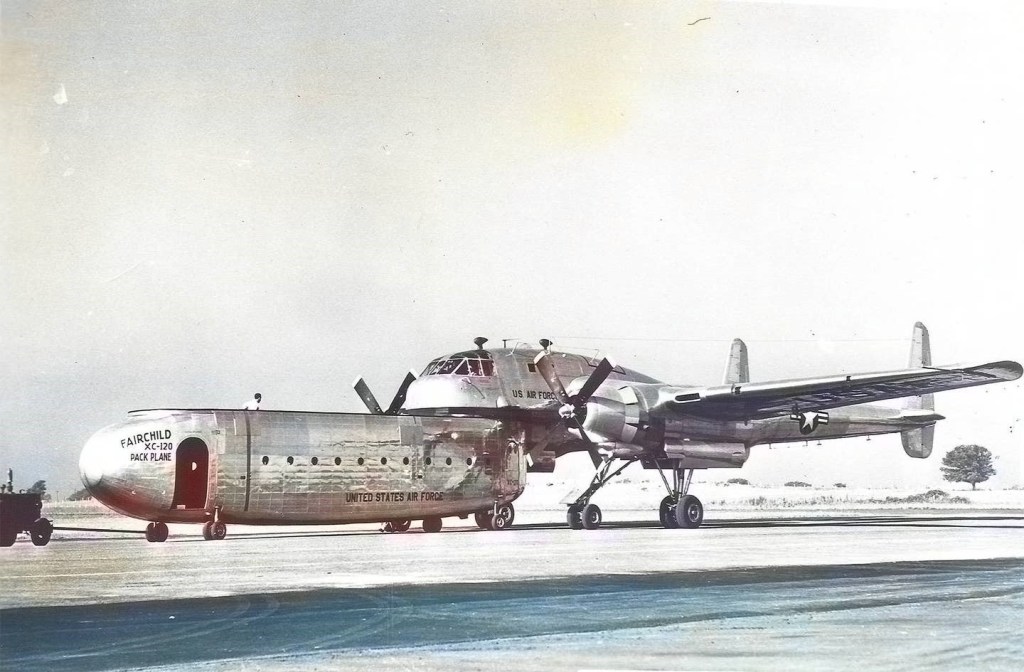

Recognizing that the loading and unloading process could become lengthy and keep aircraft on the ground for inordinately long periods of time, Fairchild engineers devised a modular cargo pod that, in theory, could be quickly and easily attached to and detached from the aircraft. The insect-like aircraft could fly with or without the cargo pod.

The conversion of one C-119B was to meet a USAF requirement for an experimental detachable-fuselage transport. C-119B wings and tail surfaces were combined with a new upper fuselage with a flat surface. A lower component with a flat upper surface, and incorporating a cargo compartment, could be mated with the Packplane.

The flight deck was in the upper component, and the type could be flown with or without pack and it was intended that various packs for different military operations would be provided.

When an aircraft arrived, crews could quickly disconnect the cargo pod it was carrying and reattach a preloaded pod in its place. This would minimize the amount of time the aircraft spent on the ground, theoretically moving more cargo over the course of a day.

The quadricycle landing gear solved the problem of loading and unloading the cargo pod but presented new problems, particularly with ground towing. Special equipment was required to keep both front wheels tracking parallel to each other when backing up. This equipment could be carried in a pod but had to be left behind when flying without a pod attached. The unique landing gear also precluded “power backs,” or utilizing reverse thrust to back the aircraft up on the ground.

Aerodynamically, it also presented some challenges. Test crews discovered insufficient lateral and directional control at low speeds. Notably, during takeoff, the aircraft’s left-turning tendency could not be overcome by full right rudder. Their solution was to utilize asymmetric power until reaching 35 knots, at which point full power could be applied. The unique landing gear also had to be retracted immediately after liftoff, as it produced large amounts of drag during the retraction sequence.

First flown on 11 August 1950, flight test reports indicate that at a power setting of 2260 BHP, the XC-120 with a pod installed cruised at 218 knots—only 14 knots slower than flight without the pod. The pod weighed approximately 9,000-10,000 pounds. Test pilots also noted that the wheel-well doors were hanging approximately one and a quarter inches open in flight during the entire test program, but this would have been the case with or without a pod attached.

With the pod attached, the absolute ceiling with one engine inoperative at 63,000 pounds (1,000 pounds below maximum takeoff weight) was only 3,300 feet. Under the same conditions, the maximum rate of climb at 2,000 feet was between 10 and 50 feet per minute.

Evaluation crews discovered that attaching or removing the pod required an “unusual” amount of time due to the slow hoist mechanism, and doing so in high or gusty winds proved challenging, requiring even more time.

In 1952, only a couple of years after the XC-120’s first flight, the program was cancelled, and the sole XC-120 was ultimately scrapped.

XC-120

Engine; 2 x Pratt & Whitney R-4360-20, 2435kW

Wingspan; 33.3 m / 109 ft 3 in

Length; 25.3 m / 83 ft 0 in

Height; 7.6 m / 24 ft 11 in

Crew; 5

Passengers; 66