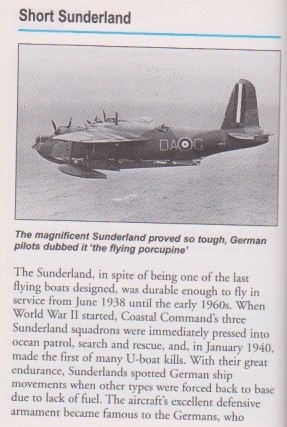

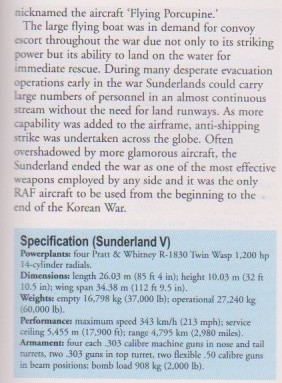

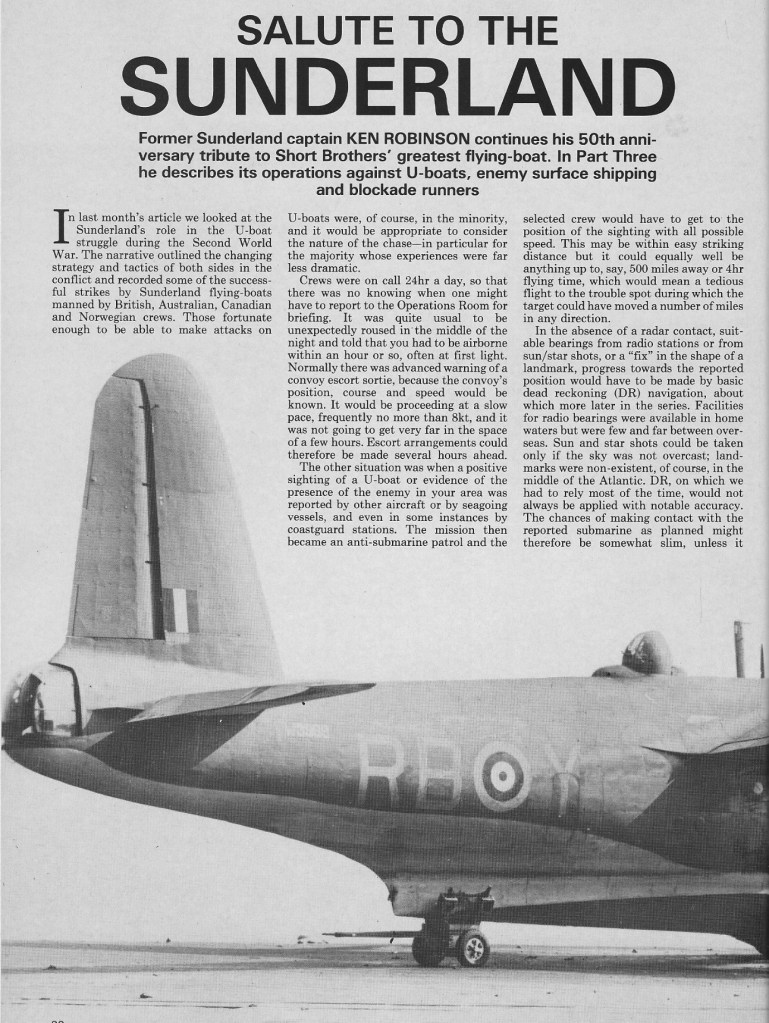

Back to Short Sunderland

The amazing adventures of Sunderland flying boat T9114

In 1943, a number of ’flying boat’ seaplanes and other vessels found one thing going wrong after another. But in the end, aviation history was made in West Wales

If you lived in Pembroke Dock during the 1940s you would have heard the thunderous roar of the Sunderland flying boat overhead. RAF Pembroke Dock was on the south side of the Milford Haven Waterway, opposite the town. By 1943, 99 flying boats rested on water or land there. From the quayside you could see their rows stretching across the water, moored to buoys.

