The Northern Aeroplane Workshops F.1 Camel The project was started around 2001, after the construction of the Sopwith Triplane and Bristol M.1C.

Eric Barraclough was the mainstay and inspiration behind the NAW. Having worked for Comper, Heston Aircraft and Auster, he was steeped in aviation. “When the Bristol M1C was coming to completion, we were looking at another project”, recalls Robert Richardson, another NAW lynchpin. “Eric had the idea of building the first Blackburn aircraft, which was an abomination, it really was. None of us were interested in it at all. Then he suddenly turned round and said, ‘I’ve got some Camel drawings in my loft’. He seemed to have forgotten about them.

The first metal was cut when they were still on with the Bristol, in December 1995. That was at the Mirfield workshop, at Butt End Mills, but shortly after that they moved to the workshop at the Skopos Motor Museum in Batley. Once the Bristol was delivered, they started full-time on the Camel.

Eric Barraclough died in November 1997, but the standards he had always desired in NAW’s projects set the tone. Adherence to the original remained to the fore.

They built the fuselage sides first. All the sub-assemblies like the wings and fuselage were done in jigs.

Most of the airframe is spruce, but the longerons are ash. They had woodworkers Chris Lawson, who had his own woodworking company in Skipton. They ordered the streamlined wires from Bruntons, who were making these wires during the First World War.

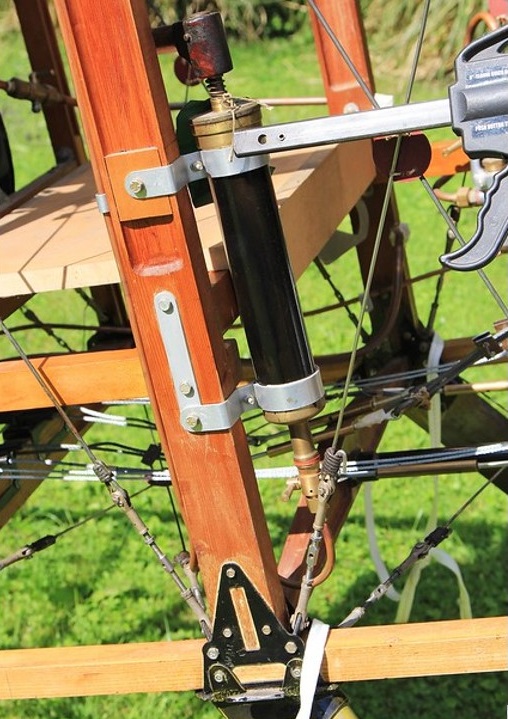

Tube left over from the Triplane for the undercarriage was utilised. It had been specially drawn by a firm called T. I. Reynolds in Sheffield. There were parts coming from all over the place, apart from what they were making in the workshops. The cockpit instruments were sourced by Shuttleworth.

Of the metal fittings made in-house, CAD [computer-aided design] was available, but no one had the expertise to use it, or CNC [computer numerical control] machines and so on. So, it was done the old way. Sopwith would have stamped these fittings out, but they drew them out on a piece of metal, cut them out with a saw, filed them up and bent them as appropriate.

The engine was Shuttleworth’s. All they had was a crankshaft, which was used to set various things up. When they first approached Shuttleworth about the Camel project, one of the things that came to the fore very quickly was a suitable engine. The then chief engineer, Chris Morris, had another Clerget — it’s turned out to be a 9Bf 140hp long-stroke. They thought they could get that airworthy, which they’ve been able to do. It took a lot of work; it needed new pistons, new cylinders, and parts of the tappets as well. Shuttleworth engine specialist Phil Norris is an absolute wizard on rotaries.

The first two NAW aircraft were done under CAA auspices, but the Camel was done under the LAA [Light Aircraft Association]. That worked out very well. One of the pilots down at Shuttleworth, Rob Millinship, was the LAA inspector.

Having proved ideal for so long, conditions in the Batley premises deteriorated when they were sold off. Then in 2013 the lease was due for renewal, and Shuttleworth weren’t prepared to renew it. About six NAW members were working on the Camel when it left in August 2013.

