Clarence Leonard “Kelly” Johnson was born in 1910, the son of Swedish immigrants, Johnson would win his first prize for aircraft design at the age of 13. By the time he was 22 years old, he was working as an engineer at Lockheed.

At 28, Kelly Johnson’s role at Lockheed would bring him to London. At the time, Britain was preparing for the onslaught to come just three years later in the Battle of Britain. The British were unconvinced that such a young man could produce an aircraft that could turn the tides of an air war, but the fruit of Kelly Johnson’s labour, dubbed the P-38 Lightning, would go on to become one of the most iconic airframes of the entire war.

It was during World War II that Kelly Johnson and fellow engineer Ben Rich first established what was to become the Lockheed Skunk Works. Today, the Skunk Works name is synonymous with some of the most advanced aircraft ever to take to the skies. But its earliest iteration was nothing more than a walled-off portion of a factory in which Johnson and his team experimented with new technologies for the P-38, developing the first 400 mile-per-hour fighter in the world for their trouble, in the XP-38.

By the end of World War II, Kelly Johnson and his team had delivered the United States its first-ever operational jet-powered fighter, the Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star. Johnson had been tasked with building an aircraft around the new Halford H.1B turbojet engine that could compete with Germany’s Messerschmitt Me 262 Schwalbe. In just an astonishing 143 days, Kelly had gone from the drawing board to delivering the first operational P-80s.

Later, Kelly’s team came through with the design and production of the C-130 Hercules. Then, in 1955, they received yet another assignment: The United States needed an aircraft that could fly so high it would avoid being shot down, or potentially even detected.

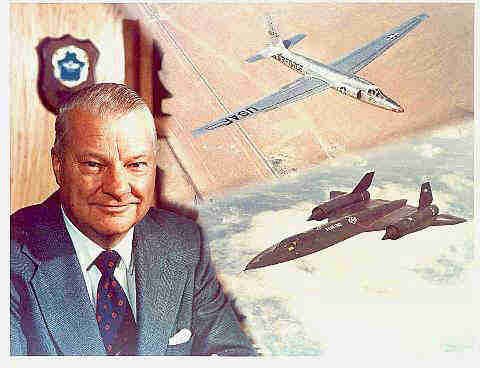

President Eisenhower wanted eyes on the Soviet nuclear program, and Johnson’s unusual aircraft design with long slender wings and no retractable landing gear seemed like it could do the job, despite its shortcomings. Johnson and his team were given a contract to design and build their high-flying spy plane. In just eight months, they delivered the U-2 Dragon Lady.

In order to test this incredible new aircraft, Kelly Johnson needed a remote airstrip, far from the prying eyes of the American public. He chose a dry lake bed in Nevada for the job. It proved particularly well suited for testing classified aircraft. Eventually, that little airstrip and accompanying hangars and office buildings would come to be known popularly as Area 51.

The U-2 may have been an immense success, but just as aviation advancements were progressing quickly, so too were air defences. In 1960, Soviet surface-to-air missiles finally managed to get a piece of a CIA operated U-2 flown by pilot Gary Powers. The aircraft was flying at 70,000 feet, higher than the Americans thought it could be spotted or targeted by Soviet radar, when it was struck by an SA-2 Guideline missile. Powers had to ride the Dragon Lady down from 70,000 feet to 30,000 feet before he could safely eject. As the secretive spy plane was plummeting to the ground, Kelly Johnson and his team at Skunk Works were already developing a platform to replace it.

It would need to not only fly higher than the U-2 but also faster — much faster, so even if it were detected, no missile could reach it. Johnson and his team designed a twin-engine aircraft with astonishing capabilities in the A-12. This then led to the operational SR-71 Blackbird — an aircraft that retained the title of the fastest operational plane in history. Lockheed’s SR-71 could sustain speeds in excess of Mach 3.2, flying at altitudes higher than 78,000 feet. During its 43 years in service, the SR-71 had over 4,000 missiles fired at it from ground assets and other aircraft. Not a single one ever found its target.

Johnson and his team needed to develop an aircraft that could defeat detection from not only enemy radar, but also other common forms of detection and targeting, like infra-red. Using the most advanced computers available at the time, Skunk Works first developed an unusual angular design they dubbed “the hopeless diamond” as it seemed unlikely that such a shape could ever produce aerodynamic lift.

Undaunted, development continued and by 1976, they had built a flyable prototype. The aircraft was called Have Blue, and it would lead to the first operational stealth aircraft ever in service to any nation, the legendary F-117 Nighthawk.

The F-117, or “stealth fighter” as it would come to be known, played a vital role in America’s combat operations over Iraq in Desert Storm and elsewhere — but this program produced more than battlefield engagements. The technology developed for the F-117 directly led to America’s premier stealth fighters of today: the F-22 Raptor and F-35 Joint Strike Fighter.

In total, Kelly Johnson had a hand in the design and development of some 40 aircraft for commercial and military purposes. He has seemingly countless awards and credits to his name for his engineering prowess. The man had a genuine affection for his work, to the degree that he turned down the presidency of Lockheed on three separate occasions to retain his role within the Skunk Works he helped to found.

Kelly’s boss at Lockheed, Hall Hibbard, once exclaimed, “The damn Swede can actually see air,” as he tried to understand how one man managed to play such a pivotal role in so many aircraft, and in turn, in how the Cold War unfolded. Finally, Kelly retired in 1975 but remained a senior advisor to Skunk Works for years thereafter. He passed away in 1990 at age 80.