1943 Carolina Corp Model 1 NX15566 three-place cabin monoplane powered by two Franklin 4AC-199 was experimental for possible military use. The registration was cancelled in 1951.

The 1941 Ariel B and Ariel C (ATC 2-580) were then same as the model A with 75hp Continental and 80hp Franklin, respectively.

Two were finished, including N32459, of six begun.

It is unclear if the 80hp was that reported C model—references found only mention “two B models flying”—or if it might have been one of those unfinished planes.

The firm opted for the bicycle business instead.

Nakajima Hikoki Kabushiki Kaisha

From its foundation to the establishment (1917 – 1932).

In 1917, Chikuhei Nakajima (33 years old at that time), who retired as Engineering Captain of the Navy, contemplating developing a public aircraft industry, set up the “Airplane Institute” at Ojima Town close to Ota Town in Gunma Prefecture (currently Ota City). The building was a simply remodeled sericultural hut along the Tone River. In the beginning, there were only nine members, but in the following year they built their first airplane; the first “Nakajima Type 1” with a U.S.A. made engine. But the first Type 1 sadly crashed after take off. The second Type 1 also failed, and the third one finally did take off, but hit a ditch upon landing and also crashed. In that age, it was said that there was a pasquinade in Ota Town, “Too much paper money, too high a price for rice. Everything goes up, except Nakajima planes”.

After the trials and tribulations in the foundation period, the sixth Nakajima Type 4 was finally completed, and flew over Ojima Town proudly.

In 1919, the first mail plane contest was held between Tokyo and Osaka. Nakajima Type 4 cleared the distance in 3 hours and 18 minutes, and defeated the imported planes. Together with the prize money of 9,500 yen, it provided a good opportunity to demonstrate their engineering superiority to the public. The person who instructed this project both in engineering and management was Jingo Kuribara. He was not a flashy person but rather shy. A born engineer, he studied hard and his intellect captured the era. Kuribara at that time was General Manager of the Donryu Factory, and also General Manager of the Ota Factory. He played a leading role in developing later Nakajima Aircraft. In the management of the Institute, Kuribara exerted his energy to find the most competent people.

In 1920, the military having noticed drastic progress in aircraft technology during World War I in Europe, invited a training team from France and also started to seriously study licensed production of airplane bodies and engines. Nakajima Aircraft dispatched Kimihei Nakajima to France for a long period in order for him gather information and technologies regarding airplanes. With this as a turning point, Nakajima Aircraft received a large order from the military, and tremendous growth followed.

In 1922, the first all-metal airplane, Nakajima Type B-6 was completed. It was modeled after the Breguet 14. The Type B-6 and named “Kei-Gin Go (light silver)” since the revolutionary light weight metal at that time, duralumin, was used. It was revealed at the “Peace Memorial Tokyo Exposition” and got high reviews.

In 1922, Ichiro Sakuma was looking in the suburbs of Tokyo for the site of an exclusive airplane engine factory, and found one at Kamiigusa, Iogi, Toyotama-Gun (Ogikubo). He bought an area of 12,540sq.m the next year. Construction started immediately, and the Tokyo Factory was finished in 1924 and began to license and manufacture water-cooled Laurence engines. Separate working environments (engine production in Tokyo and body production in Ota) were established at that time.

From the Taisho Era to the Showa Era there was substantial progress in engineering due to the introduction of foreign technologies. In 1927, a competition was ordered by the Army to create the next generation fighter plane. Mitsubishi Internal Combustion Engine Co., Kawasaki Ship Building Co., Ishikawajima Aircraft Co. and Nakajima Aircraft Industries all participated. In 1928, Nakajima produced an airplane with a single high-wing with struts, named Type NC. In comparison with Mitsubishi and Kawasaki, which applied German style, water cooled, straight-line-based rugged designs, Nakajima Type NC had a streamlined and slender body with an air cooled engine. It resembled the Nieuport Delage in France, and at a glance, seemed nimble and agile. All Nakajima planes were designed with flowing elegance as tradition, and it was said that there was a common understanding among the engineers that “Real things (airplanes) reaching the pinnacle of engineering excellence should be beautiful” (The picture below shows Type NC No.7)

The engine of the Type NC airplane was changed with a Nakajima Jupiter 7 type, a Taunend type cowling was attached, and the entire body was refined with great effort. The plane was then adopted by the Army as the Type 91 fighter.

At that time, the Navy was studying 1928 Boeing 69B fighters and 1933 Boeing 100D fighters, but Nakajima was developing an original fighter named NY Navy Fighter independently to surpass those imported planes. The N of NY stood for Nakajima and Y was for the name of the chief engineer, Takao Yoshida. The airplane being developed was utilizing the Jupiter 7 of English Bristol Bulldog family, and was called the “Yoshida Bulldog” but was not adopted by the Army. Nakajima then replaced the chief engineer with Jingo Kuribara, and changed the engine to a newly developed Nakajima “Kotobuki (auspicious)”, and the “NY-Kai (NY-II)” was completed in 1932. The marked improvement in its performance was acknowledged and it was adopted as the Type 90 carrier fighter. At the dedication and naming ceremony in Haneda, the name “Hokoku (patriotic spirit)” was given, and together with other planes from Yokosuka Airforce, it demonstrated formation aerobatics. Among them, famous aerobatics performances made by the master trio of Genda, Okamura and Nomura were given, and they later became to be known as the “Genda Circus”. From here on, Nakajima quickly rose to fame and later monopolized of the production of Army and Navy fighter planes.

Organization of Nakajima Aircraft Ota Factory

Engine development at Nakajima 1923 – 1945

Mr Nakajima, who was playing an active role in the development of domestic technologies, started building

Even though Nakajima Aircraft was born in Ota, Gunma, Chikuhei Nakajima decided that “The factory should be in Tokyo in order to recruit top-class personnel” and dared to separate body and engine production by the Tokyo Factory (at Ogikubo) in 1924 in pursuit of domestic production of airplane engines selecting a site in the Tokyo suburbs.

Grand masters of aircraft body engineering at that time were said to be rivals, “Tukagoshi for the Zero fighter at Mitsubishi”, and “Tei Koyama at Nakajima”. The engine at Nakajima was master minded by “Ichiro Sakuma of Nakajima Engine”. Sakuma had studied internal combustion engine design on his own while working at the Yokosuka Naval Arsenal, and was selected as the first young engineer to be recruited by Mr. Nakajima when establishing the Airplane Institute after his retirement.