At that point, the undercarriage needed final welding. The cables were in, but they weren’t spliced. The systems weren’t in, like the air, fuel and oil systems, so that was all done at Old Warden. That’s probably a good thing, because they’ve got to maintain it. They’ve had to put a small access panel on the port side, which isn’t authentic, but they weren’t able to get to the fuel filter, even going upside-down in the cockpit.

The big things as far as modern standards were concerned were that a four-point harness was put in for the pilot, rather than a lap strap, and obviously the glue. The old casein glue or pot glue that they used in the First World War is not a good idea, so they used Aerodux 500, a very good modern glue.

Now overseen by the Shuttleworth chief engineer Jean-Michel Munn, at Old Warden the Camel made visible progress towards completion. The plywood cockpit and side panels, which proved troublesome, were completed before the airframe was taken down to be covered, using synthetic materials rather than linen. The chosen colour scheme was that of a Ruston Proctor-built example operated by No 70 Squadron, Royal Flying Corps, the first front-line unit to receive the type. It carries the serial D1851 and is named Ikanopit (‘I can hop it’).

Engine runs began in August 2016, leading up to the following May’s successful maiden flight.

When ‘Dodge’ Bailey, the Shuttleworth Collection’s chief pilot, took Sopwith F1 Camel reproduction ‘D1851’/ G BZSC into the air for the first time at Old Warden on 18 May 2017, it brought one of the historic aviation scene’s most compelling stories to a close. The West Yorkshire-based Northern Aeroplane Workshops, established back in 1973, shut up shop when the Camel was moved to Old Warden for completion during the summer of 2013, but the machine’s maiden flight marked the very end of the group’s final project.

In preparation for that, ‘Dodge’ Bailey did a great amount of homework. He used three-view diagrams of different Sopwith types, all to the same scale, on acetate sheets that could be laid over one another to afford the most direct comparison: they depict the Camel, 1½ Strutter, Pup, Triplane and Snipe. Amongst other things, they showed that the Camel’s tailplane is about 60 per cent of the size of the Pup’s, and that the fin is smaller too. The tail arm is longer on the Triplane, making the tail more effective. They both preceded the Camel; its Snipe successor, meanwhile, saw the tail going back to the sizes of the previous aeroplanes, and the fin and rudder made significantly larger. “That tells you a lot about what the aeroplane’s probably going to be like”, says ‘Dodge’. “A very simple technique, but quite illuminating.”

Then there were period scientific and technical papers to read, drawings made by the Germans of a captured Camel and reproduced in Flugsport to examine, and numerous references to study. In his weighty tome Flying Qualities and Flight-Testing of the Aeroplane, former CAA test pilot Darrol Stinton described flighttesting a Clerget-engined Camel. A May 1968 issue of Flight International includes a piece by six-victory Royal Naval Air Service pilot Capt Ronald Sykes on flying a Bentley BR1-powered example. Best of all, ‘Dodge’ feels, are the writings of Wg Cdr Norman Macmillan, who was operational on RFC/RAF Camels on the Western Front and in Italy, and subsequently flew the type while instructing at a fighter school back home in the UK. Apart from several books, Macmillan wrote an article on his Camel experiences that, some years after his death, appeared in the October 1984 Aeroplane Monthly; it was called ‘A Fierce Little Beast’.

In that feature, says ‘Dodge’, “There’s some really good advice, and counterintuitive advice: for example, to start the take-off with the stick on the carburettor intake tubes. Because the Camel cockpit is set more forward, the carburettor is closer to the pilot than in earlier types. To start the takeoff with the stick on the intake tubes means the stick is fully forward. It’s pretty unusual to do that. On most taildraggers you would start with the stick back, and some you would start with the stick kind of neutral. What I had to think when I read that was, ‘why on earth is he telling ab initio students to do that?’

“This is one of the bits that I don’t understand about the thinking at Sopwith at the time. If we overlay the Camel and the Pup in side view, you can see that the cockpit has moved from the trailing edge to under the centre-section, so the distance from

the cockpit to the engine has changed; they moved the pilot forward. In the Pup, the area under the guns, pretty much where the centre of gravity is, is where the fuel tank is. Any aircraft designer will tell you to put the fuel tank on the centre of gravity; then, as the fuel burns, it doesn’t change the CG. Whatever made them move the cockpit forward means that the fuel tank can no longer go there so it goes behind the cockpit, well aft of the CG. When the fuel tank is full of fuel, the CG is a long way aft. That’s a clue to why the guy is saying, ‘stick fully forward’. It means that when the aeroplane is in flight it is not in trim.

