When in late 1907 the Scientific American had announced a magnificent silver trophy (it featured a world globe and a replica of Langley’s ill-fated Aerodrome) as an annual award for aviation competition, it went pretty much ignored by America’s relatively small fraternity of aeronauts until AEA decided to try for it. To this goal Curtiss’ “June Bug” design was dedicated.

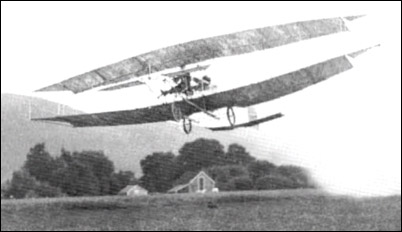

The June Bug was one of the lightest of biplanes, having a wing spread of forty-two feet and an area of 370 square feet. The wings were transversely arched, being furthest apart at the center: an arrangement which has not been continued. It had a box tail, with a steering rudder of about six square feet area, above the tail. The horizontal rudder, in front, had a surface of twenty square feet. Four triangular ailerons were used for stability. The machine had a landing frame and wheels, and weighed, in operation, 650 pounds.

Coincidentally, aviation’s “dope” also originated here when plain varnish used to water-proof fabric coverings soon cracked with use and a more flexible replacement was created by AEA from a test mixture of paraffin, turpentine, and gasoline. Over the years that basic formula was much modified and improved, but June Bug had the first coat of actual dope. How they came to choose that word, which stems from the Dutch term “doop,” for a sauce or mixture, is not known.

The June Bug was a further refinement of White Wing, was sponsored by Curtiss and was more successful with the same 40 hp lightweight V-8 engine. First flown on 21 June, it made numerous flights, including a straight run of 1042m on the seventh flight. On 4 July1908, Curtiss made a pre-arranged flight to win the first task, or ‘leg’, of the Scientific American Trophy, which called for a straightaway flight of one kilometre. After a couple of false starts, he won this with ease by flying 1.6km at a speed of 62.76km/h in 1 minute 42.5 seconds.

The machine made several test flights from 450 to 3,420 feet, which Scientific American reported as the longest flights ever “publicly accomplished by a heavier-than-air flying machine in America at any accessible place.” (Hammondsport was likely more “accessible” to the magazine than was Huffman Prairie, Ohio, whence the Wrights had made flights in 1905 up to 24 miles over the heads of any public that cared to look up!)

However, on his eighth venture into the sky, and in the USA’s first officially-recorded “public flight,” Curtiss travelled 6,000 feet in 01m:42s at 39 mph to win the trophy on July 4, 1908. Yet, to dull the flush of victory, this event precipitated a letter from the Wright Brothers warning of patent infringement on their control system. Despite this legal snarl, AEA managed to get the aileron system patented in 1911, which was later transferred to Curtiss, and which would eventually lead to a full-blown court battle between the brothers and Curtiss that would drag on for years until the Wrights finally won.

In 1909 Curtiss exhibited intricate curved flights at Mineola, and circled Governor’s Island in New York harbor. In 1910 he made his famous flight from Albany to New York, stopping en route, as prearranged. At Atlantic City he flew fifty miles over salt water. A flight of seventy miles over Lake Erie was accomplished in September of the same year, the return trip being made the following day.

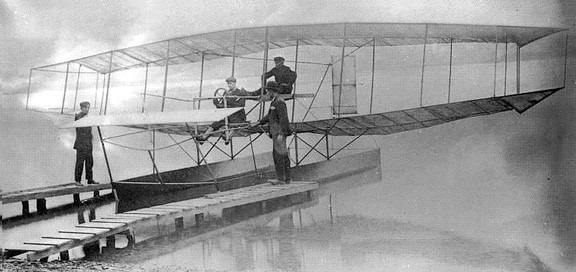

Curtiss fitted twin pontoons to his June Bug, renamed it Loon, and tested it in June 1909. It attained a surface speed of 27mph would not leave the water. During subsequent attempts it went out of control, sank in the shallows, and became frozen in the ice.

On January 26, 1911, Curtiss repeatedly ascended and descended, with the aid of hydroplanes, in San Diego Bay, California.

The June Bug was used by Curtiss for a total of 32 flights. It then crashed on 2 January 1909 and went into retirement.

Wingspan: 12.95 m / 42 ft 6 in

Wing area: 34.37 sq.m / 369.96 sq ft

Length: 8.4m / 27ft 6in

Take-off weight: 279 kg / 615 lb