The Hjordis, named after the heroine of a Norse saga, was designed by Sqn Ldr Mungo Buxton of the Royal Air

Force. Buxton, in partnership with Philip Wills, placed the order for its construction with Slingsby in 1934, but for some reason it never acquired a Slingsby type number. The drawings supplied by Buxton showed all the main features of the proposed aircraft, but most of the details remained to be worked out. A good deal was evidently done in the workshops and never fully committed to paper. Only one of the type was built.

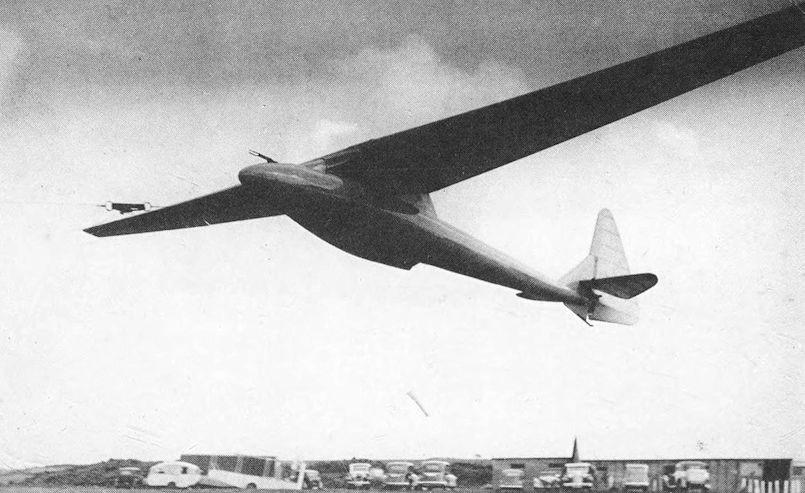

The Hjordis had a cantilever wing of unusually high aspect ratio, strongly cambered and very thick at the root, mounted on a very tall, narrow pylon above the fuselage. Spanning just over 15.5m (51ft) the wing had a slight anhedral angle. Viewed from the front, the undersurface of the wing was flat from tip to tip. The taper in thickness resulted in the upper side of the wing descending. This unusual feature was never explained by Buxton, but he may have thought it would improve response to the lateral controls. There was a small

wheel on the control column instead of the familiar stick to operate the ailerons, as there was insufficient room to move a joystick laterally.

Buxton had in mind the needs of private-owner syndicates who would operate with minimal crew. He aimed to achieve the best possible soaring performance with a relatively modest wing span. A tapered planform was necessary, both to cut tip vortex drag and to ensure adequate depth of spar to accommodate bending loads at the inner end of the cantilever wing. The taper of the Hjordis wing was fairly pronounced, the ratio being about 4:1.

On the Rhonadler, large amounts of negative wing twist or ‘washout’ were used to ensure that the tips did not stall early. Hjordis incorporated similar ideas.

The choice of the thick, strongly cambered Gottingen 652 section for the wing root of Hjordis was influenced by the successes of the famous Fafnir sailplane designed by Alexander Lippisch, The section at the mid semi-span position was one Buxton s own devising, thinner and less strongly cambered than Go 652. From this position the profile changed gradually to RAF.32 at the extreme tips. The layout was cleverly devised so that, geometrically,

the base lines from which the various profiles were plotted remained in alignment, Buxton pointed out that the wing could be built on a flat bench. Each rib would touch the flat surface at two points and would automatically be at the required rigging angle, no complicated blocking up or jigging being needed. Because of the gradual variation of camber and thickness there was 6° of aerodynamic washout, although geometrically there appeared to be none. This stratagem was entirely successful, and tip stalling was never a problem with Hjordis. It was found impossible to make the sailplane spin.