It was one of its Camels, B7270, that was officially credited with the shooting-down of Manfred von Richthofen before evidence came to light that the ‘Red Baron’ probably fell victim to ground fire. Clayton & Shuttleworth employees were given a speciallyprinted leaflet commemorating their product’s feat.

“Now, you have to be a bit careful about the term ‘in trim’ because it means different things to different people. To pilots, ‘in trim’ means, ‘I have trimmed the aeroplane; I can take my hands off and it flies straight, it doesn’t pitch up or pitch down’. That is, if you like, ‘controls-free in-trim’… To a flight dynamicist, ‘in-trim’ means that the sum of the moments is zero; in other words, that the aeroplane isn’t pitching, but the pilot might be holding a huge control deflection and/or force to hold it in that condition. If he lets go of the stick it wouldn’t be in trim at all; it would pitch. The Camel is like that. In order to stop the aeroplane pitching you need a relatively large stick force. What the aeroplane wants to do when you’re taking off with a full fuel tank is pitch up.

“Imagine that a student used to taking off in an aeroplane with the stick back takes off in a Camel — it’s got twice as much power, maybe three times as much, as he’s used to. It’s very lightly wing-loaded and it’ll be airborne in no time. If the stick is back and the aeroplane is ‘out of trim’ it will just pitch up as it leaves the ground, and he will just stall and crash straight away.

“By putting the stick forward Macmillan knows there is no chance of the pilot putting the aeroplane on its nose, because the CG is so far aft. The first thing that happens is that he’ll see the tail coming up once the take-off starts, and then he can adjust the stick position. If he’s late, if he holds the stick back and doesn’t get it forward early enough, the aeroplane’s going to pitch up. It’s all about anticipating the reaction of the aeroplane when it gets airborne. You don’t actually leave the ground with the stick fully forward; like I say, as soon as the aeroplane’s rolling and the tail comes up you can move the stick to hold the normal take-off attitude for a taildragger. When you get airborne you’re pushing on the stick all the time to stop the aeroplane pitching up.

“I am told that if you run the aeroplane right out of fuel, like they would have done, by the time it’s empty the CG has moved pretty much on to the forward limit, and now you’re pulling all the time to the point where it became quite difficult to do three-point landings. The pull force needed to get to that position was quite a lot, and you might run out of elevator before achieving the three-point attitude. We never fly it that short of fuel, so we’ve not been there.

“So, the Camel is, if you like, ‘out of trim’ with any sort of fuel in it at all, and under that ‘out-of-trim-ness’ it is also unstable. You’re dealing with an aeroplane that requires a force to maintain its attitude, but the force changes after a disturbance will likely be unpredictable.

“One of the mitigations we came up with was to only use a half-tank of fuel… the other thing was that, because [this Clerget] is a really nice engine, to throttle up relatively steadily. That made the take-off a little bit more manageable. I really anticipated the aeroplane to be unpleasant in pitch, because every bit of evidence suggested it would be, and it didn’t disappoint in that regard.

“I also expected turns, particularly to the right, to be compromised by the gyroscopic precession. I found on first acquaintance that even left turns were pretty unusual. These were climbing turns, because I was climbing out. I continued to climb until 3,000ft or so and then throttled back, and as soon as the power came back below about 1,000rpm the aeroplane started to get a bit more pleasant — or less unpleasant. The pitch deficiency is at its worst at high power, and pretty much has gone away by the time you’re gliding, so you don’t really notice it when you’re coming in to land. One of the things you tuck away in your head is, ‘if it all gets too much, throttle back’, which might be counter-intuitive to some people.