The station’s motto, ‘Gwylio’r gorllewin o’r awyr’, means ‘To watch the west from the air’. Its seaplanes played a vital part in winning the Battle of the Atlantic, undertaking multiple roles including reconnaissance, tracking enemy shipping, Air Sea Rescue (ASR), Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW), and convoy escort. If Britain had lost that battle the outcome of the second world war might well have been radically different.

There was constant activity at the base during the war. On 28 May 1943, Sunderland flying boat JM675 (UT-O) from 461 Squadron took off on an operational patrol to rescue the crew of a downed Armstrong Whitworth Whitley bomber. Its survivors were eventually spotted in a dinghy and the flying boat radioed for permission to land.

The aircraft descended and bounced off three swells on touchdown, before stalling and diving vertically into the next swell. Its bow was torn off up to the cockpit, killing Flight Lieutenant WSE Dods and leaving the First Pilot badly injured. The survivors climbed into their own dinghy and joined those of the downed Whitley, lashing the two dinghies together and waiting for help.

Early the next day another Sunderland (T9114) from the same squadron, flown by pilot PO Singleton and his crew, took off on a normal anti-submarine operation. They were soon diverted and told to look for any survivors of the two downed aircraft. The crew of 11 included an engineer, a bombardier, a navigator, a wireless operator, two pilots, and five aerial gunners.

Crew members were capable of undertaking more than one role, with duties organised in shifts. The wireless operators, for instance, did an hour in the mid-upper turret, an hour as wireless operator, and half an hour on radar, because of the stupor and eye-strain that could be suffered after a short time.

A solitary aircraft might patrol up to 12 or 13 hours – 500 miles in the Atlantic – but was well-equipped for it. Compared with other aircraft, the Sunderland boasted comfortable features including upper and lower decks, a wardroom, two bunks, and a flushing toilet, washbasin, and mirror. Also, essentially, a galley where drinks and hot food like corned beef rissoles or spam fritters could be served.

Just after 6:30am, Sunderland T9114 spotted the survivors and dropped smoke floats and green dye to determine wind and sea conditions. The sea was considered borderline, but nevertheless they landed 175 nautical miles southwest of Bishop Rock. The plane was overloaded and takeoff proved impossible, with 16 survivors, 11 crewmen, eight depth charges, and 1500 gallons of fuel aboard.