In the beginning, partially due to the Navy’s instruction, Nakajima produced a water cooled V-type 400PS engine that was licensed by Loren, France. Then, 127 units of the same W-type 450PS engine were produced until 1929. Loren Dietrich was an automobile manufacturer with a great history and entered airplane engine production in 1915, one year after World War I started. They started with a straight six, water cooled 100PS engine, then produced the Type 15, 275PS engine that was installed in a 2-seater Spud airplane. The engine got high reviews because of its excellent reliability. The Loren engine, made by Nakajima, was installed in the Nakajima Breguet 19A-2B reconnoiter carrier planes and the Type14-3 reconnoiter carrier planes, but the appearance of the engine with its exposed valves was not as attractive as the Hispano-Suiza.

Not very long after Loren production started, Nakajima eyed the newest product from Gloster in England – the Gamecock fighter plane, and judged that its radial engine was becoming main stream. He then acquired a manufacturing license of the air-cooled 9-cylinder radial engine, Jupiter, from Bristol in England in 1925. Air cooled engines at that time were using radial cylinders rotating together with the propeller, but Nakajima overheard that an engine with good cooling capability with fixed cylinders was being developed in England. The Jupiter engine was ahead of its time and already utilized the most advanced technologies such as an automatic adjustment device for tappet clearance, spiral piping for even intake distribution, and a four-valve intake and exhaust system. In 1927, after inviting two production engineer instructors from the Bristol company, Jupiter Type 6 420PS and Type 7 450PS with a turbo charger were put into production. 150 units of the Type 6 engine were installed in Type 3 fighter planes and Nakajima Fokker transport planes. In addition, about 350 units of the Type 7 engine were installed in Type 91 Army fighter planes.

At that time, airplane engines were segmented into three groups; Jupiter of Nakajima (air cooled), Hispano-Suiza of Mitsubishi (water cooled) and BMW of Kawasaki (water cooled), and the Nakajima’s far-reaching wisdom was way ahead of the others. Later on, about 600 units were produced including the Type 8 and 9 engines.

The Loren engine design instructor, Moreau from France, lived in a Japanese rooming house and delivered a series of lectures in other companies and schools. He adopted himself to Japanese culture, but the other instructor, Burgoyne from Bristol in England, continued to live like a British gentleman. Burgoyne hated the smell of Takuan (Japanese yellow pickled radish). He stayed at the Imperial Hotel, and it is said that he got off the train at Ogikubo, one station before Nishiogikubo (the closest station to the company) because there was a pickle shop in front of it.

Nakajima Jupiter Type 6

Air cooled, total displacement of 28.7 litters

Take off power: 420PS at 1500rpm

Weight: 331kg

Using this engine, the product nationalization plan was carried out gradually. By studying an air cooled 9-cylinder radial engine (the American Wasp), the first originally designed air cooled 9 cylinder, (the 450PS “Kotobuki” engine) was completed in 1930. Jupiter was made based on artisanry engineering, and the productivity was not good. As an example, the cooling fins were formed by machining. Nakajima then tried to combine good points found in Jupiter design with the rational design of the US made Wasp. On this occasion, Nakajima engineered four engine types, AA, AB, AC, and AD as engineering exercises, but they were never manufactured. The next engine design, AE, was highly innovative with a bore of 160mm and a stroke of 170mm. Prototypes were made and performance tests were done, but this was not adopted due to its too venturous engineering. In 1929, the AH with bore/stroke of 146/160mm and a total displacement of 24.1 litters was worked on. This was to be the final version of the engine design and failure would not be tolerated, The engineering was based on a principle of solid, simple and clear construction. In June 1930, the first prototype was completed, and passed the durability test for the type approval in the summer. Then flight tests were started using a Type 90 reconnoiter carrier plane in the autumn. In December 1931, this engine was approved and adopted by the Navy. It was then installed in Type 90 reconnoiter carrier planes, Type 90 carrier fighter planes, and the famous Zero fighters of Mitsubishi. In the beginning, the Army did not show any interest in this engine being developed through the Navy instruction as usual, but later adopted it as Ha-1 Ko engine used in Type 97 fighters, and had little choice but to recognize its superiority.

The engine was named, in connection with Jupiter, “Kotobuki” which pronounced “Ju” in the Chinese-style pronunciation of the Kanji. Since then, Nakajima was using a single Kanji (Japanese character) to bring luck to the engine names. Mitsubishi used star names, and Hitachi used wind names as well.

Nakajima engines were widely used not only in warplanes but in civilian planes as well. About 7,000 units for civilian use were produced up until the end of the war.

In the Army they named aircraft engines by type codes such as Ha-25 or Ha-112, while in the Navy, they used nicknames such as “Homare (honor)” or “Kasei (Mars)”. At Nakajima, as mentioned before, a single Kanji, (Japanese character) carrying good luck such as “Kotobuki(auspicious)”, “Sakae (glory)”, “Mamori (guard)”, or “Homare” was used. Mitsubisi used star names such as “Kinsei (Jupiter)”, Hitachi used wind names such as “Ten-pu (wind in the high sky)”

The “Kotobuki” engine was improved further and developed into the “Hikari (light)” engine with a bore and stroke expanded to the limit of the cylinder (160×180mm to get a displacement of 32.6 litters) and the power was increased to 720PS. “Hikari” was used in Type 95 carrier fighters and Type 96 No.1 carrier attackers. In 1933, a 1,000PS class, Ha-5 prototype was completed, which utilized the bore/stroke of “Kotobuki” and a double line 14-cylinder. The further improved Ha-5 was developed into the 1,500PS, and about 5,500 units were produced.

At the same time, an engine was developed upon the Navy’s request called “Sakae”, of which the Army name was Ha-25 (crick here for details). This engine was uniquely engineered as an engine of small size, light weight, and high performance in small displacement and fewer cylinders. This was then installed in Type 97 carrier attackers, Type Zero carrier fighters, “Gekko (moonlight)” Type 99 twin engine light bombers, and also the famous Type 1 “Hayabusa (falcon)” fighters. This engine was mainly produced at the Tokyo Factory and at the Musashino Factory (built in 1938 and later became the Musashi Factory after merging with the Tama Factory), and more than 30,000 units were produced (the highest number in history).