The main wing spar was necessarily massive, the flanges laminated in spruce with plywood shear webbing and hefty steel fittings with horizontal pins to attach the wings separately to the fuselage pylon. A lighter rear spar carried the ailerons. The ribs, with narrow spruce booms and substantial plywood webs to stiffen them, were spaced at a pitch of 8in (203mm). This was less than usual, but obviated the need for intermediate sub-ribs ahead of the main spar. The most unusual feature of the wing was that it was covered with plywood back to the auxiliary spar, when the usual practice at this time was to use ply skin only around the leading edge and cover the rest with doped fabric. The advantages of the extended stressed skin were that the aerofoil section was more accurately preserved and the wing was very much stiffer in torsion.

The total weight of the aircraft was considerably increased, and unlike most sailplanes of the period the plywood covered areas were painted, which added a few more pounds. The colour was light grey, or turquoise grey according to some accounts, rather than white.

The fabric covered areas were clear doped and varnished, which was orthodox practice. After assembly, the gap between the wings was closed with a light plywood fairing. The fuselage was a nearly perfect cigar shape with only slight downward droop of the form near the nose. The usual semi-monocoque structure was employed, with four main longerons supported by circular crossframes and a complete plywood skin. The tall pylon was based on two very robust vertical spars connecting the wing fittings directly to the main skid attachments.

Buxton had seen various types of accidents to sailplanes with pylon-mounted wings. In some cases, when a tip dragged on the ground during a landing, the wing could twist completely off the fuselage. In a touchdown with a little sideways drift, the fuselage might be torn off and rolled under the wing. Minor errors of judgement could thus become bad accidents. The Hjordis pylon was stressed to withstand a side load of half a tonne applied at the skid, and 50kg (110lb) dragging force applied at the wingtip. The tailplane was of the all-moving type, mounted part way up the triangular fin. Hjordis had a large rudder with only a little aerodynamic balancing.

After the end of the 1935 BGA meeting, the editor of Sailplane and Glider reported that the new sailplane ‘seems to have a simply phenomenal performance’. Wills carried off the de Havilland Cup for height gain and the Manio Cup for a pre-declared out and return cross country flight of 38km (23.5 miles).

The wing itself, though torsionally stiff, was too flexiblein bending near the tips. After landing, a sailplane tilts over until the wingtip on one side touches the ground. The flexibility of the outer spars allowed the underside to be pressed down on to the surface for some distance, so any stones readily punctured the thin skin. Re- skinning with heavier plywood was necessary. Philip Wills wrote: ‘Quite soon it became apparent that designers have paid too much attention to aerodynamic form and far too little to the shape of the human behind and the needs of the human frame’. He was giving an account of the flight he made in July 1936, which, unpleasant though it was for him, broke the British distance record, 167km (103.5 miles) from Dunstable to the coast south of Lowest oft. The sun beating into the cockpit through the minute talc roof soon gave me a splitting headache. Constant circling and hard work rapidly transformed this into a sick headache. Then came a thirst like the Sahara, closely followed by cramp.’ Relief came only when he ‘burst thickly out of Hjordis’ and sensed ‘the fresh, cool smell of the sea.’ Additional vents were cut. The cramps were reduced a little by chopping out half-moon shaped pieces on either side of the canopy. From this time Wills flew Hjordis with his shoulders sticking out into the breeze.

Buxton himself admitted that the controls were not good. The elevator was too sensitive, and without a trim tab at high speeds the load on the stick was too great. The ailerons were also unsatisfactory. They lacked diagonal stiffeners and so deflected several degrees at the ends under load, giving poor control. The fin was too small. More directional stability was needed.

Probably most serious of all, the Hjordis had no spoilers or airbrakes. Philip Wills was beginning at this time, as he put it, to nibble nervously at clouds, and he had fitted some gyro instruments. On his first serious attempt to circle up blind inside a cumulus, at an Easter meeting in Derbyshire, he lost control within a minute or two. The airspeed indicator went twice round the dial and he ‘burst out of the cloud base in a dive rather over the vertical’ with the Hjordis ‘bellowing like a bull in considerable pain’. The sailplane did not break up, probably owing to the good torsional resistance of the plywood skinned wings.

