Himself an aeronautical engineer, Jewett designed, and the Quickie Aircraft shop staff started building, an airplane called Big Bird in which Jewett intended to break the absolute distance record for un-refueled airplanes, set in 1962 at 12,519 miles by a B-52. Burt Rutan thought ill of the design, and after he fell out with Jewett and Sheehan, the principals of Quickie Aircraft and RAF repeatedly sniped at each other in unseemly ways on the ramp at Mojave and in the aviation press.

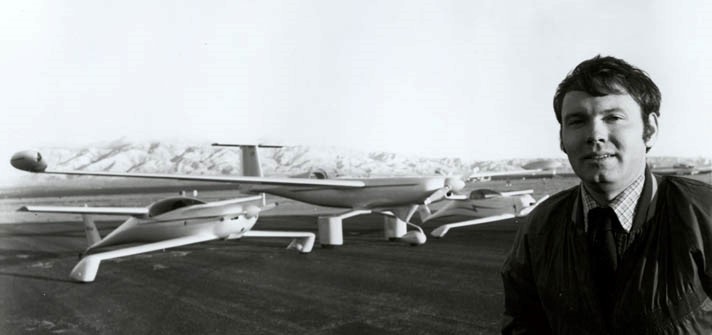

After a hostile encounter on the airport camp with Jewett and Sheehan, Dick Rutan proposed to Burt that they do Jewett one better and build an airplane that could fly un-refuelled all the way around the world. The Rutan brothers soon made a public announcement of their goal, reducing Big Bird to insignificance even before it had flown. Stung, Jewett quickly announced the same goal for Big Bird — which he rechristened Free Enterprise [N82X] — though his airplane was not really equal to the task. Mike Huffman was brought to Mojave by Quickie to help finish the design and construction. His contributions included the unique landing gear dolly, which was designed to be jettisoned after the airplane took off on its record-attempting flight. At the completion of the flight, the airplane was to be landed on a wooden skid on the bottom of the aircraft.

Big Bird was an updated version of the concept used by Jim Bede’s BD-2 Love One, also designed for a global flight: both aircraft use modified sailplane wings, but Big Bird is rather smaller and less powerful than the BD-2.

Quickie’s aircraft was based on the bonded-aluminium wings of a Laister Nugget sailplane, modified with tip and integral fuel tanks and mated to a new glassfibre/foam fuselage and T-tail.

Powered by a Polish-built Pezetel-Franklin 135 horsepower PZL-F 4A-235 four-cylinder engine, but designed to carry only one person – the pilot – the plane featured a full autopilot system, a specially developed S-Tec AFCS with a three-axis alarm system to warn of excursions from track, with alarms that enabled the pilot to sleep for short periods, while being supplied oxygen from a cryogenic liquid oxygen, rather than the typical gaseous oxygen. Jewett planned to carry 10 gallons of drinking water and follow a low-residue diet similar to that used by astronauts.

The “Big Bird” carried 350 gallons of fuel, and the planned world flight was slated to both begin & end in Houston, Texas. A lightweight Litton Omega/VLF navigation system and lightweight weather warning equipment were also installed, helping the plane cruise at 24,000 feet at 175 knots.

On July 2nd, 1982, Tom Jewett took “Big Bird” on a test flight. But immediately after takeoff, Jewett radioed the chase plane that he had some minor problem & was going to land. After turning final, about 200 feet above the ground, he reported “Something broke, I’m going in…” and the aircraft crashed at a slight nose down attitude a half mile short of the end of the runway.

The NTSB investigation found that the continuity of flight control was established & no evidence of preimpact flight control was evident. Unfortunately, there were no drawings or design data available for the aircraft, and its fuselage & empennage had not been static tested.

The investigators also concluded that a break at the rear of the cockpit appeared to be in an area of poor design and the composite structure behind the cockpit rails looked questionable in its cross-sectional area to handle the bending loads in this area. The NTSB determined that an in-flight separation of the fuselage at the rear of the cockpit by as much as a single inch could have placed the stabilizer in a three-degree nose up pitch angle rendering the elevator insufficient to hold the nose up.