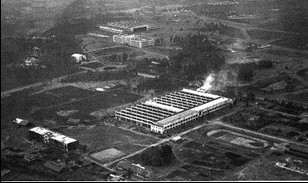

The Musashino Factory was an exclusive factory for the Army engines, and this modern factory, with an area of 660,000m2, was the crown jewel of Ichiro Sakuma’s outstanding knowledge and labor. Ford’s state of the art assembly line operation and the scientific management process of Taylor system were incorporated. In addition, production process, the material flow, and human movement were carefully thought out. A welfare program for employees and first-class facilities were second to none at that time. The Navy was impressed by this, and requested the same kind of exclusive factory be made for them. The Tama Factory was built next to the Musashino Factory in 1941. Later, due to the aggravation of the war situation, Nakajima proposed to unite the both the Army and Navy factories for more efficient operation, but because of hostilities between them, they did not come to an agreement for several years until they were merged into the Musashi Factory.

Ichiro Sakuma, who took an active role in Nakajima engine engineering for each plant, also planed and established the Mitaka Research Center, and worked as General Manager in the Construction Department. The intention of the Mitaka Research Center was not only the aircraft research but also to establish a general research center for politics, economics and engineering. Considering this to be a far-reaching program for the future of Japan, a land mass surprising 1.65 million square meters was secured. Coincidentally the ground breaking ceremony was held on the 8th of December 1941, the day Japan entered World War II. But later, due to an aggravation of the war condition, the military was against having such an elaborate research center, and the facility started its operation as a prototype engineering division and prototype manufacturing plant in 1943. (After the war, almost all of its facilities were sold. The main engineering building is now utilized as a schoolhouse of International Christian University.)

As a result of the outbreak of World War II in Europe in 1939, the engines developed in Europe and the US moved toward 1,500~2,000PS class. Because of this, Nakajima formulated a plan to modify “Homare” into an 18-cylinder engine. There were piles of problems in various engineering fields, but with strong support from the Navy, the unique, small, light weight, and high-power “Homare” prototype was completed. Compared with the Mitsubishi engine “Kasei”, which had an external diameter of 1,372mm, “Homare” was only 1,180mm in diameter, and brought with it high performance for a plane in which a smaller frontal sectional area was a key factor. This made it possible to develop masterpiece airplanes such as the “Hayate (gale)” and the “Saiun (iridescent clouds)”. “Homare” was installed not only in Nakajima planes but also in the bomber “Ginga (galaxy)” and other planes such as the “Shiden (purple lightning)”, the “Shiden-kai (Shiden-II)”, and the “Ryusei (meteor)”, and boasted its exceptionally high power in the world at that time. But because of the war condition, it became difficult to acquire high quality fuel that was required for the engine, maintain the quality level of machining process (due to a lack of skilled workers), and purchase special steel materials. As a result, its performance potential was not fully realized before the end of the war.

“Homare (honor)” Type 21 (Ha-45-21)

Air-cooled double radial 18-cylinder, Total displacement: 35.8 litters

Take-off power: 2,000PS at 3,000rpm

Weight: 830kg

External dimension: Overall length; 1,785mm, External diameter; 1,180mm

Total production: 8,747 units

1930 – 1936 Birth of Nakajima’s Crowning Work

Nakajima Aircraft was expanding continuously, and reorganized itself in 1931 by forming the partnership firm “Nakajima Aircraft Industries Ltd.”, using a capital of 6 million yen. In 1934, a new large-scale factory was completed in the central part of Ota City in Gunma Prefecture and its headquarters was set there. The area was 45,000 tsubo (150,000sq.m). The then modern, three-story main building in the front (now being used as the current Gunma Manufacturing Division of Fuji Heavy Industries Ltd.) was designed in the shape of an airplane as seen from a bird’s-eye view. In this building, the Engineering and Development Department was located on the third floor.

From the east entrance, the Navy plane engineering group was located on the left. Chief Engineers (Mitake, Akegawa, Fukuda, Inoue, Yamamoto, Matsubayashi and Nakamura) sat down in the middle of the room and delivered their ideas while issuing instructions to the drafting engineers located on both side of them. Proceeding further to the west of the building, passing through the middle hall, there was the Army plane group where Chief Engineers (Koyama, Mori, Nishimura, Matsuda, Ota, Aoki, Ichimaru, Uchida and Dodo) sat down. Though they were the top echelon of the group, all of them were youngsters between the age of 25 to 35, almost fresh from school. Back then, jobs were done through a project team that was organized for each plane, and all members handled all areas of engineering, such as body construction, electric equipment, and armaments. But separate groups were designated for aerodynamics and weight. Hideo Itokwa, who became famous in a rocket science after the war, was in the aerodynamics group.

This period was the best time for the young engineers with a climate for challenging innovation freely and openly. There were a bunch of brave engineers, especially within the Navy plane group, many of whom graduated from Aeronautics of Tokyo University. All of them were hot and daring young men with strong personalities. On the other hand, the Army plane group had mainly graduates from Tohoku University such as Tei Koyama and Jingo Kuribara. They were as calm, cool-headed, and Spartan, but in other words, they were a very square and conservative engineering group. (Professor Hideo Itokawa said at a lecture after the war that “Mitsubishi is characterized by organization, while Nakajima is characterized by personality”.)

These engineers worked together around the Senior Chief Engineer and had liaison meetings to establish lateral communication. They also formed Gishi-kai (senior engineers association). This Gishi-kai was occasionally more powerful than the member of the board meeting of the company, and sometimes rejected the decisions made by the board. For this reason, many people relied heavily on this group. But there was still some competitive feeling between the Army group and the Navy group. Both engineering groups would often play a friendly game of “Go” at lunch time, but avoided talking about the content of their work. The engineers supporting the Gishi-kai were only high school or technical school graduates from the Kanto or Tohoku region, but all of them were first in their class and very capable engineers.