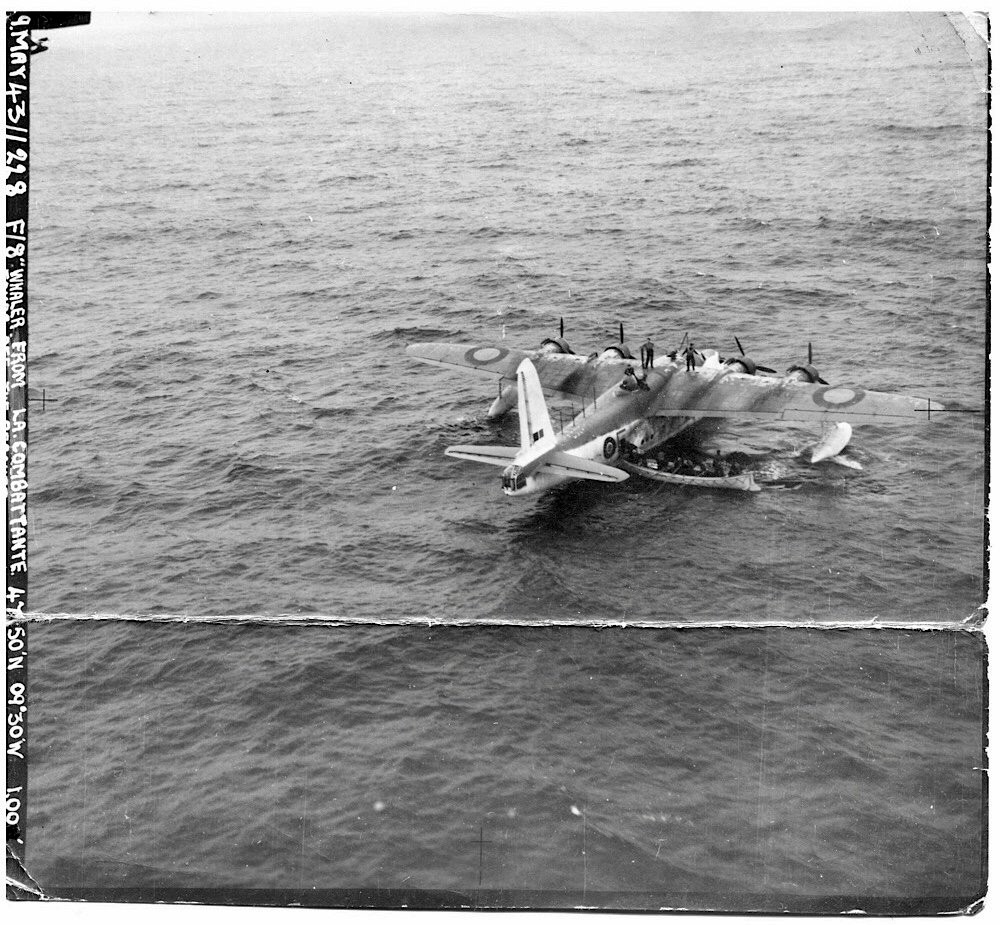

While rescue operations were taking place, another Sunderland and a Wellington circled overhead. Singleton asked them to locate a Royal Navy ship known to be in the area – La Combattante, a Free French destroyer. It rescued all the Whitley survivors and five of the T9114 crew.

Sunderland T9114 was then taken under tow and they headed back to the UK. During the four-hour trip the aircraft narrowly missed a floating mine and the tow line parted twice, the mooring post finally snapping and casting the Sunderland adrift.

Fortunately, the swell had moderated, giving Singleton and his crew an opportunity to take off. To lighten the load further, the destroyer sent an armourer to disarm the eight depth charges aboard, which were then jettisoned. T9114 turned into the wind and Singleton hauled back the controls to reach maximum take off speed. But just as the plane lifted it was hit by a particularly large wave, which smashed into the hull.

A crew member was sent below to inspect the damage. He informed Singleton that a seven-feet-wide hole had opened below the waterline. This made any sea landing impossible and, with no parachutes aboard, only one deadly option existed. The Sunderland was a flying boat, not an amphibious craft. It was designed to land on water and had no undercarriage, wheels, or brakes.

Singleton chose RAF Angle, not far from Pembroke Dock, for a crash landing. The aircraft signalled those intentions to base. As they approached the coastline, the skeleton crew threw out heavy items, excess equipment, and anything flammable on board. They adopted crash positions as RAF Angle came into sight.

Planting a 27-tonne flying boat on land had never been tried before. Singleton lined the plane up as he glided over the aerodrome boundary and brought T9114 down onto the grass, parallel with the runway. The hull cut an enormous furrow in the earth. The Sunderland tilted on its port side as the port float was torn off, causing it to skew around in a partial arc before coming to a halt.

Half of 461 Squadron had turned out to see the landing. The whole episode was captured by the Commanding Officer through his cine-camera in a chasing car.

The motley crew, much of their dry flying gear having been given to the other survivors, exited unscratched through the astrodome. They slid or scampered down the tilted wing to a warm reception below, leaving the engines still running before some climbed back in to turn them off.

Rather than moving a safe distance from the aircraft, some crew lit cigarettes, oblivious to fire risk and perhaps not realising the magnitude of what had just happened – the significance to aviation history of the first-ever landing by a flying boat on soil. The feat has never been repeated. The only-ever such landing.

The Free French destroyer delivered all passengers to safety, including the injured Sunderland JM675 pilot. All able personnel returned to duty, but Sunderland T9114 never flew again. The removed forward section of the nose was used at RAF St Athan as a synthetic trainer for flight engineers.