“What was more of a surprise was how directionally sensitive the aeroplane was. There are very few aeroplanes that I have flown that behave like this; I think the Comper Swift is similar, but not as bad. Most aeroplanes you want to fly in balance, so you put the slip indicator in the centre — using the rudder, normally. Once you have put the rudder in that place, and your feet hold the rudder in that place, things won’t change unless you change the power or the speed or aileron. That’s not the case in the Camel. Having put the aeroplane in balance it doesn’t stay that way. It’s the directional equivalent of the pitch handling characteristics, in the sense that it will diverge from that condition you thought you had sorted out, and you have to put it right again. Darrol Stinton refers to that as, ‘there is no stability, it’s all control’. You not only have to control the pitch, which you were kind of expecting, but the yaw as well…

”I expected turns, particularly to the right, to be compromised by the gyroscopic precession. I found on first acquaintance that even left turns were pretty unusual”

“What it boils down to is that you have to be actively in the control loop all the time. Reputedly the only time a Camel will fly hands-off in-trim is when it’s inverted. I think if you were to fly it enough you would get to love it, and in one of Macmillan’s books he reckons it’s maybe 15 hours on the Camel and then you’ve adapted to the aeroplane. I haven’t got 15 hours on the Camel; I’ve probably got three, so what I’ve been relating are first impressions of a strange aeroplane.”

In combat, flown by someone with the requisite experience, ‘Dodge’ says the Camel, “could be manoeuvred in a very unpredictable way, so it would be a very difficult target. Equally, they could get on the tail of a more predictable aeroplane, which couldn’t manoeuvre anywhere near as aggressively as the Camel. What the Camel couldn’t do was go fast; it couldn’t run away or chase, it just had to fight, and it did that very well in a tight dogfight.

“One of the things you notice when you’re flying tight turns is that the gyroscopics of the engine start to dominate things. If the aeroplane pitches up, the gyroscopic precession causes it to yaw to the right. Whenever you’re turning steeply, as far as the aeroplane is concerned it is pitching up to go round the turn. If you’re making a left turn, the aeroplane is pitching up so it’ll yaw right. To stop it yawing right you need to apply left rudder. When you enter the turn you use some left rudder and left stick; then, having got the bank on, the nose is pitching up and so that left rudder needs to stay on — and even a bit more. In a left turn it does not feel particularly odd. Now, in a right turn, you might need a little bit of right rudder as you start to roll in to balance, but as soon as a pitch rate appears that right rudder is no longer appropriate. You need left rudder now. In a steep right turn, if you don’t apply left rudder the nose will yaw down towards the ground. The tightness of the right turn is limited by how much left rudder you can get on. You can end up in a tight right turn, going round apparently on a sixpence, probably only just getting rid of the push force — so you’re not pulling particularly, you’re just relaxing the push force — with nearly full left rudder on, and the aeroplane is perfectly in balance. That does feel odd”. On other Sopwiths, he continues, “the gyroscopics are there, but they are less intrusive because the tail volumes are greater.”

Power is, of course, a factor. “This Camel has the 140hp, long-stroke Clerget engine. Somewhere in the documentation for that engine it says you must not use full throttle at sea level. Effectively it gives you a bit of enhanced performance at altitude that you’re not allowed to use low down. Full rpm would be 1,200- 1,250, and at that setting, with nearly full power on, the aeroplane is at its most cantankerous. But for what we need to do, we don’t ever need to apply that amount of power. What I’ve found is that if we take off with maybe 1,100rpm and get the climb to display height out of the way, as soon as you’re high enough come back to 1,000rpm, and then you’ve got a less challenging aeroplane.”

It had been hoped to display the Camel at both of the last two Shuttleworth shows of 2017, but conditions were too windy. With all the usual provisos, it should make its public flying debut at a very appropriate occasion: the 2018 Season Premiere event on Sunday 6 May, marking the RAF’s centenary. There the fruits of so many labours will hopefully be airborne for all to see, and the exploits of one of the greatest British fighters recalled. When Sir Thomas Sopwith saw the Northern Aeroplane Workshops-built reproduction Triplane, he thought it so good that he famously declared it a ‘late-production’ example. Were the great man still alive, he would surely consider just the same to be true of this Camel.

The Camel demands notably careful handling in many areas of its flight envelope, but the rewards are there for the seasoned pilot.

”You have to be in the control loop all the time. Reputedly the only time a Camel will fly hands-off in trim is when it’s inverted”