In accordance with government principles to increase aircraft production, the Ota Factory was greatly expanded, and the Musashino Factory was established solely for Army engine manufacturing in 1938. The Navy was influenced by this and issued a command to expand the Navy factory independently. The Tama Factory for engine production and the Koizumi Factory (current Oizumi in Gunma Prefecture, shown in the picture) for body construction were built in 1940. The Koizumi Factory was the largest in the Orient with an area of 1,320,000m2, and produced mainly “Zero” fighters (engineered by Mitsubishi) with Nakajima “Sakae” engines. Also other planes; the “Gekko (moonlight)”, the “Ginga (galaxy)”, the “Tenzan (Tian Shan, Chinese mountains)”, the “Saiun (iridescent clouds)” , and others totaling about 9,000 units were manufactured at the plant. The number of employees there, in the end, totaled more than 60,000. Every time a plane was completed, its large door (30m in width, more than 15m in height) was opened and all employees would see it off by singing the national anthem and the company song at a ceremony. (Later this custom was banned by the military in order to prevent espionage.) The engineering division moved out from the third floor of the main building in the Ota Factory. The Army plane group moved to a newly built three-story building adjacent to the main building, and the Navy plane group moved to the Koizumi Factory. Developmental organization was changed from an one-plane/one-team method to a specialized group method that focussed on each function separately, such as an Aerodynamics Team, a Weight Team, a Structure Team, a Power Unit Team, a Landing Gear Team, a Control Team, an Electric Equipment Team, an Armaments Team, etc. Also a Total Management Team was established to promote standardization for a more efficient development process. Nakajima proposed again and again to standardize the Army and the Navy parts, but due to their egos, neither the Army nor the Navy compromised, and Nakajima had to put up with the inefficiency. (Separate page: Vicissitude of Nakajima Body Plant)

When a manufacturing order for a new plane prototype came form the military, The Aerodynamics Team established the basic concept, the Weight Team set the target value, and a three-view drawing was made. It was then circulated to other teams. More often than not, the Structure Team initiated a debate that “It is impossible to make a plane with the weight specified by the Weight Team”. Through the heated discussions of what is “Possible” and “Impossible”, the target value was more or less achieved in the end. In those days, there were no computers, and all they had to work with were slide rules. The slide rules they used were much longer than normal, having a length of 50 to 60cm. They boasted that “Samurai wear Katanas, but we wear Slide-rules!” They always carried a small slide rule in their chest pocket. The accuracy of slide rules was more than sufficient, considering the manufacturing allowance. But when precision was required, they ran a Tiger-calculator (a manual calculating machine that does multiplication or division by repeating addition or subtraction) from morning till night. (Engineer, Mr. Aoki said.)

Evaluation tests for Army approval were normally done at Tachikawa Airfield. Just after the test, the pilot who finished the test flight stood in front of the senior officer and reported the results loudly with a salute. On the side, Nakajima engineers would listen to the report carefully, and worked out remedies instantly on the spot. Then they would call Ota to gather all the necessary personnel, and drive back to Ota through Kumagaya, crossing the Tone River. The necessary parts were manufactured through the night and many a time, they were seen driving back to the site early the next morning with a horizontal stabilizer lashed down on the roof of the car. They often would install the new parts just in time for the tests. But the most exciting event was when their airplane was evaluated against other competitors in dog-fight tests or performance tests. The results were “Win!” or “Lose!” and all engineers were really enthusiastic and ardent about their work. The engineers in charge of developing a plane were strictly prohibited to ride as a rule, especially on the maiden flight, but it is said that they got on board occasionally to make confirmation tests in cold weather tests in Manchuria or hot weather tests in the south areas.

Although Nakajima Aircraft is famous in the field of combat aircraft, the production of civil aircraft is hardly mentioned. One of Nakajima’s most highly important civilian aircraft was the AT-2 passenger transport plane. Even though its basic design was based on that of U.S.A. DC-2, its construction was very innovative. It was named AT (Akegawa Transport) after its chief engineer, Kiyoshi Akegawa. The first AT made its maiden flight successfully at Ojima airfield. From that point on, improvements were taken over by Chief Engineer, Setsuo Nishimura, and the AT became an excellent mid-class passenger plane with superior performance with regard to controllability and stability. This plane was used by Japan Airlines before the war and was sometimes named “Asama”, “Kashima”, “Hakozaki”, “Kumano”, or “Izumo” after the famous sightseeing spot in Japan. It was also adopted as a transport airplane by the Army.

Nakajima AT-2 passenger transporter

Overall width: 19.916m, Overall length: 15.30m

Gross weight: 5,250kg

Engine: Nakajima “Kotobuki” Type 2, Maximum speed: 360km/h

Range: 1,200km, Crew: 3, Passenger: 8

During Army and the Navy airplane competitions, the historic Type 97 fighter was born. It could be said that it is the most important achievement in Nakajima Aircraft’s history. At that time, there was a lot of controversy within the company regarding which wing type would be better, that of a biplane or a monoplane. The same debate applied to overseas airplane industries, and the trend, at that time, leaned toward a biplane putting more emphasis on dog-fight performance. With this situation at hand, Chief Engineer Tei Koyama, with the cooperation of young engineers such as Chief Engineer Minoru Ota and Hideo Itokawa, developed the “Ki-27”. It had an innovative body structure and a unique wing construction using a new wing shape with a straight front edge line, based on a new wing theory. This plane defeated ones manufactured by Mitsubishi and Kawasaki, and became the third Nakajima plane to be adopted.

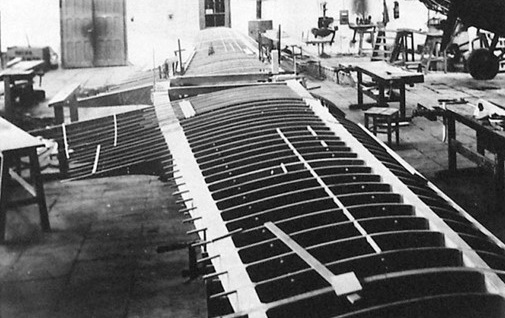

The Type 97 fighter excelled not only in the maneuverability due to its light weight, but also in maintainability. It established high utilization rate and achieved good results duaring the Nomonhan Incident and during the early stage of World War II. Its main wing was constructed into a single piece, made separately from the body, and assembled later. This improved the productivity greatly. At one time, a stream of new planes were supplied to the battlefront and no more pilots were available to fly the planes. The unique wing theory applied to the Type 97 fighter and all fighters made afterward.

From 1938 to 1942, a total of 3,386 Type 97 fighters were produced; 2,007 units by Nakajima, and 1,379 units by Tachikawa Aircraft and Manchuria Aircraft.

Reaching the very top, and the ebb tide 1936 – 1945

Besides the Type 97 fighter, the Type 97 carrier attacker was approved and adopted by the Navy in 1937. It was one of the world best plane as the first single engine Navy plane with retractable landing gear. The Type 97 carrier attacker was engineered under the direction of Chief Engineer, Katsuji Nakamura. The three seater had an all-metal monocoque body construction, hydraulic retractable main landing gears, Fowler flaps, and hydro/manual folding main wings. There were two types; the first version with a “Hikari(light)” engine and a later version with a “Sakae” engine. These planes became famous in the attack on Pearl Harbor, and a total of 1,250 units were produced. Japanese aircraft industries attained the world level in this kind of aircrafts.