Sunderland T9114 crew: F/O George Singleton, Pilot (Captain). P/O Howe, 2nd Pilot. F/Sgt Taplin, Engineer. F/Sgt Hules, Bombardier. F/O Harry Winstanley DFC, Navigator. Sgt H Hall, Wireless Operator. Sgt Hammond, Aerial Gunner. F/Sgt Ronald Church, Aerial Gunner. F/Sgt John ‘Johnny’ Lewis, Aerial Gunner. F/Sgt Stevens, Aerial Gunner. P/O George Viner, Aerial Gunner.

Gordon Singleton of St Kilda, Australia married a local girl and settled in Britain. He was a great supporter of the Pembroke Dock Heritage Centre, the only museum focusing largely on the RAF Flying Boat Service. When he died aged 97 in 2013, his ashes were scattered on the airfield where he made aviation history.

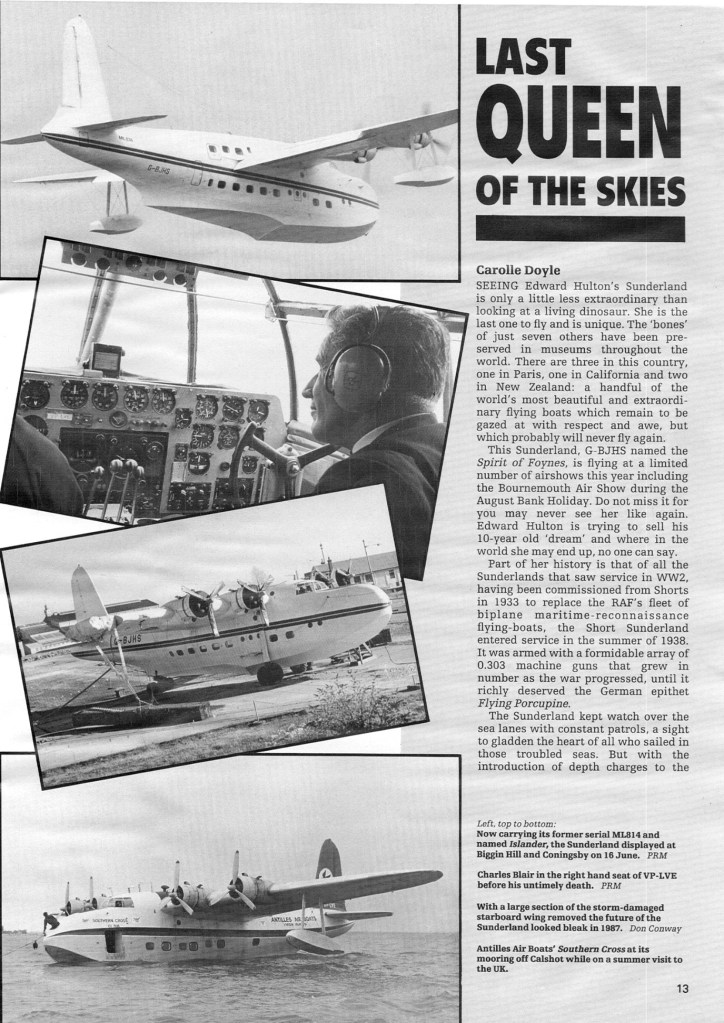

The Short Sunderland continued with a great safety record, remaining in service for the RAF Far East Air Force at Singapore until 1959 and the Royal New Zealand Air Force No. 5 Squadron until 1967. It’s an amazing testimony to longevity for any aircraft, especially one that first entered service in 1938.

The last RAF Pembroke Dock flying boat squadrons were disbanded in 1957, and the base closed in 1959. But it would take part in one last operation, code-named Magic Roundabout, in 1979. In its eastern hangar was built another flying boat, a full-scale Millennium Falcon, for the Star Wars film The Empire Strikes Back.