It had originally been intended to fit an airbrake. The idea was to make the rudder in two pieces, split like a clamshell along the hinge line. When right or left rudder was applied in the normal way, the two clamshells would move together to the same side. To brake, both of the pilot’s feet would be pushed forward and the two shell halves would open out in opposite senses to create high drag. This rudder brake was never fitted. Buxton wrote that among so many new developments this seemed just one too much.

Apart from the dangers of cloud flying without airbrakes, it was a pity that the Hjordis was without even elementary spoilers for landing. Wills damaged it many times because there was no reliable way of getting safely down within a reasonable space. Sideslipping, turning the entire fuselage at an angle to the airflow, could help during the early phases of a landing approach, but the wings had to be levelled well before touchdown. Skimming a few feet off the ground, some extra drag could be created by fishtailing; using the rudder to yaw the aircraft from side to side. This also had to stop before landing. On levelling out and straightening up to flare-out, just when high drag was needed, it was reduced because of the proximity of the ground and its restraining effects on the induced down wash. After a cross-country flight Hjordis would float and float and float across a small field until it hit the upwind boundary or until the pilot deliberately ground-looped to prevent hitting it. In one landing Wills turned it over completely. Buxton mentioned another accident which broke one wing in two and severely twisted the pylon. Only his strong vertical members prevented the glider wringing its neck. There were many other occasions when it had to go back to Slingsby for repairs.

Despite the limitations of his aircraft, Wills had many successes. He captured national records for height gain as well as distance. In the 1936 BGA competitions at Camphill in the Peak District he won the cross-country flying prize, reaching Lincoln. It was not customary at this time to total up the scores and declare a National Champion. Separate prizes were awarded for slope soaring duration flights and gains of height as readily as for distance. It was recognised, nonetheless, that Wills and Hjordis were an outstandingly good combination.

The first truly international soaring championships were held in Germany during July 1937. Five British sailplanes were entered. Wills preferred to take Hjordis, with which by now he was thoroughly familiar, rather than one of the new and, as it proved, unreliable King Kites. Wills placed 14th, exactly halfway down the list. He had his usual problems on landing, ending one flight with the sailplane’s nose in a stream but he and the rest of the British group learned a great deal by observing how the more experienced German and Polish pilots flew. Doubts about the thermal soaring capabilities of their large aircraft were entirely dispersed.

Advertisements appearing in Sailplane and Glider early in 1938 stated:

For sale, HJORDIS, the outstanding British high efficiency sailplane. It holds the British distance and goal flight record, placed first in the 1937 British competitions; holds most of the British Gliding trophies and awards. It has done over 850 miles of cross-country flying (on purpose), has been dived to 125mph in cloud (by accident), is extremely strong (by gum); won the distance trophy (by Wakefield); is in first class condition (by Slingsby); and is for sale by Philip Wills.

It was bought eventually by Messrs Brink & Horrell in Johannesburg. Very little was heard about its exploits after it left Britain, but it was flown in South Africa for some years. A rare photograph shows that, to begin with at least, it retained its British civil registration letters, G-GAAA, and the 1937 Wasserkuppe competition number 15 remained on the nose. Officially it was registered as ZS-23. It was used late in 1939 by E. Dommisse for a record height climb to 3,600m (12,000ft) above ground, which, since the take-off was from Quaggaport 1,740m (5,800ft) above sea level, represented an altitude of 5,340m (17,800ft) without oxygen breathing apparatus. The last 1,200m (4,000ft) of the ascent were in cloud without blind flying instruments, Dommisse relying on his airspeed indicator and a simple cross-level bubble.

What finally became of Hjordis is not known.

Slingsby Hjordis

Wingspan: 15.54 m (51 ft 0 in)

Wing area: 11.52 m2 (124.0 sq ft)

Aspect ratio: 21

Airfoil: Göttingen 652 at root, RAF 32 at tip

Length: 6.58 m (21 ft 7 in)

Empty weight: 144 kg (317 lb)

Gross weight: 218 kg (481 lb)

Rate of sink: 0.61 m/s (120 ft/min) minimum

Lift-to-drag: 24

Wing loading: 18.9 kg/m2 (3.9 lb/sq ft)

Crew: 1