Under an exclusive nomination by the Army, a development of the famous Type 1 fighter, the “Hayabusa (falcon)” (Ki-43) was started as the successor of the outstanding Type 97 fighter. the “Hayabusa” was engineered to achieve both exceptional maneuverability and long range. It became the ace of the sky. The “Hayabusa” production reached 5,751 units and became the second largest mass-produced plane, next to the Zero-fighter. But from the beginning, the “Hayabusa” did not run smoothly. The engineering group was the same as the one for the Type 97 fighter (Tei Koyama as the chief, Ota Minoru and Hideo Itokawa as the Engineers), but they were not very enthusiastic due to a medley of contradictions in the requirement. The first prototype was made in 1938 utilized 1,000PS class engine, and new mechanisms such as retractable gears and a variable pitch propeller. But to prevent an increase in weight, the wing loading became too high and as a result its dog-fight performance was disappointing. But the “butterfly-type dog-fight flap” developed at that time for an air-defense fighter Ki-44 (later “Shoki”) proved effective even on a plane with high wing loading. Together with this flap and an improved Ha-25 engine, the plane showed significant improvement in performance, and was quickly adopted. The “Hayabusa” not only boasted its nimble maneuverability and exceptional long range, but also had excellent neutral controllability and good serviceability. But there were several drawbacks; lack of rigidity of the main wing, trouble in the main landing gears, and problems mounting heavy machine guns on the wing due to its three-beam wing construction. Also, fighting strategy was shifting from using light-weight fighters to heavy fighters, and its lack of diving speed and poor high-altitude performance became its weakest points.

At almost the same time as “Hayabusa”, the Type 2 heavy fighter, the “Shoki (Japanese defense God)” was being developed. Since a large Ha-41 engine for a bomber was used, the plane had a unique big-head style. It tended to be avoided by pilots due to its poor visibility when landing, but it had good speed and received support from experienced pilots.

In 1941, the Army requested a plane that had maneuverability superior to the Ki-43 “Hayabusa” and speed and climbing power better than the Ki-44 “Shoki” be developed. It required a top speed of 680km/h, a climbing time of 4.5 minutes to 5,000m, and a range equal to that of the “Hayabusa”. This was a difficult demand to meet, even with the excellent performance of the Ha-45 engine “Homare”. Nakajima’s engineering team (the “Fighter’s Kingdom” that had developed the Type 97 fighter “Hayabusa” and the “Shoki”) took on this challenge by combining its all of its manpower. The Chief Engineer was Tei Koyama, and the team included Engineer Setsuo Nishimura, Masaru Iino, and Yoshio Kondo who was dispatched from the Army Aircraft Technology Institute. Nakajima called this Ki-84 the fastest fighter in the world, and completed the first prototype in March 1943. At the test flight it reached a maximum speed of 624km/h, but the type approval was delayed due to engine troubles, and finally adopted as the Type 4 fighter “Hayate (gale, swift wind)” and entered into priority mass production. Production totaled 3,499 units, third following the Zero and the “Hayabusa”.

The “Hayate” established an unmistakable position as one of the masterpiece planes. After the war, this plane was tested by the US military and clocked a top speed of 689km/h at 6,100m with 140 octane fuel. It also demonstrated exceptional climbing power, maneuverability, fire and bullet resistance, and firepower. It was confirmed the distinction as “the best fighter plane in Japan”.

Due to the ever-expanding production demand by the Army and Navy, Nakajima Aircraft opened new factories one after another from 1942 to 1944. Many plants were built rapidly such as; the Handa Factory in Aichi Prefecture for the Army planes “Tenzan” and “Saiun”, the Omiya Factory in Saitama Pref. for producing single engine planes for the Navy, the Utsunomiya Factory in Tochigi Pref. for “Hayate” planes for the Army, the Hamamatsu Factory in Shizuoka Pref. for engines for the Army, and the Mishima Factory in Shizuoka Pref. for accessories production. Also, construction on an under the ground plant was started in Shiroyama in Tochigi Pref. and the Kurosawajiri Factory in Kitagami City in Iwate Pref. for evacuation purposes, but they were not finished by the end of the war and had no practical use.

Although Nakajima was the “Kingdom” of a single-engine planes (mainly fighters), they also worked on multi-engine planes as well. One of them was the approved twin-engine heavy bomber “Donryu (the name of a Buddhism priest)”, which evolved into four-engine planes, the “Sinzan (deep mountains)” and the “Renzan (range of mountains)”. These were developed upon the Navy demand, but not completed due to the condition of the war.

In 1943, at the early stage of the war, Japan was optimistic due to its early success, but Mr. Nakajima worried about the enormous difference in industrial power and natural resources between Japan and the US. He also noted the trend in the airforce strategy of the US with his keen intelligence. He judged, from the development status of the B-29 and B36 at that time, that Japan would be attacked by the B-29 in the fall of 1944.

To counter this situation, Mr. Nakajima completed a large thesis entitled, “Strategy for Victory” in August 1943, proposing ways to change the current strategy and to retrieve the superiority in the war. He made 50 copies of the thesis, in confidence, and approached politicians and bureaucrats. The backbone of the strategy relied on an ultra-heavy bomber; the “Fugaku (Mount Fuji)”. Prior to the disclosure of the strategy, in early 1943, all Nakajima’s executives were called in and the concept of a new six-engine ultra-heavy bomber (Z-plane) was explained. An “Air-defense Research Workshop” was then started to promote the program.

Two versions of the “Fugaku” were studied at that time, and it was to be 65m in width, 45m in length, and 160ton in total weight – far larger than the B-29. It was to be a super giant plane, almost the same size as a modern Jumbo-jet. But it was too late and also there was not enough technology and power to built such a giant plane in Japan at that time.

Although the plan was an audacious dream from a practical standpoint, it is also true that this was the only way Japan could overturn the war situation.

In 1945, as air attacks on mainland Japan became intensified, the Government decided to nationalize aircraft manufacturers, such as Nakajima Aircraft, in order to continue production. In April, Nakajima was designated as the First Military Arsenal, and all of its 250,000 employees, including commandeered workers, students, and volunteer lady corps, were moved under the control of the military.

Each plant was exposed to the thorough air attacks by B-29s, and production capability was being wiped out. In August of that year, all airplane manufacturing was banned at the end of the war. Nakajima Aircraft, which worked almost exclusively for the military, was ordered to be dissolved.

Nakajima Aircraft was always watching the world, fostering young engineers, operating schools for youth at each of its factories. It also adopted fringe benefit programs such as sports clubs, which are still applicable even today.

Mr. Nakajima also eagerly studied foreign technologies and saw the true industrial power of the US. It is also said that he was basically against to enter the war.

The curtain came down on the eventful history of Nakajima Aircraft, less than 30 years since the Aircraft Institute began its voyage at a sericultural hut at Ota, Gunma Prefecture. It produced a total of 25,935 airplane bodies and 46,726 airplane engines.

Nakajima Aircraft’s total production in 30 years, in comparison with other manufacturers.

After the war, Nakajima Aircraft was dissolved by order of GHQ into more than 15 companies. Each factory began making products utilizing the air craft technology, such as monocoque busses, or scooters using bomber tail wheels. But five of the companies joined forces together again under the slogan “Aircraft again!” and merged into one company, currently known as Fuji Heavy Industries, Ltd (SUBARU).

Suzuka 24

By 1945 a new threat emerged to Japan, American strategic bombing raids. The introduction and use of the Boeing B-29 Superfortress posed a substantial threat to Japanese aircraft. To remedy this issue, development of new more powerful fighters took place. Correspondence with Germany resulted in sharing of rocket and jet engine information to Japan.

Rocket development became heavy in Japan, with multiple designs being built. It was decided to redesign the Ohka for a new role – bomber interception. The Ohka-based interceptor would be lighter in weight, smaller armament, and a small silhouette. The Ohka was designed by the Japanese Naval Air Service, however the change to use a land-based interceptor was developed by either the Navy or Army air serviced, currently unknown.

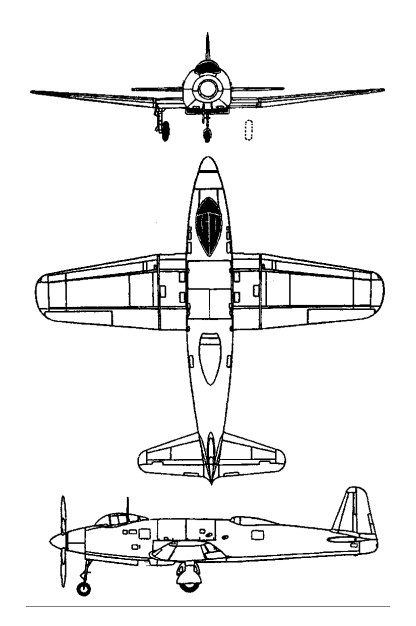

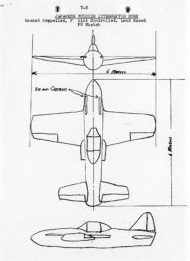

The Ohka 43B and Suzuka are two completely different machines. The new design removed the use of a warhead entirely. Instead, a fuel tank and two 20mm cannons were placed in the nose of the design. With only a length of 6 meters, the 20mm cannons take up a considerable worth of space to fit the gun and munition belts properly. The design of the aircraft was significantly altered to account for its new use. A changed tail design, now introducing a general vertical and horizontal rudder and elevator, allowing better control of the aircraft in flight. Along with this a longer wingspan, being 0.5 meters longer on each side of the aircraft and thicker support. The new design of the Ohka-interceptor allowed for ease of maneuverability in flight. It is speculated to have been powered by a Toko Ro.2 (KR-10) rocket. The engines for the Suzuka was one of the most important changes. The Suzuka would be powered by a single Toko Ro.2 (KR-10) rocket (Japanese copy of the Walter HWK 509A rocket used in the J8M/Ki-200 interceptors) producing around 14.7 kN (3007 lbf) of thrust. The fuel capacity accommodated an estimated 7 minutes worth of fuel.

The KR-10 by April 3rd were highly experimental. Even when mounted on the J8M prototype months later, the KR-10’s operated poorly and even resulted in exploding due to the rocket mixtures.

The interceptor was produced in a handful of models. By the time the war ended in 1945, most of the vehicles were kept at Suzuka (a single example), Yokosuka, and Kanoya airfields.

The Suzuka 24 would have been launched from a ramp, and is unknown whether or not it had landing gear.

It was allegedly seen in action 3 times near the end of the Pacific War by B-29 bomber crews, but did not inflict damage and retreated shortly afterwards.

The first encounter occurred on April 3rd of 1945 during a B-29 raid on the Tachikawa Aircraft Factory. A B-29 crew reported seeing a “ball of fire” at their 5 o’clock closing in behind them. The B-29 pulled quick evasive turning maneuvers while lowering their altitude. The “ball of fire” quickly closed in on the lost distance, but suddenly turned back a few seconds later. One of the crew members reported that he saw a stream of fire following the object, and faded when the object turned. The blister gunner reported seeing a wing attached to the object, and what seemed to be a navigational light burning on the wing’s left tip.

The second encounter occurred during a raid near Tokyo Bay. A B-29 crew member reported seeing a “ball of fire” following it at approximately 4,000ft (1,220m) while the bomber was at approximately 7,000ft (2,130m). The B-29 began evasive maneuvers right away, gaining and losing 500ft (152m) quickly. It also changed its course by 35 degrees, and increased the airspeed from 205mph (330km/h) to 250mph (402km/h). The B-29 crew lost sight of the “ball of fire” three times as it was flying through the clouds but to their surprise, found it sitting on their tail when the B-29 came out of the clouds. The “ball of fire” followed the B-29 for approximately 5 miles (8km) across Tokyo bay before turning around.

The third encounter supposedly happened at night, a waist gunner of a B-29 at 8,000ft (2,440m) reported seeing what was thought at first to be light from an amber colored searchlight. The light gained altitude and followed the B-29. The pilots then climbed to 12,000ft (3,660m) and then came down to 10,000ft (3,050m) but the light followed. The radar operator then picked up an object trailing behind the B-29 at approximately 1 mile (1.6km) behind. Shortly afterwards, the tail gunner reported seeing a stream of fire emanating from the pursuing object. The fire appeared to be coming out in bursts, with each burst measuring approximately 24 inches (61cm) with a 6 inch (15cm) break between each burst from the gunner’s perspective. The fire kept emanating for about 7 minutes before ceasing for good. The B-29 continued through evasive maneuvers, but the object kept on following. The object was last seen about 30 miles beyond the coast line above the ocean.

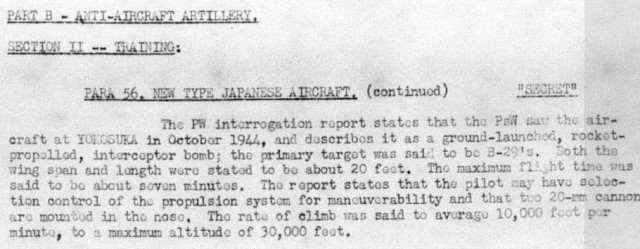

United States Intelligence discovered one model at Suzuka, and labeled the aircraft as the Suzuka-24 as the official designation was not known. The first such discovery was made by AC/AS intelligence when they photographed Suzuka Airfield.

Soon afterwards, XXI Bomber Command discovered four more models of the Suzuka-24 were discovered at Kanoya airfield. At Yokosuka, another model was found along with a pilot belonging to the airfield captured. The pilot listed details of the aircraft, its designated use being bomber intercepting, and measurements of the aircraft. Photographs were mentioned as being taken, however at this time none have been found. The machine was further described in detail in a prisoner of war interrogation with two Japanese petty-officers.

In an interview conducted post-war of two Japanese petty officers confirmed the existence of the Suzuka. One of the interrogates described seeing the Suzuka at Yokosuka airfield in October of 1944. He described it as a “ground-launched, rocket-propelled, interceptor bomb”. The primary target seems to be Boeing B-29 Superfortresses.

Reports on the Suzuka 24’s spotted from aerial photos, as well as information collected from POWs.

After the war, the United States encountered many different aircraft. Multiple variations of the Ohka were made and left over in mixed conditions. Because of this, the Suzuka-24 is confused to be an identical Ohka with a warhead, the Model 43B. The Model 43B was similarly designed to hold two 20mm cannons. However the fuselage was extended to carry both the cannons and warhead with fuel for a Ne20 jet engine.

Suzuka 24

Powerplant: 1x Toko Ro.2 (KR-10) rocket – 3,307 lbs / 1,500kg thrust (presumed)

Wingspan: 20 ft aprox. (6.097 m)

Length: 20 ft aprox. (6.097 m)

Maximum Glide Speed: 840 kmh (520 mph)

Rate of Climb: 10,000 feet per minute (3,050 meters per minute)

Range: 7 minutes of fuel

Service ceiling: 32,000 feet (9,755 meters)

Crew: 1

Armament: 2 x 20mm Cannons (60 or 150 shells per gun) (Unknown Ho-5 or Type99)

Bombs: None

Charles A. Zornes seems to have started aircraft construction in Walla Walla, Washington, USA, in 1909. After they trained at the Benoist Aviation school in St. Louis, he and Johnny Ludwig together with some associates set up a company in 1912 in Pasco, Washington to manufacture aeroplanes. He also ran a flying school there, with the 1912 headless pusher and at least two others. Zornes crashed on April 19 1912, with injuries that did not seem to be life threatening. He appears in some lists of aviation casualties after the accident, but it appears he might have survived and lived until 1954.

Designed by Horace Keane, the two place open cockpit low wing monoplane Libra-Det was built circa 1940.

Engine: 130hp Franklin

Wingspan: 33’4″

Length: 24’8″

Useful load: 480 lb

Max speed: 122 mph

Cruise speed: 108 mph

Stall: 55 mph

Range: 325 mi

Seats: 2

President: Harley L Clark

Lodi NJ.

USA

Circa 1940 airplane builder

In the first half of the 1930s. In Yugoslavia, the development of aircraft of its own design has become more active. The activities of Yugoslav designers could be seen in 1938 at the Belgrade Aviation Exhibition. Among the other planes there was a prototype of the R-1 bomber from Zmaj.

During 1936 at the Zmaj factory, Dušan Stankov, then technical manager, and George Dukic initiated the design and construction of a reconnaissance-bomber. After tests in the wind tunnel at Warsaw and acceptance by the Yugoslavian Air Force, the project was designated Zmaj R-1 (Serbian Cyrillic: Змај Р-1). The contract for the construction of the prototype was signed in 1937. The team of designers joining Eng. Djordje Ducić and a few young engineers who worked on the design completed the prototype before the beginning of a large aerospace workers strike in April 1940, with final assembly at the military part of the airport in Zemun.

Its design was mixed – Alclad monocoque fuselage and wooden wings and tail, metal construction rudders with fabric cover. The R-1 was equipped with Hispano-Suiza 14AB engines of French production, placed in gondolas under the wing. Flaps and landing gear was hydraulically operated. The composition of the crew varied depending on the purpose of the aircraft. In the version of the bomber R-1, the crew consisted of 4 people, in the variant of the attack aircraft – 3 people. The crew of three was accommodated in separate cockpits. Aiming and firing of the armament was made from the top cockpit while the bombing were performing from the front cockpit. The plane could take on board up to 1600 kg of bombs, and one large-caliber bomb could be placed on a special device in the fuselage for attack from a dive. The attack aircraft carried a smaller bomb load, but its small arms of two 20-mm guns and two 12.7-mm machine guns were much better suited for storming enemy troops. The two Oerlikon 20 mm cannon were in the fuselage sides but this was later changed and repositioned in to the wing roots. Two more 7.9 mm machine guns were placed in the nose top and one machine gun was placed in the rear fuselage for the defense.

The first flight was on 24 April 1940, pilotted by reserve Lieutenant Đura E. Đaković, a transport pilot with Aeroput. The initial testing justified all expectations in terms of aerodynamic characteristics and performance, unfortunately on the third flight the pilot was unable to lower the landing gear and had to land with the undercarriage extended, damaging the propellers and engines. Replacement parts for the propeller and landing gear were imported from Germany and France delaying repairs considerably.

The aircraft was rebuilt so that testing could be resumed at the end of March 1941, but in early April the bombing of Zemun airport damaged the prototype Zmaj R-1 again. In late June 1941 the Germans scrapped the aircraft.

Enngines: 2 × Hispano-Suiza 14AB, 552 kW (740 hp) each

Propellers: 3-bladed

Wingspan: 14.40 m (47 ft 3 in)

Wing area: 33.80 sq.m (363.8 sq ft)

Height: 2.50 m (8 ft 2 in)

Length: 12.78 m (41 ft 11 in)

Empty weight: 2,600 kg (5,732 lb)

Gross weight: 5,094 kg (11,230 lb)

Max takeoff weight: 5,664 kg (12,487 lb)

Maximum speed: 450 km/h (280 mph; 243 kn)

Cruise speed: 320 km/h (199 mph; 173 kn)

Range: 1,000 km (621 mi; 540 nmi)

Service ceiling: 10,000 m (33,000 ft)

Rate of climb: 5.55 m/s (1,093 ft/min)

Guns: 2x 20 mm (0.787 in) Oerlikon cannon, and 4x 7.9 mm (0.311 in) machine guns

Bombload: 1,600 kg (3,500 lb) of bombs carried internally

Crew: 3-4

Inspired by the Heinkel He 119, Yokosuka began to design an aircraft of a similar layout, known as the Y-40, in 1943. Headed by Commander Shiro Otsuki, the aircraft project was a pressurized, two-seat, unarmed, high-speed, reconnaissance aircraft of all-metal construction that featured tricycle retractable gear. The Japanese Navy decided to take advantage of this work, and issued an 18-Shi specification built around the Y-40. The design was approved, and the Y-40 officially became known as the R2Y1 Keiun (Beautiful Cloud). The construction of two prototypes was ordered.

Commissioned for the Imperial Japanese Navy after the R1Y design was cancelled due to its disappointing performance estimates, the R2Y used coupled engines driving a single propeller and also featured a tricycle undercarriage. The Yokosuka R2Y Keiun (景雲 – “Cirrus Cloud”) was a prototype reconnaissance aircraft.

The Keiun was powered by two 60-degree, inverted V-12 Aichi Atsuta 30 series engines, licensed-built versions of the Daimler-Benz DB 601. The engines were coupled together by a common gear reduction in a similar fashion as the DB 606. The resulting 24-cylinder power unit was known as the Aichi [Ha-70]. With a 5.91 in (150 mm) bore and 6.30 in (160 mm) stroke, the engine displaced 4,141 cu in (67.8 L) and was installed behind the cockpit and above the wings. The Aichi [Ha-70] engine was to be turbocharged and rated at 3,400 hp (2,535 kW) for takeoff and 3,000 hp (2,237 kW) at 26,247 ft (8,000 m). Without the turbocharger, the engine was rated at 3,100 hp (2,312 kW) for takeoff and 3,060 hp (2,282 kW) at 9,843 ft (3,000 m). The engine drove a 12.47 ft (3.8 m), six-blade propeller via a 12.8 ft (3.9 m) long extension shaft that ran under the cockpit. Engine cooling was achieved by radiators under the fuselage and inlets for oil coolers in the wing roots. A ventral air scoop was located behind the engine to provide induction air for the turbocharger and air for the intercooler. Speculation suggests the first scoop on the side of the aircraft provided cooling air for the engine’s internal exhaust baffling, the second, larger scoop provided induction air for the normally aspirated Aichi [Ha-70] engine installed in the prototype, and the final two ports were for the engine’s exhaust.

The pilot sat under a raised bubble-style canopy that was toward the extreme front of the aircraft. The radio operator/navigator occupied an area in the fuselage just behind and a little below the pilot.

By the fall of 1944, the direction of the war had changed, and Japan no longer needed a high-speed reconnaissance aircraft. The R2Y1 Keiun was all but cancelled when the design team suggested the aircraft could easily be made into a fast attack bomber. In addition, the Aichi Ha-70 power plant would be discarded, and one 2,910 lb (1,320 kg) thrust Mitsubishi Ne 330 jet engine would be installed under each wing. A fuel tank would be installed in the space made available by the removal of the piston engine. The bomber version would carry a single 1,764lb bomb under the fuselage, and carry cannons in the nose. This jet-powered attack bomber had an estimated top speed of 495 mph (797 km/h). The Japanese Navy decided to accept the modified design. Yokosuka were given permission to produce one R2Y1 piston-engined prototype to test out the aerodynamics of the design, while also working on the jet-powered R2Y2 Keiun Kai. It did not enter construction before the end of the war.

The decision was made to finish the nearly completed R2Y1 airframe and use it as a flight demonstrator to assess the flying characteristics of the aircraft. With pressurization, the turbocharger, and the intercooler omitted, the R2Y1 prototype was completed in April 1945 and transferred to Kisarazu Air Field for tests. Ground tests revealed that the aircraft suffered from nose-wheel shimmy and engine overheating.

Adjustments were made to overcome the issues, and the Keiun took to the air on 29 May 1945 (date varies by source and is often cited as 8 May 1945), piloted by Lt. Commander Kitajima. The flight proved to be very short because the engine quickly overheated, and a fire broke out in the engine bay. Lt. Commander Kitajima quickly returned to the field, and the R2Y1 suffered surprisingly little damage.

On 31 May during a ground run to test revised cooling, the engine was mistakenly run at high power for too long and overheated. The engine was removed from the aircraft to repair the damage. The R2Y1 sat awaiting repair for some time before it was destroyed by Japanese Naval personnel to prevent its capture by American forces (some say it was destroyed in an Allied bombing raid).

Because of the end of the War, the second R2Y1 prototype was never completed nor was the design work for the R2Y2.

Three were built, but only one was completed.

R2Y1

Engine: 2 x Aichi-10 Ha-70, 2550kW (3,400 hp / 3,100hp at 9,845ft)

Propeller: 6-bladed constant-speed metal

Wingspan: 14.0 m / 45 ft 11 in

Length: 13.05 m / 43 ft 10 in

Height: 4.24 m / 13 ft 11 in

Wing area: 34.0 sq.m / 365.97 sq ft

Max take-off weight: 8100-9400 kg / 17858 – 20724 lb

Empty weight: 6015 kg / 13261 lb

Fuel capacity: 1,555 l (411 US gal; 342 imp gal)

Max. speed: 715 km/h / 444 mph at 10,000 m (32,808 ft)

Cruise speed: 460 km/h / 286 mph at 4,000 m (13,123 ft)

Landing speed: 166 km/h (103 mph; 90 kn)

Ferry range: 3,611 km (2,244 mi, 1,950 nmi)

Service ceiling: 11,700 m (38,400 ft)

Time to altitude: 10,000 m (32,808 ft) in 21 minutes

Crew: 2

R2Y2

Engine: Two Ne-330 axial-flow turbojets

Power: 2,910lb thrust each

Crew: 2 (pilot and radio operator/ navigator)Span:

Armament: Forward firing cannon

Bomb load: One 1,764lb bomb